Concert Venues: Bad as Movie Theaters?

Bob Dylan and the Madness of Crowds

In February, I posted “The Biggest Lie About the Movies” and argued that the often-described “communal experience” of seeing a film in the dark, surrounded by strangers, was, at best incredibly rare and at worst romantic rot, something movie lovers say in defiance of the stubborn facts seeing movies in America today, where people text, talk, and try to soothe crying infants. That post and its follow up, “If I Ran a Movie Theatre,” gave me my fifteen minutes of Substack fame. More people responded to these than to my posts about Henry James or Canadian novelists. It seemed to be a universal complaint.

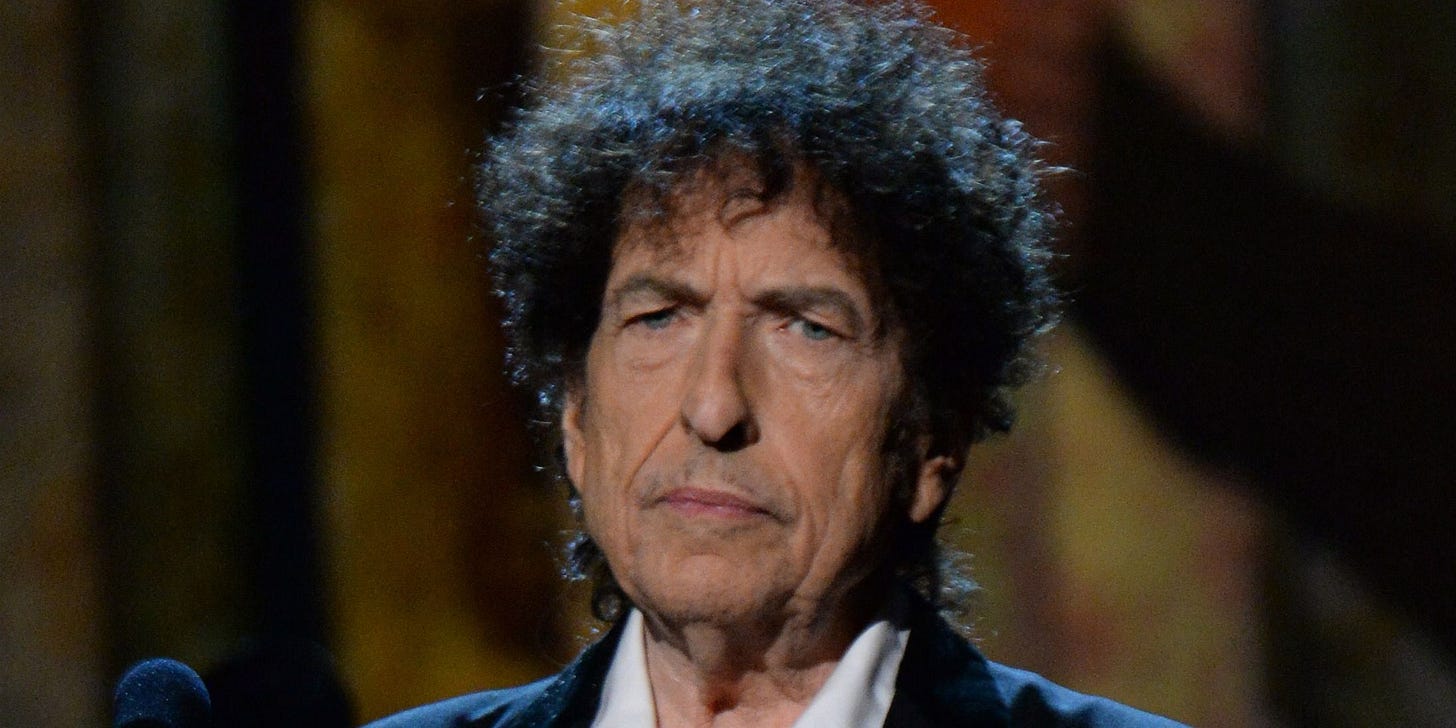

Fast forward to last Friday, when I went to see Bob Dylan as part of the Outlaw Festival. This was a sit-down crowd, to be sure. The average age, if I had to guess, was midfifties, although there were younger people there, perhaps pulled in by A Complete Unknown and thinking they would see a distinguished gray version of Timothee Chalamet singing, “Highway 61 Revisited.” They had a big surprise in store: Bob played the song, but did so from what may as well have been an underground bunker.

And what I saw and heard there explained why: if the darkness of a movie theater lessens many people’s common courtesy, the darkness of a concert venue obliterates it.

Because of New Jersey’s number-one crop—traffic—we arrived in the middle of Sheryl Crow’s set. When she played “All I Wanna Do,” a woman who resembled John Goodman and dressed like Robert De Niro in the opening of Raging Bull (plus a faux-spray-painted straw cowboy hat) was dancing and grooving and shaking her hips like the belly dancer in the opening of Hawaii Five-O, screaming “YEAH!” every few minutes and high-fiving strangers. She pointed to another woman and yelled, over the music, “THIS IS HER FIRST CONCERT!” I thought to myself that it was probably her first beer. When Sheryl Crow reached the chorus of “If It Makes You Happy,” I wanted to use the old joke on the dancing woman:

“Who sings this?”

“Sheryl Crow.”

“Let’s keep it that way.”

After she ended with “Every Day is a Winding Road,” the house lights came on and everybody milled about, waiting for Bob. I pointed to the piano and thought I’d have a good sightline; I even had my $15 binoculars that I bought just for this occasion. Of course, I could watch the big screens, but that didn’t seem to be the same thing. I knew from setlist.fm that he would go on at about 8:00, and at 7:50 or so, the lights went down and the band walked onstage. The lights stayed low, so I assumed they were getting into their spots; I thought we’d also hear the usual, “Ladies and gentlemen, Columbia recording artist … Bob Dylan!” as on other nights of the Never-Ending Tour. But there was no announcement and the lights on the stage stayed low. The brightest lights were those atop the piano.

Those lights were like three candelabra or miniature Christmas trees, placed there deliberately so that you couldn’t see Dylan’s face behind them. When they began “Masters of War,” the opening number, I realized that the screens weren’t on. People were confused, but I shrugged and tried to listen. All my binoculars showed me were the outlines of the band members: when I pointed them at the piano, it was like looking at three small supernovae. Here’s a video (posted by John Mauceri) of Dylan a week earlier in Hartford, so you’ll see what I mean more than you’ll see Bob:

After the first song, I said to my son, “You know why those screens aren’t on? Vanity.”

But then I thought back to the last time I saw Bob in 2023: we were indoors and had to use Yondr pouches for our phones. This was all new to me: as we waited to enter the venue, we showed our on-phone tickets to an attendant, who wrote our seat locations on a slip of paper, handed us the paper, and then had us put our phones in canvas pouches, sealed with magnets we couldn’t open until we deactivated them on the way out. It was strange and wonderful: imagine a whole concert hall with three thousand people not on their phones. As we sat there before the show, we remarked on how strange it felt: even with people you love, you check your phone once in a while if it dings or just to “look something up.” When Bob took the stage, nobody, save a few people who must have had burners, took out their phones. We heard Bob but also saw him and on the way out I said that it’s too bad they don’t have these pouches in movie theaters or restaurants.

I was wrong about Bob’s vanity, at least as the cause of the no-screens and invisibility. According to Rolling Stone and scores of fans, he’s been wearing a black hoodie pulled tight and using the strategically placed lights to make people listen to the music instead of taking photos the whole time. He finds the phones as annoying as I do. And since he can’t use Yondr pouches as part of the Outlaw Festival, he did the next best thing. He couldn’t get rid of the phones, but he could give them less to record.

Dylan kept playing, but the crowd kept talking and pontificating. In the middle of the fifth song, “To Ramona,” two guys a few rows in front of me started pointing at each other, yelling, and squaring off. The women around them started yelling, “Security! Security!” Some shined their flashlights at the guys; one was filming them; people behind me started yelling for them to shut up and sit down. Eventually, a security guy who looked like Chief Wiggum’s body double came over and got the instigator to move along. He did, but then his sidekick (as you could tell by the body language), stood there and tried to drunkenly apologize to the women. More people yelled. Bob continued singing; when he got to the line about his words turning into a meaningless ring, it was an accurate description of how he was being received.

Without a potential fistfight to captivate them, three women in front of me began speculating, in voices as loud as mine after three mojitos, about what was happening onstage. One said that there was no way to tell if Dylan was even there: “For all we know, it’s a recording!” A second affirmed this and nodded like a bird, over and over, saying, “You know, I thought his voice sounded different in different songs!” This Bob-on-the-grassy-knoll idea is exactly what Andy Greene mentions in his Rolling Stone piece:

It’s not an impostor. That’s the real Bob Dylan. He’s just really, really tired of people watching the show through their cellphones as opposed to their own eyes. And why shouldn’t he be? Phones have made concerts almost unbearable at times.

Yet as they complained, one of them occasionally took out her phone and tried to take short videos of the stage and the musician she was complaining she couldn’t see. Half of the time, she was, in true Boomer fashion, actually making the recording stop instead of start, but this didn’t deter her from holding it up like a parent at a kid’s orchestra concert as they lumbered through “Hot Cross Buns.” I closed my eyes and concentrated on the music.

The arrangements Dylan uses when playing live are often different from those on his records, so when he began “Desolation Row” and “All Along the Watchtower,” I was caught off guard in the best way. By now the three weird sisters were still yapping but I couldn’t really hear them. I was just irritated that they were a hundred yards away from Bob Dylan, singing “Watchtower,” yet not listening—and that they kept snapping photos. Why? What were they going to do with them? You can’t really see anything—it’s like a smudge of light, but Bob Dylan was, like, behind it. I knew he was going to play “Blind Willie McTell” and prayed that one of them would go to the bathroom. She did, which broke up the troika, and I was able to enjoy that and “Soon After Midnight.” At the end of the closer, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” the band bowed and I grabbed some binoculars quickly enough to see the shadow of Bob as he walked offstage.

The lights came up and we waited for Willie, who assembled with his band behind a screen, maybe so the audience didn’t have to see the slow walk-on of the 92 year-old legend. “Are you wearing socks?” one of the women in front of me asked her friends. “Because Willie is going to knock them off.” The screen lifted to reveal Willie, perched on a stool, singing his standard opener “Whisky River.” He sounded pretty good—although it was at this time I learned that the sock-knocker also knew how to make a piercing whistle with her pinkies, as if she were summoning a pony to wait for her under a second-floor window. She did this about six hundred times. Everybody was sitting down, but when three other women stood up to dance to “Stay a Little Longer,” people behind them started yelling. These three were the only ones standing in the whole section. A guy behind them in my row asked if he and his presumed dad could jump into the seats next to us; we said sure. The dad had a cap that read “Vietnam Veteran”; the guy had served in Nam and now just wanted to enjoy “Bloody Mary Morning” in relative peace. When Willie began playing his slow acoustic songs and began “Crazy,” one of the three in front of me nodded and said to her friends, “You know that he wrote this song! Patsy Cline sang it but Willie wrote it! He actually wrote this song.” She repeated this fact about the song instead of listening to it, like someone who stands under “The Creation of Adam” reading the guidebook but never looking up at the painting. This fact was also delivered like some great profundity, Charles Foster Kane’s last word, instead of something that everybody in the universe already knows. If she ever sees Bruce and he plays “Jersey Girl,” she’ll be ready to reveal that it was written by Tom Waits.

I could go on, but you get the idea. While I had a great time seeing Nick Lowe at a park in Pennsylvania, many big concerts have become as bad as movie theaters; probably worse, since the people here had been drinking $15 beers since early afternoon. I don’t think we should all act like the crowd around Bugs Bunny when he walks onto the symphony stage—

—but the degree of narcissism and disregard for other people is incredible. We're told all their time about the power of live music, and that's true. But here it seems that Bob was misplaced in a tour among people who didn’t want to buy what he was selling. Or perhaps they could have bought it if they had shut up enough to listen. Even Bob didn’t want to deal with them. People used to care, but things have changed.

As he sang in “Idiot Wind,” people see him all the time and they just can’t remember how to act.

Perfect last line 👌

Great piece! Good on Bob for continuing to challenge his audience. I hate it when people talk all the way through concerts.