Competing with Idiots

Here’s a telegram that I’ve projected onto a screen and asked students to close-read:

Knowing nothing about Herman Mackiewicz, Ben Hecht, or telegraphic style, my students were able to accurately describe the sender, what he assumed about the recipient, and how he regarded other people. The imitation job offer, the use of “peanuts,” and the final sentence all point to the sender’s personality and facility with words. One simply knows that he did not make multiple drafts of this, but rattled it off.

You, of course, know that Herman J. Mankiewicz co-wrote Citizen Kane (originally titled American) and was the older brother of Joseph Mankiewicz, who directed a number of films, such as The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, A Letter to Three Wives, and the stunning All About Eve. And yes, he also directed Cleopatra, which is not nearly as bad as billed. (See the post on Killing John Wayne for my remarks about it.)

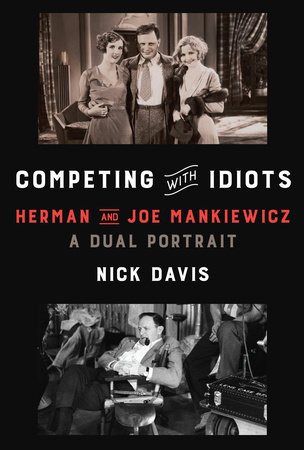

What you may not know is that Nick Davis, Herman’s grandson and Joe’s grand-nephew, has written an incredible dual biography. Competing With Idiots (2021) is a portrait of the brothers as they grow up under the stern hand of their father, Franz, set out for Hollywood, make a number of impressive films, and chase the bitch-goddess Success. It does everything a great biography should do and does it with style, intelligence, and enthusiasm.

Other people have written accounts of the Brothers Mankiewicz; what sets Davis’s book apart is that he has written himself into it and allows his own struggles in understanding these men to illustrate the degree to which we are all, in some ways, strangers to each other. Born in 1965 to Johanna Davis, Herman’s daughter, Nick only knew his maternal grandfather and great-uncle through family lore. Over and over he heard two characterizations that he accepted without question: Herman was the funniest man who ever lived and had co-written the greatest film ever made and Joe was a lesser talent who directed the worst film ever made. Even as a young man, Davis would think, “But what about All About Eve? Didn’t he also make some terrific films?” but was never able to learn more. Questions about Joe resulted in the other person changing the subject.

The book opens with the twenty-three year-old Davis returning, with his father, from an event at the French consulate at which Joe was awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur for reasons Davis couldn’t understand: didn’t he make, at best, two or three good movies? Joe greeted Davis, whom he barely knew, warmly, introduced him to Claudette Colbert, and seemed “lovely and warm and real.” Why had Joe remained, if not an outcast, on the outskirts? His father then tells him a story about Joe that haunts him and propels him into his quest to learn more about his great-uncle and older brother.

When I asked Davis about his decision to begin the book with, “It’s only when you stop knowing everything that you can start to know anything at all,” he talked about the Official Mankiewicz Party Line on Herman and Joe and added, “It was only when I stopped knowing ‘everything’ about these two guys and started to admit, ‘Wait a minute, I don't know anything about either of them, really–it’s got to be more complicated than this,’ that I stayed to make progress.” This wasn’t easy, since one irony of the family is that, while they made their living through the skillful use of language, “almost nothing of any real importance got discussed in a serious way.” Competing with Idiots is a record of that progress and how Davis was able to create this portrait of his famous ancestors.

It’s a portrait–not a photograph or the last word on these two men–because Davis knows that he’s offering his impressions of the subjects. Just like Jerry Thompson trying to piece together the fragments of Charles Foster Kane into a coherent understanding of the man, Davis pieces together what he’s learned about Herman and Joe. Davis calls Charles Foster Kane “virtually unknowable”; late in the book, Joe remarks, “I don’t think anybody exists as one pure note of music, or one color–people are fragmented.” That’s an idea taken right from Citizen Kane.

In The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde puts one of his many ideas about art into the mouth of one of his characters:

Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter. The sitter is merely the accident, the occasion. It is not he who is revealed by the painter; it is rather the painter who, on the coloured canvas, reveals himself.

What Davis reveals about himself in his dual portrait is how he responded to learning more about Herman, Joe, and his own place in the Mankiewicz story. He also learns about the mystery of talent: how it’s unearned, courted, and sometimes wasted.

After I read it in March of 2022, I walked around like an end–of-days preacher, urging everyone I knew to read it. On the widest of chances, I emailed Davis and asked him to come onto Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics to talk about the book and help us celebrate our 150th episode on Citizen Kane. He responded the same day, saying he had checked out the show and was glad to report that we were “not crackpots.”

I reread the book, Nick came on the show, and we had a great time. I was amazed that we were going to talk about Kane with a Mankiewicz. Maybe I wasn’t a teenybopper screaming for The Beatles, but I admit I was close–not only because of who Nick is but, more importantly, because I admire his book as much as I do. He went along with the structure we use for the show, didn’t talk over us, and responded to what we said about the film. It was a genuine conversation and a highlight of my reading life. You can hear that episode here. When I began hosting on the New Books Network, I asked Nick for another, longer interview, which he graciously gave. You can hear that interview here.

Don’t let this get around.