Driving Life Into a Corner

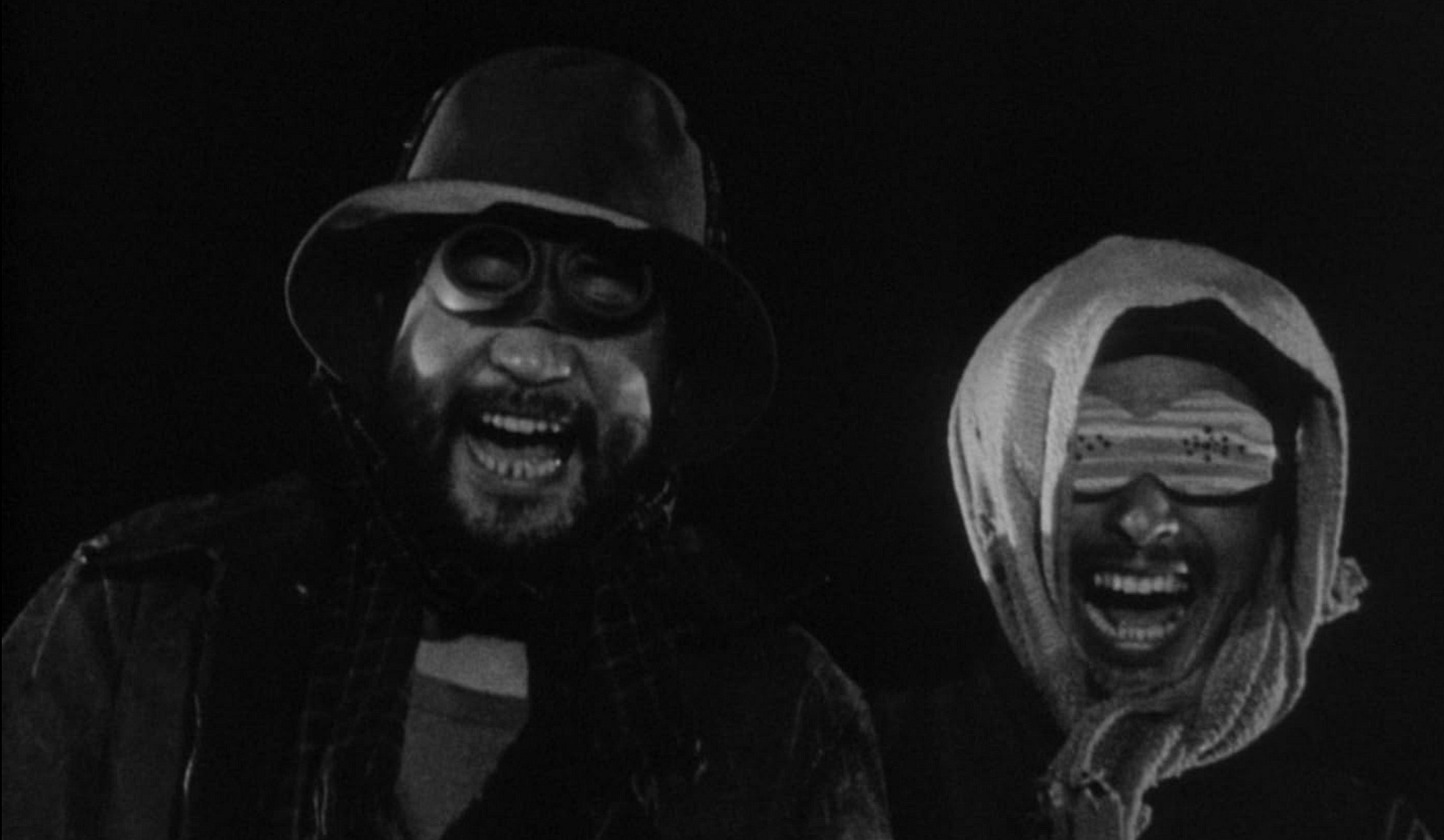

Woman in the Dunes

Here’s a post based on this week’s upcoming episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics and (at the end) a player that lets you listen to an ad-free version of the show before it officially drops. The post and the podcast don’t totally overlap: they complement each other. The post usually is a deeper look at an idea raised on the podcast. We take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done almost 300 and you can find them all here. You can subscribe to the show wherever you get your podcasts; please consider leaving a review on your platform of choice. Thanks.

One of the guiding principles of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics and of generally recommending movies or books to other people is that the less they know about what’s being recommended, the better. When we stumble upon podoworthy movies, Mike and I text each other with the phrase, “Don’t read anything about it.” Sometimes, this advice is moot: you don’t need to google Thirty Day Princess or Thief to get a sense of what they will be like. But sometimes—as with, recently, The Beast and Manchester by the Sea—the fun is going into it cold. (Neither of those movies are “fun,” but you get the idea.)

That’s exactly how I went into Woman in the Dunes. I knew of it but not anything about it, which made me the ideal first-time viewer. At first, it reminded me of Planet of the Apes (lost wanderer in a strange landscape), then Misery (man held captive in confined space with devoted woman), then Deliverance (hostile locals become increasingly dangerous), and finally, The Wicker Man (sophisticated man finds himself in what may as well be an alternate universe grounded in cruelty and superstition).

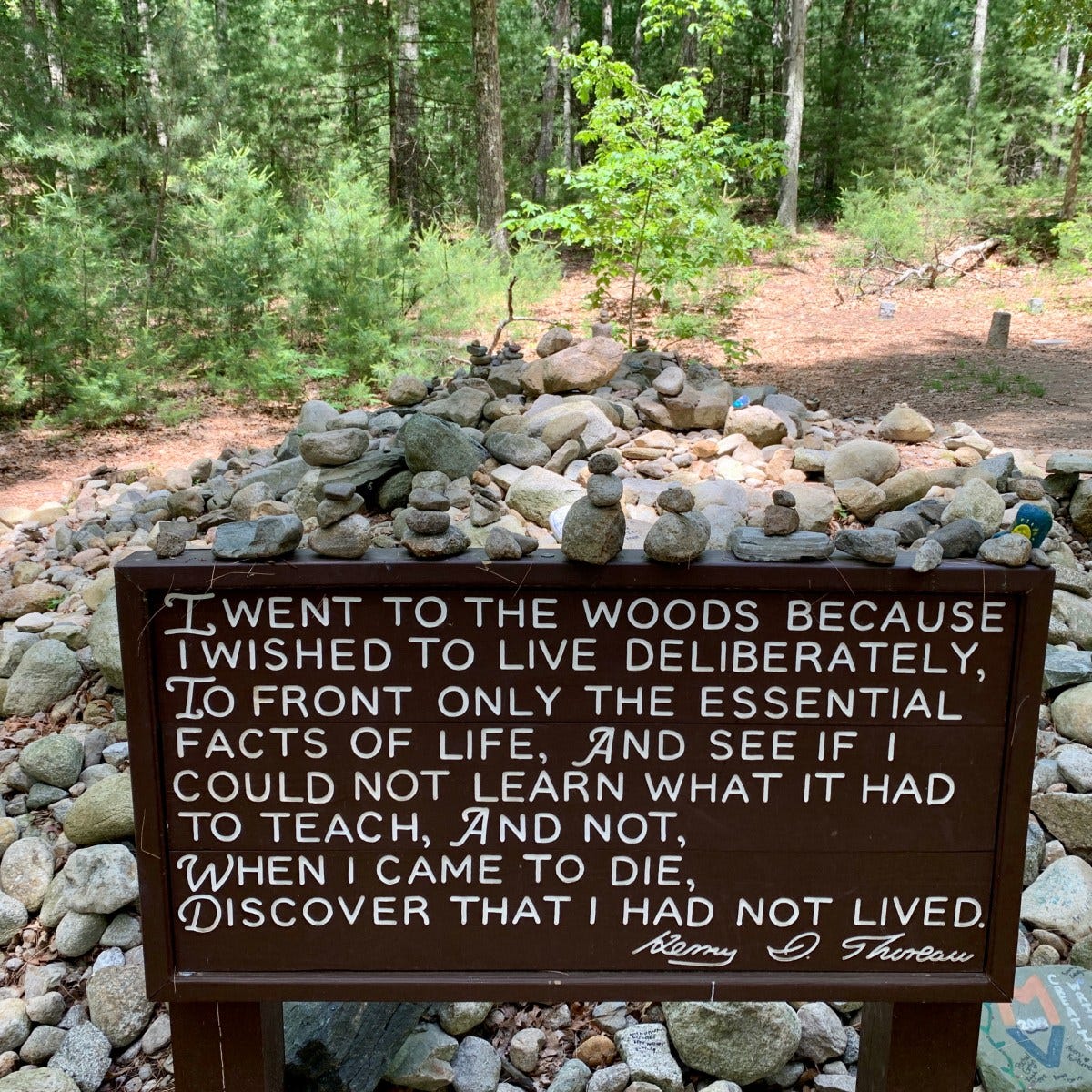

After thinking about the film at some remove, however, what it most calls to mind is Walden, Henry David Thoreau’s 1854 memoir about his life in the woods. I admire Walden and passages from it pop into my mind all the time, usually with the effect of me nodding along with their author, the way I sing along with Sinatra and tell myself that I don’t sound half bad. Someone writes about social media and I think, “We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate.” I find myself having to clean a stainless-steel kitchen garbage can, wondering why I bought another chore, and think, “I had three pieces of limestone on my desk, but I was terrified to find that they required to be dusted daily … and I threw them out the window in disgust.” I glance at the Fashion section of a newspaper and think, “The head monkey at Paris puts on a traveler’s cap, and all the monkeys in America do the same.” Thoreau makes his readers feel good about themselves, or at least inspired to “live deliberately” as he did for a time. His voice in Walden is part Marcus Aurelius, part Magic 8-Ball: you can open almost at random and find some insightful words that apply to whatever is bothering you that moment.

Woman in the Dunes is a great companion to Walden because it dramatizes many of its themes, but as a nightmarish photonegative. Thoreau said he wanted to “live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.” We often feel the appeal of that idea: to get away from civilization and really “live.” But would that always lead to a pleasurable series of epiphanies? Would the natural world always provide a backdrop against which we could explore our “real” selves? And do we really want to meet our real selves? In Heart of Darkness, Marlow learns that all the rivets that hold civilization together are much less binding than he thinks. He has to go to the Congo to learn this, but Woman in the Dunes shows us that a descent into a life without rivets is only a bus ride away.

The film and the memoir also make us consider fundamental issues about freedom–not political, but elemental and essential. Thoreau said that “a man is free in proportion to the number of things he can let alone.” All good and true: all of the nonsense with which we fill our days makes us prisoners, as Don Henley sang, of our own device. We see people enslaved by Instagram all the time and TikTok is such a malicious jailer because it tricks people into loving their cells. People become house poor because they “need” a finished basement, wine cellar, and five bedrooms—for two people. Others are caught up in office drama that keeps their imaginations caged and blurs their focus of what really matters. Freedom, to Thoreau, is freedom from the voices that yap at us all day long and prevent us from listening to our own. It’s freedom from objects we are told we need to be happy. But what if that freedom from social pressures and materialism reduces one to a new and worse kind of servant? What if the freedom from all that enslaves us transforms us into something more base and less complicated than we were? The ending of Woman in the Dunes is so shocking, so wrong, because we see a person come to love his enslavement. Some viewers may find the ending affirming and think that the man has been liberated and can now live a life of contentment. But as Samuel Johnson said in a similar context, “It is sad stuff; it is brutish. If a bull could speak, he might as well exclaim, ‘Here am I with this cow and this grass; what being can enjoy greater felicity?’”

Woman in the Dunes toys with these questions while simultaneously keeping its audience surprised and off-balance. It’s a movie in which everything is buried in sand and the sand is a metaphor for everything. It’s on the Criterion Channel now—watch it, but don’t read anything (else) about it.

Listen to the episode here and please subscribe on your favorite podcast provider:

Thought you’d like these.

I watched the movie recently and found your analysis stimulating. Jim Morrison sang “locked in a prison/Of your own devise.” I think he got it from William Blake.