Out of Sight

Elmore Leonard, Mr. Cool

Here’s a post about this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics. We choose the films almost at random: one of us will watch (or rewatch) something and text the other guy. We then record without any previous conversation, recreating the enthusiastic conversations people have in the cars on the way home from the theater. We also take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over 250 and you can find them all here. Spoilers always abound.

In 1988 I wrote to Elmore Leonard, care of his publisher, telling him how much I enjoyed his books. I had just finished his latest, Freaky Deaky, and asked if he ever did the dance after which he named the book. I mailed it and forgot about it. A few months later, I received this reply:

Sometimes the people whose work we admire really are as cool as we hope they are. Even his handwriting fit the impression I had formed of him.

Leonard began as a writer of westerns; when that market dried up, he moved to crime. But there was really no difference in the books: his characters left Santa Fe for Detroit, but they still acted and spoke the same way, stealing counterfeit cash instead of cattle. I remember people wondering before Leonard’s Cuba Libre was published in 1998 if he was growing tired of crime and moving into a new genre of historical fiction—but, thankfully, no: the book takes place in 1898 before the Spanish-American War, but the characters are all gunrunners, bank robbers, and charming talkers. When the Maine explodes, Leonard uses it as a plot device, not an occasion to ponder American interventionism. Just as Orson Scott Card settled the “What’s the difference between science fiction and fantasy” question by declaring, “Science fiction has rivets; fantasy has trees,” a reader can think of Leonard’s westerns and crime novels with the same model: some have cows and some have cars, but there’s much more crossover than space between them.

I used the word “cool” earlier to describe Elmore Leonard and that wasn’t authorial laziness. That word has been used for centuries to describe a person not overtaken by emotions—the OED cites its appearance in Beowulf—but here I mean it as it was first used to describe American jazz: “restrained or relaxed in style.” The OED illustrates this definition with a passage from Leonard Feathers’ 1956 Encyclopedia of Jazz: “Cool jazz to most musicians and students denotes the understated, behind-the-beat style typified by the arrangements and soloists on the Davis records.” This is exactly what makes Leonard’s work so enjoyable: the appearance of ease, the illusion that writing dialogue comes naturally, the relaxed pose of his protagonists, who are never dirty cops who occasionally do the right thing or undercover operatives infiltrating the mob or epic tales of law and order filled with operatic violence. His heroes love understatement, try to avoid trouble, and always end up earning the reader’s favor and the plot’s rewards. John Russel in Hombre (1961), Vince Majestyk in Mr. Majestyk (1974), Joe LaBrava in LaBrava (1984), Jackie Burke in Rum Punch (1992), Dennis Lenahan in Tishomingo Blues (2002), and, naturally, Chili Palmer in Be Cool (1999) are some of the dozens examples of the Leonard Lead, a distant relative of even cooler ancestors like Will Kane and Sam Spade.

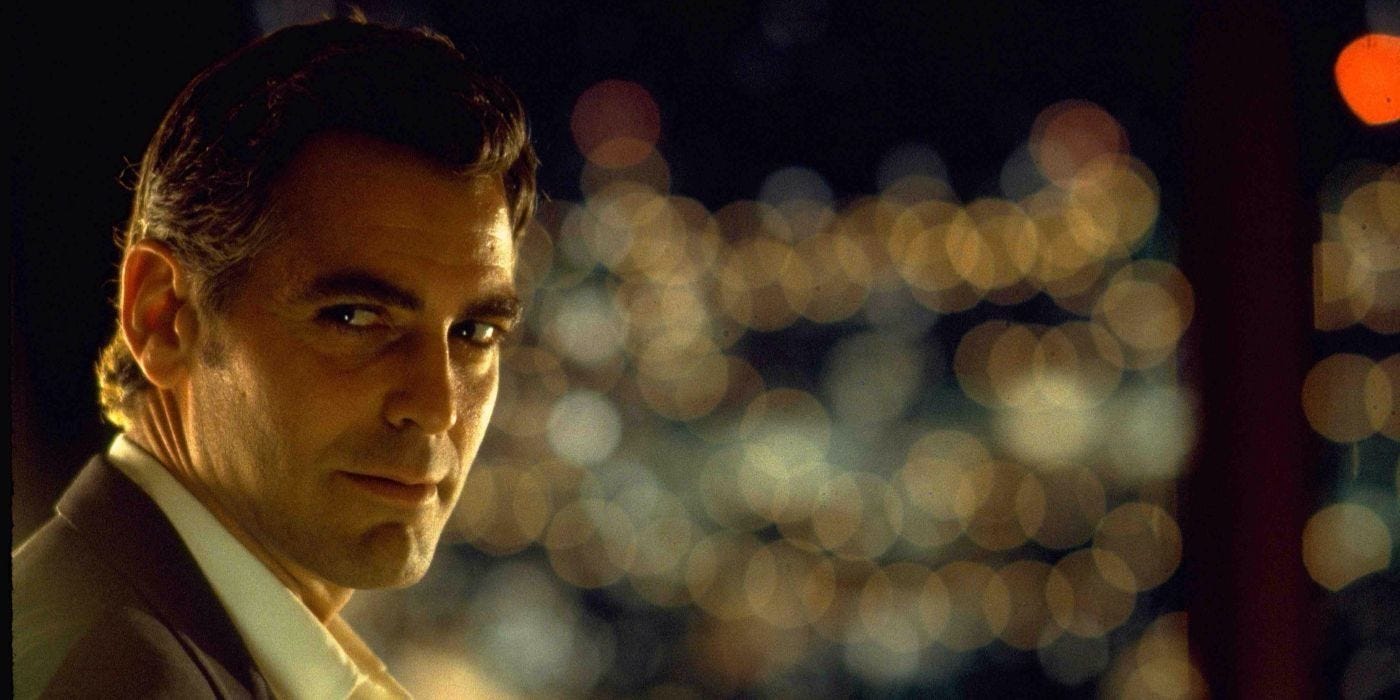

They all, to some degree, act like George Clooney and Jennifer Lopez do in Out of Sight.

The tension (and fun) of the film is that Lopez, a U.S. Marshall, is drawn to Clooney, a bank robber. But that’s not the only romance in play: Soderbergh is as enamored of Clooney as Hitchcock was of Cary Grant and does everything he can to make the viewer feel this way as well. From his flicking the Zippo to the way he doesn’t look up from his book in the prison library when he tells the dangerous Don Cheadle that he’s conducting the dumbest shakedown in the history of shakedowns, to the way he diffuses a tense moment by saying, “Just like back in the yard, isn’t it,” Clooney romances the viewer as much as he does his co-star. The romance works because Clooney’s character (who even has a cool name: Jack Foley) is one of Leonard’s good-bad-guys. Yes, he’s a bank robber, and yes, he escaped prison, but he’s not one of the bad-bad-guys like Snoop or Whiteboy Bob. He’s so cool that he never even uses a gun to rob the banks—a true charm offensive.

Watching Out of Sight makes us feel like we’re being carried along in a very natural stream of cool. Soderbergh allows us to keep many different elements in our heads at once and get a small dose of dopamine when we realize how they connect. We see Clooney leave a building in the opening scene, tossing away his necktie in anger and then forget about it until we later see what led to it and make the connection. We watch Clooney and Lopez have a drink and dance around each other like two moths and two flames while we simultaneously see the result of their flirtation. (We have sat through so many gratuitous “love scenes” that do nothing for their films, but here, the cutting away makes the flirtation more economical and interesting.) The film’s manipulation of time seems effortless, but if you drew it on paper it would look only a bit less complex than the ones for Primer or Tenet. We catch up, for a second, with the man behind the curtain, as we do when we read Dante or Nabokov and feel, well, cool for doing so. It’s like we’re finally sitting at the right lunch table.

Out of Sight does what Netflix and other platforms try to do all the time: throw a bunch of stars together in an effort to increase the quality of the “content.” But we can sense the half-assedness of these movies when we watch Out of Sight, which has a long list of talent in addition to Clooney and Lopez: Albert Brooks, Don Cheadle, Steve Zahn, Luis Guzmán, Catherine Keener, Dennis Farina, and Ving Rhames, who improves every movie in which he appears.

Out of Sight is the second-best adaptation of an Elmore Leonard novel, the best being Jackie Brown, which also got Leonard’s vote as the best of them. Tarantino's film isn’t as light as Soderbergh’s, but, like Out of Sight, it has two cool customers (Pam Greer and Robert Forster) as good-bad-guys, raising their already high levels of cool as they outsmart the bad-bad-guys. Leonard’s Leads have been played by Pam Greer, Jennifer Lopez, George Clooney, Charles Bronson, Paul Newman, Roy Scheider, Timothy Olyphant, John Travolta, and the master of that “restrained and relaxed” style mentioned in the OED, Burt Reynolds.

If we could put all of them in the same room, the cool quotient would be immeasurable.

Listen on the player above, on the New Books Network, or wherever you get podcasts.

Great piece, Daniel. And that letter, man. Wow, what a gift!