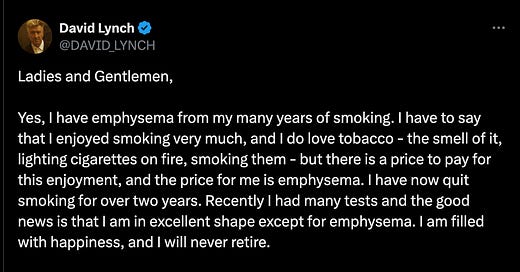

On the afternoon of August 5, 2024, David Lynch posted this to X:

Any teacher of writing can put this on a screen in front of a classroom and ask students to close-read it. I am not being facetious. If every piece of writing has a purpose, how does this piece of writing achieve its author’s goals? How does Lynch announce a potential death sentence to strangers and admirers? It’s the same challenge that Ronald Reagan faced in 1994: to address rumors about his health and present himself to the public with dignity and sincerity.

Lynch has clearly read or absorbed the most important piece of advice in Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style:

Omit needless words. Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

I’ve urged this upon my students for years, having them reduce a piece of their writing by 20%—and then by another seemingly impossible 10%. It always works and illustrates the truth of the rule: the reduced versions are, almost always, superior to the longer ones. Every book we read and movie we see was longer before it reached us—and how many deleted scenes from a movie would you actually restore after seeing them? (Almost every “Director’s Cut,” save this one, makes me side with the producers.) Too many people think that “good writing” has to be verbose, which is where people get the mistaken assumption that the novel is a form superior to the short story and longer films are somehow more “serious” than shorter ones. (Films may not actually be longer than in the past, but they feel longer than ever before.)

William Carlos Williams was able to capture the essence of temptation—using another forbidden fruit—in twenty-eight perfectly arranged words. In his announcement, Lynch tells the straight story of his diagnosis in a hundred-and-seven without resorting to being maudlin or—worse—lapsing into cliches about “journeys,” “challenges,” or “community.”

The salutation would be an affectation elsewhere, as when a boss uses the phrase to address the staff before a meeting. Here, however, it works because Lynch is in show business; it also comes across as light, a tone sustained throughout the tweet. (Beginning with, “To my fans” would seem self-serving; “Dear Twitter” would be impersonal; no salutation at all would be too abrupt.) The opening “Yes” is a definitive means to address the elephant in the chat room—the rumors of his impending death are not exaggerated—but what follows is an inversion of expectation: his statement that he “enjoyed smoking very much” and reminders of the pleasures he found in the very act that led to his illness is a suggestion that he doesn’t resent or blame the elephant for arriving. It’s the opposite of the famous Yul Brynner TV-ad of 1986 (seen below). Instead of a warning, we get an older man’s appreciation that everything has what economists call an opportunity cost and that the bill for the sensual pleasures he found in tobacco (the smell, the lighting cigarettes) has come due.

The next sentence is straight and declarative, anticipating the readers who wonder if he will continue his habit, despite the diagnosis. As with the “Yes,” he wants to state the facts. What follows is surely the oddest sentence any of us will read today: the “many tests” show the “good news” that he is in “excellent shape except for emphysema.” This may ring of, “Other than that, Mrs. Lincoln, how did you like the play?” But it strikes me as his version of what Dylan Thomas wanted for his father: while he doesn’t rage against the dying of the light, he doesn’t whine, either, at least in public. The two clauses in the last sentence are affirming—and, again, while we don’t know what has occurred in his heart from the diagnosis until this moment, we do get the sense that he has no reason to lie.

The closing could easily be Strunked to “I appreciate your concern,” but deleting those first seven words would take away the conversational tone and make the message sound like ChatGPT. “Love, David” does the same: if it were simply signed “David Lynch,” it would read more like a press release than the personal note it’s meant to imitate.

The whole performance here suits the perception of Lynch that many have had of him through his films, interviews, and wonderful memoir. He’s a director whose portrayals of almost unfathomable and irrational darkness are matched by one of the most family-friendly and affirming G-rated films ever made and a genuine joy in giving daily weather reports or sharing the most mundane DIY projects and somehow drawing in an audience. Lynch can no longer walk more than a few steps and cannot leave his house, so who knows how much of the tweet is him putting on a brave face or what kind of thoughts run through his head as he looks out his window? Is he always as equanimous as he seems here, talking of costs and sensual pleasures?

Samuel Johnson would roll his eyes at all of this and say, “Sir, Lynch may post whatever he likes, but confront him at the time of his passing and see if he retains his equanimity.” We can’t go as deeply into Lynch’s head as we can into those of his creations, but we can take him at his word about being touched by the concern of many people and responding in a way as down-to-earth as his X profile: “Filmmaker. Born Missoula, MT. Eagle Scout.”