David Lynch's Best

The Straight Story

This essay accompanies this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics, a podcast that often breaks the promise of its title but never wastes the listener’s time. The post and the podcast complement each other; the post isn’t a transcript of the podcast, so please give it a listen. We take requests; leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over three hundred episodes that you can find on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts. There’s also a player at the end of this post. Check out the back catalogue for episodes on your favorite films—or give us some you’d like us to cover. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts and consider leaving a review on your platform of choice. Thanks.

The Straight Story is David Lynch’s best film.

It’s not his most inventive, revolutionary, or “Lynchian” (although Lynch himself claims to know nothing about that term). But it is the one in which he holds the mirror up to nature more directly than he does anywhere else.

One way to think about the greatness of The Straight Story is by way of analogy, comparing David Lynch to another groundbreaking artist, James Joyce. Joyce’s four major works—Dubliners, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses, and Finnegans Wake—increase in formal complexity: middle schoolers could read “Evelyne” but tenured professors cry uncle after ten pages of the Wake. Everybody, however, admires Ulysses. And well they should: there’s nothing like it under the sun. Truly bottomless, it is genuinely “about the novel,” a phrase undergraduates used to love writing on exams when they couldn’t think of anything else to say (and were still assigned challenging reading). What begins as a traditional novel, with stately, plump Buck Mulligan about to shave, becomes one in which a chapter is interrupted by newspaper headlines, another mimics the history of the English language, another is a phantasmagoric play, others parody any number of literary styles, and the last replicates a character’s consciousness in eight punctuated sentences over sixty pages. If a novel were ever a tour de force, it’s this one, which is why everybody learns to praise it even if they haven’t read it.

One effect of Joyce’s invention is that he’s always there: the style may sometimes challenge a reader, but it’s also difficult to read Ulysses and lose oneself in the action. Nobody today can pick up Ulysses without some preconceptions, but imagine those first readers in 1922: after lulling them into thinking the book is a tale of an Irish Everyman, Joyce begins breaking the novelistic fourth wall so often that readers must have looked back on the opening chapters as if they were part of another book. Like Moby-Dick, which works in a similar way (before returning to its traditional roots at the end), it’s one of the great bait-and-switch moves in literature. Joyce knew this and delighted in it, remarking, “I've put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that is the only way of ensuring one’s immortality.” He shared, with translator Stuart Gilbert, his own ideas about each of the novel’s eighteen chapters and it took Gilbert an entire book of his own—one of the first pieces of Joycean scholarship—to explain Joyce’s themes and techniques. Joyce meant to wrestle with its readers not for the sake of being deliberately obscure (like a seventh-grader’s free verse) but because he thought human nature demanded a new way of being explored.

Some critics have asserted (and complained) that modernist writers were “difficult on purpose,” that Leopold Bloom, the hero of Ulysses, could never read it. This strikes me as backwards. Joyce’s work is no more deliberately difficult than quantum physics: the difficulty lies in the complexity of what’s being examined.

As for Finnegans Wake, I stand defeated. Anthony Burgess can talk all he likes about its knee-slapping humor—and his online Guinness-laced explanation is incredible—but I confess to feeling like Homer Simpson watching A Prairie Home Companion when I have tried to read it.

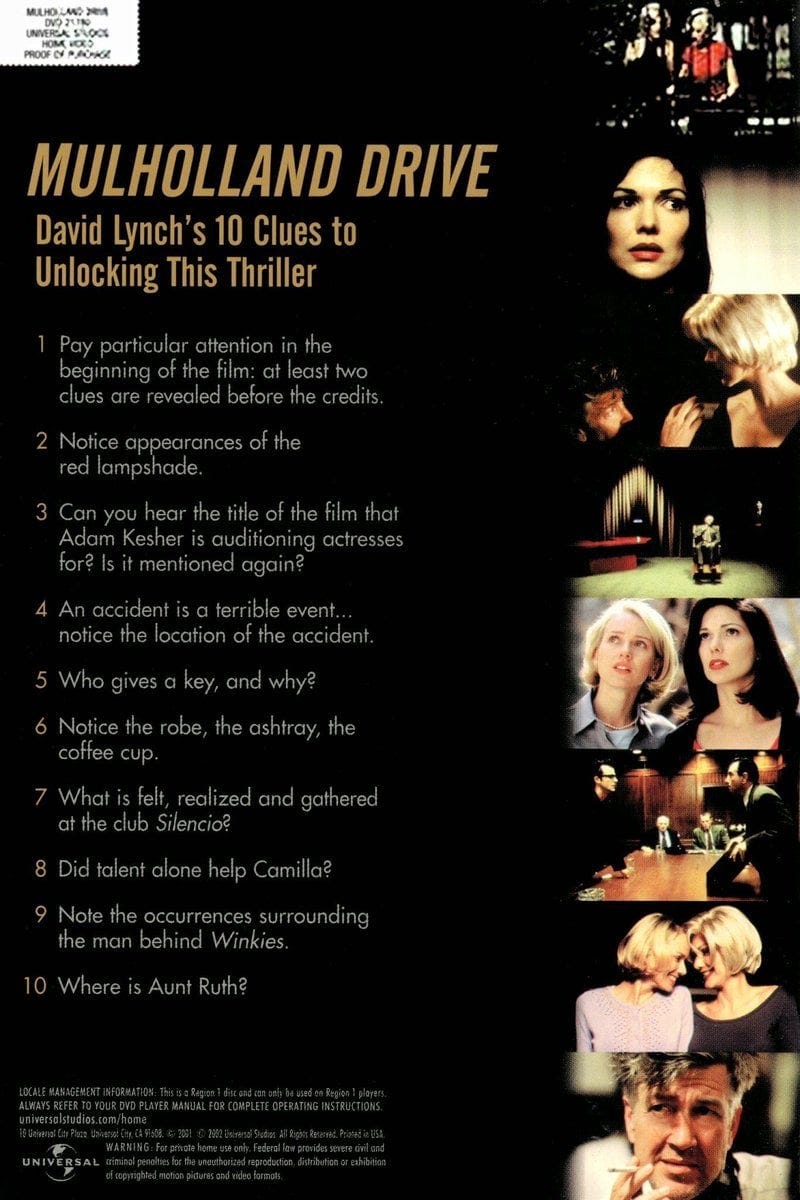

Much of Lynch’s work is like Ulysses. When we freshman film folks first saw Blue Velvet, we were mesmerized by the camera moving into the ear, the fighting beetles, Dennis Hopper, and the clues that we loved unpacking to determine what actually happened: someone would say, “Hey—Frank Booth lives on Lincoln Avenue!” and we were off to the races. On Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics, we call these details “red arrows,” named so because of the graphics used by enthusiasts in their YouTube videos in which they show viewers everything they missed the first time through a movie. Twin Peaks, Mulholland Drive and Lost Highway all have similar Easter eggs and invite the same kind of red arrows seen all over YouTube. Lynch loves this kind of thing: when Mulholland Drive was released on DVD, the package included a card entitled, “David Lynch’s 10 Clues to Unlocking This Thriller”—this may be the first time in which a movie came with its own Cliffs Notes. Like Joyce, Lynch delights in enigmas and puzzles: fans will recall the wonderful moment in the middle of the first season of Twin Peaks when their question “Who Killed Laura Palmer?” was replaced by, “How Much Further Is He Going to Push This?” He pushed for his whole career: from the time we first see Henry Spencer’s face superimposed on the moon in Eraserhead to the crazy dance party that ends Inland Empire, we are aware of Lynch’s presence.

If Mulholland Drive is Lynch’s Ulysses and Inland Empire is his Finnegans Wake, The Straight Story is his Portrait of An Artist. Joyce’s 1916 novel about the physical and artistic growth of Stephen Dedalus doesn’t have the degree of invention seen in Ulysses, but its accessibility often makes it more moving than its sequel. And it’s no slouch in terms of stylistic inventiveness: the language of each of its five chapters mimics the artistic development of its hero, beginning with its opening:

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo ...

His father told him that story: his father looked at him through a glass: he had a hairy face.

The language and what it describes are as close to Stephen’s sensibility as they can be; Joyce does this in every sentence. When Stephen later becomes a lovestruck teenager, he sees Eileen Vance, a girl with whom he is smitten, on the way back from a party:

She had thrown a shawl about her and, as they went together towards the tram, sprays of her fresh warm breath flew gaily above her cowled head and her shoes tapped blithely on the glassy road.

It was the last tram. The lank brown horses knew it and shook their bells to the clear night in admonition. The conductor talked with the driver, both nodding often in the green light of the lamp. On the empty seats of the tram were scattered a few coloured tickets. No sound of footsteps came up or down the road. No sound broke the peace of the night save when the lank brown horses rubbed their noses together and shook their bells.

Surely this is wonderful writing: phrases and images that would seem overwrought or cliched to an adult perfectly mirror Stephen’s experience and remind readers of times in their own lives when the magic of a crush seemed to be echoed by the most mundane events. The writing here is not “direct,” since everything is filtered through Stephen’s development, but the technique of telling the story as Stephen experiences it makes those experiences more immediate and often more moving than some of those described in Ulysses:

You move a motion? Steve boy, you’re going it some. More bluggy drunkables? Will immensely splendiferous stander permit one stooder of most extreme poverty and one largesize grandacious thirst to terminate one expensive inaugurated libation? Give’s a breather. Landlord, landlord, have you good wine, staboo? Hoots, mon, a wee drap to pree. Cut and come again. Right. Boniface! Absinthe the lot. Nos omnes biberimus viridum toxicum diabolus capiat posterioria nostria. Closingtime, gents. Eh?

Like Robinson Crusoe, a book Joyce adored, Portrait captures a complete sensibility on paper without calling too much attention to its creator. The power of Hank Williams lies in the directness of his melodies, lyrics, and singing; the appeal of Frank Zappa’s instrumentals is their complexity and inventiveness. But Zappa also illustrates the risks artists run when their work becomes overly complex, increasing the adoration of the already-converted but simultaneously alienating the newbies.

The Straight Story has an honesty and directness not found anywhere else in Lynch. (The Elephant Man is a close second.) The film that doesn’t rely on any observable technique to achieve its effects, which is appropriate for a tale of Emersonian self-reliance. Alvin Straight has a name that suits him and applying a form like that of Wild at Heart to his story would make his journey ironic. But Alvin Straight, a man who has harbored a grudge against his brother for decades and now fears that they will not reconcile before one of them dies—cannot afford the luxury of irony. At Alvin’s age, reality is not a collection of red arrows, but one big arrow pointing to the end and he knows he needs to see his brother before he gets there.

The Straight Story is one perfectly-executed, gorgeous scene after another. When I first purchased the DVD and saw that there were no chapters because Lynch (as he noted on the insert) believed “a film is not a book—it should not be broken up. It is a continuum and should be seen as such,” I thought it was pretentious. (I bought the movie and I can watch it however I want.) But I’ve come around to Lynch’s thinking, at least in this case: the film is one perfect dream and there’s certainly no other film in his catalogue in which every scene so perfectly follows its predecessor. By the time we get near the end, we are ready for a scene in which Alvin and an anonymous old man in a bar share their stories of World War II; Lynch has each actor deliver his story without flashbacks or other effects that would call attention to his presence as a director. There is no need to gild the lily and the entire film works this way. One should only see the very end and what happens when Alvin dismounts from his trailer if one has been with him on his journey.

None of this means that the film is a one-off in terms of Lynch’s output. It may be surprising that Lynch made a film so solidly rated G, but even his most R-rated work shares the same idea of a protagonist looking for meaning despite all of the obvious obstacles, dangers, and threats.

When Vladimir Nabokov was interviewed by Vogue in 1969, he was asked to describe his favorite meal. His response, “Bacon, eggs, and beer,” is a great surprise, since a reader would expect him to talk about quails’ eggs or confit de canard. His prose is certainly less simple than his purported favorite foods and the joke of his response is that the author of Lolita and Pale Fire would enjoy something so simple, so straight.

The Straight Story is Lynch’s bacon, eggs, and beer—or, as seen in the film, his braunschweiger.

Listen below or wherever you get your podcasts.

The Straight Story is a masterpiece. I love it so much. So vital. I was also enthralled with his Interview Project, where he traveled around talking life with folks from all walks of it. He had a range not many talk about, this was a great read.