Everyone has fretted about the death of the humanities, at least on college campuses. At Harvard, the number of humanities majors has halved in the last ten years, reflecting a nationwide emphasis on STEM (and the general love of an acronym that people can repeat like parrots). The decline in English and similar majors may reflect the growing assumptions that colleges—whose costs have outpaced inflation by roughly 180% over the past twenty years—should offer more quantifiable returns on investment. Much ink has been spilled about who (or what) is to blame, but the Academy should also take a look in what Elvis Costello calls the deep dark truthful mirror. I graduated with a BA in English in 1990 and just made it out the door while the flames of critical theory were doing more damage to the study of literature than those started by Caesar in Alexandria. When I earned my MA three years later, there were a few of us—students or professors—draped in fire blankets, but there were far more pyromaniacs who sought ashes instead of understanding. Critical theory became all the rage, often a literal one that, like a wave of Visigoths, sought to tear down the ways in which we used to read and respond to literature. This wasn’t political correctness or wokeness or decolonizing the curriculum—that all came later. It was simply a moment that took all of the joy out of reading. Everything was deconstructed, including one’s opinions about this very subject. The actual books we were supposedly studying receded into the background. Many (although thankfully, as we’ll see, not all) English departments paved paradise and put up a parking lot.

I taught literature for years as it was taught to me: text-centered close-reading that sought to understand how great art works and what it illuminates about the human condition. Students loved this approach, but over time, there were fewer of them. Nobody was majoring in English (or History, or Philosophy) any more and the course offerings withered on the vine—and with good reason. Wonderful surveys of the canon were seen as points of contention and were replaced by studies of minor works because professors earned their PhDs writing about them and now needed to “do something” with what they had written. I moved to teaching writing and research, which is exciting and fulfilling, and while I would sneak in as much literature as I could, I also missed the experience of reading and talking about literature with other people. That’s one of the reasons I became a teacher in the first place.

At some point last year I read about the Catherine Project, created in 2020 by Zena Hitz. Here’s a passage from the “About Us” section of the website, adapted from one of her essays:

The pinnacle of intellectual life, so far as I am concerned, is to sit around a table talking about deep questions, inspired by an excellent book. We are drawn to that table from a desire to understand and to learn, with and from one another. We read, speak, and listen, not to draw a boundary between ourselves and others, but to uncover bonds of human unity.

A professor at her alma mater, St. John’s College, Hitz wanted to replicate the idea of St. John’s Great Books program in virtual tables across the world. (Click on the link to see what freshmen there are assigned, a far cry from graphic novels and the kind of painfully bad “relevant” books that my own kids were assigned when they left the nest.) They now host over six hundred readers each semester.

The aim of the Catherine Project is to reawaken joy in the great books—and they are not afraid to say (or at least imply) that there is a canon and that some books are more worthy of intense study than others. Yet there’s no elitist vibe, reactionary slogans, or assumptions that anyone who doesn’t read Homer in the original Greek is a rube or that anything written after 1922 is not worth the paper. One of the core beliefs of the Catherine Project is that great books are for everyone who wants to pick them up and that everyone can benefit from reading them. “Universities are wonderful,” Hitz has written, “but they are not necessary in themselves for human flourishing.” Melville said a whale ship was his Yale College and Harvard; the Catherine Project takes a similarly unlikely setting—a Zoom meeting—and makes it the site of deep thinking and learning. It’s also free. For all of the talk about “equity” we hear, the folks at the Catherine Project are walking the walk.

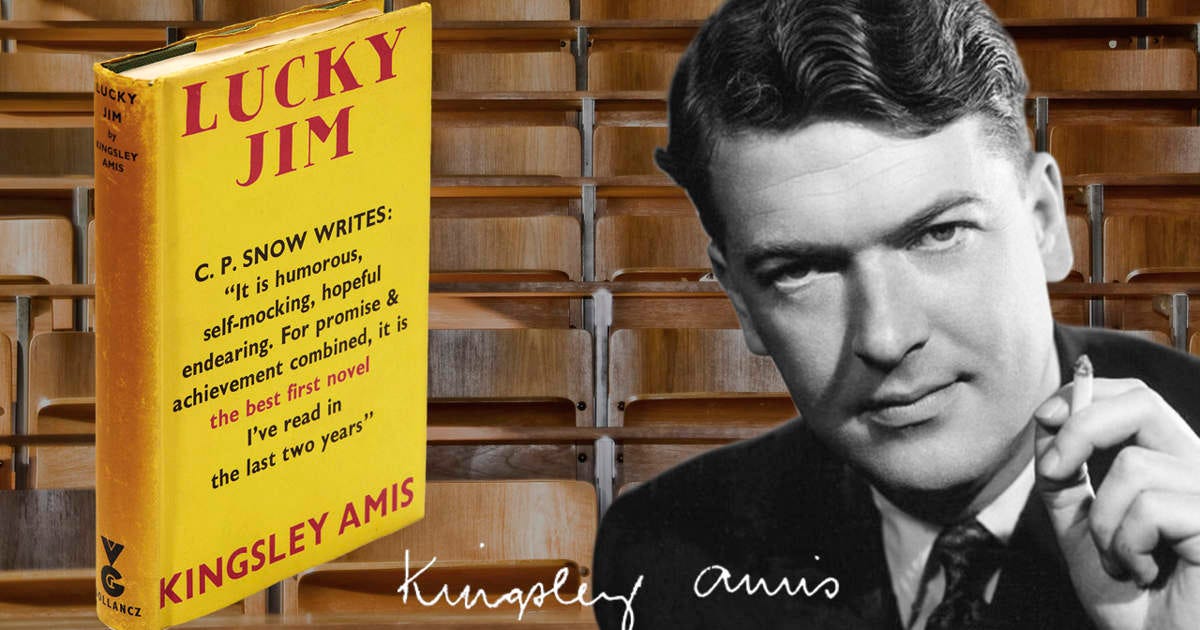

After reading about the Catherine Project’s mission, I knew I wanted to volunteer as a leader and emailed the directors. I was told that I should first take one of their courses to see what they are like—a great suggestion. I enrolled in one centered on two books about would-be scholars: Lucky Jim and A Confederacy of Dunces. (If you know these books, you’ll see how the “would-be” suits both of their protagonists.) I had read both of these before, but not in years.

The course was not like I expected in every good way.

The first thing I noticed was that the meetings lacked what an Anglo-Saxon might call Zoomdread, the deflation and irritation we experienced during lockdown as we dealt with initial social awkwardness and then sheer boredom in front of our webcams. Everyone’s cameras stay on during the meetings: this is crucial to Catherine Project practice and rightly so. As Stephen Dedalus tells his friend that he cannot discuss aesthetics with a mouthful of figs, the Catherine Project assumes that one cannot discuss literature with a collection of white fonts in black boxes. We need to see each other’s faces. The second cause for relief was that there was no sharing of slides, use of the chat feature, or the raised hand emoji. It really was like the physical room that Zoom seeks to mimic—and just as if we were all around that previously-mentioned table, there were times when four people tried to speak at once, when nobody spoke, or when someone responded to something said ten minutes earlier. In other words, it was a genuine conversation.

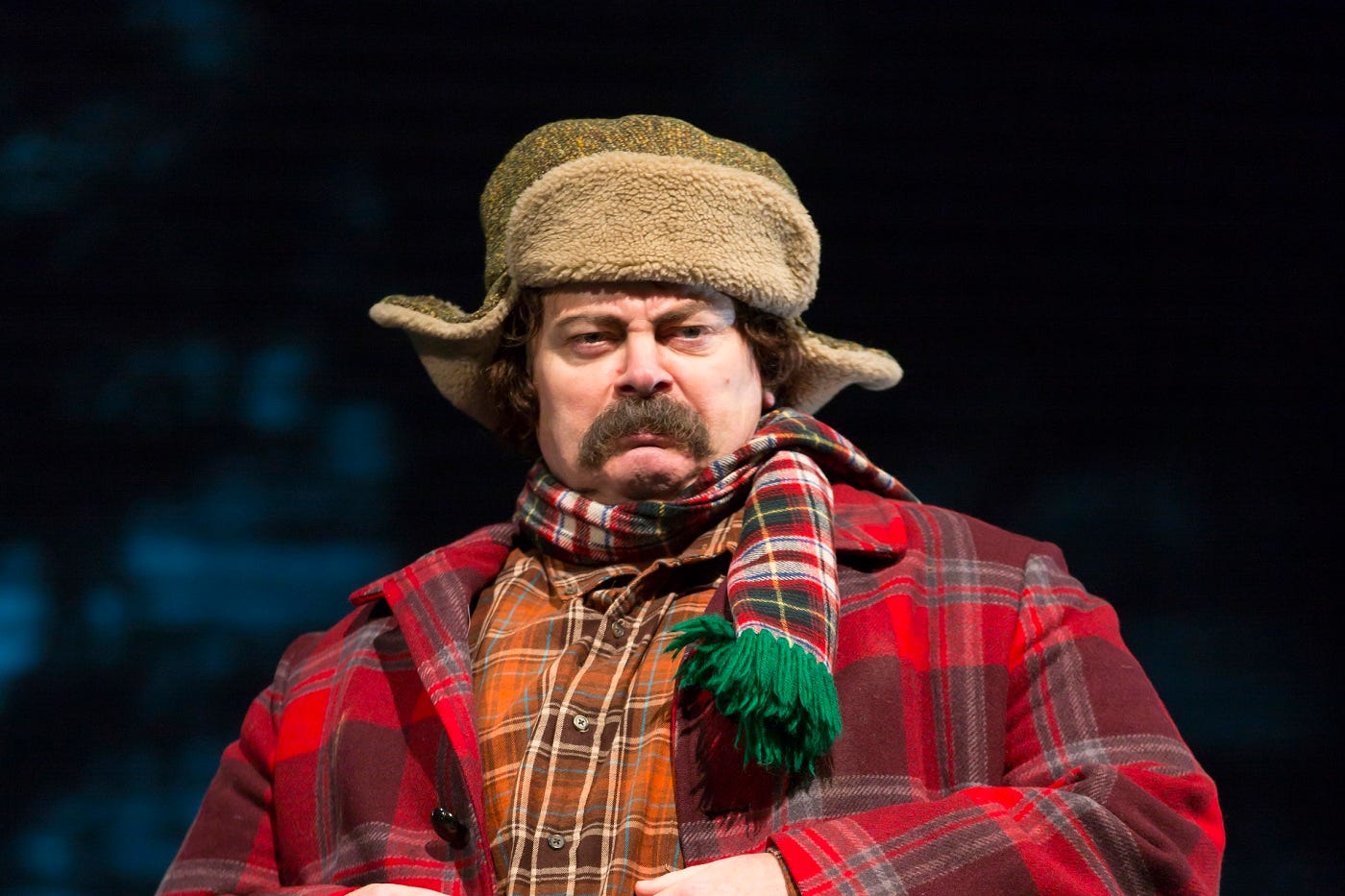

I learned that allowing for this authentic conversation is another core belief of the Catherine Project: while its reading groups are called “courses,” the leaders offer questions and moderate the conversations without steering them to particular endpoints. These aren’t courses in the sense of one person with all the knowledge offering it to the students as a gift or leading the discussion into a predetermined spot. While those experiences can be valuable, the Catherine Project reading groups are a bit different, since they allow the conversations to move where the participants want it to go. Regardless of one’s career, how many of us have been pulled into falsely-named “committees” in which we are asked to give our ideas, only to find that the decision has already been made and that anything we said was empty air? There’s a moment in The Simpsons in which Principal Skinner tells the students, “In the interest of creating an open dialogue, sit silently and watch this film.” Nothing like that happened: in fact, our leader would begin each meeting with a single question and almost never interrupt. One week, we were asked if we thought Jim Dixon had any real ambition or agency; another time we were asked what we thought about Ignatius Reilly’s relationship with his mother. We would begin with these questions and always refer to the text, but often found ourselves moving into new territory. And as is always the case after discussing a book, I came to regard both of the novels more highly than I did upon first reading them.

Another unexpected yet wonderful feature of this first course was that none of us talked about ourselves or came to know each other on a personal level. We introduced ourselves to each other on the first day, but other than that, all we knew of each other was (sometimes vaguely) where we were geographically during the meetings. I found myself identifying other readers by what they had said in the past about the books: one person from Florida brought up the undesirability of certain characters as husbands, one from the midwest spoke of how both Jim Dixon and Ignatius Reilly would fare in contemporary academia, and one from near Pittsburgh good-naturedly defended Prof. Welch, Jim Dixon’s addled boss, from our attacks. No time was wasted and each meeting was ninety minutes of pure book talk; we learned about each other’s ideas, not what we did over the weekend. Nobody was jockeying for a teaching assistant post or trying to schmooze a professor for a good grade. Someone would be silent for thirty minutes and then say something that made everyone quiet in the best way: good quiet, thoughtful quiet, as opposed to Zoom awkwardness. I was hooked.

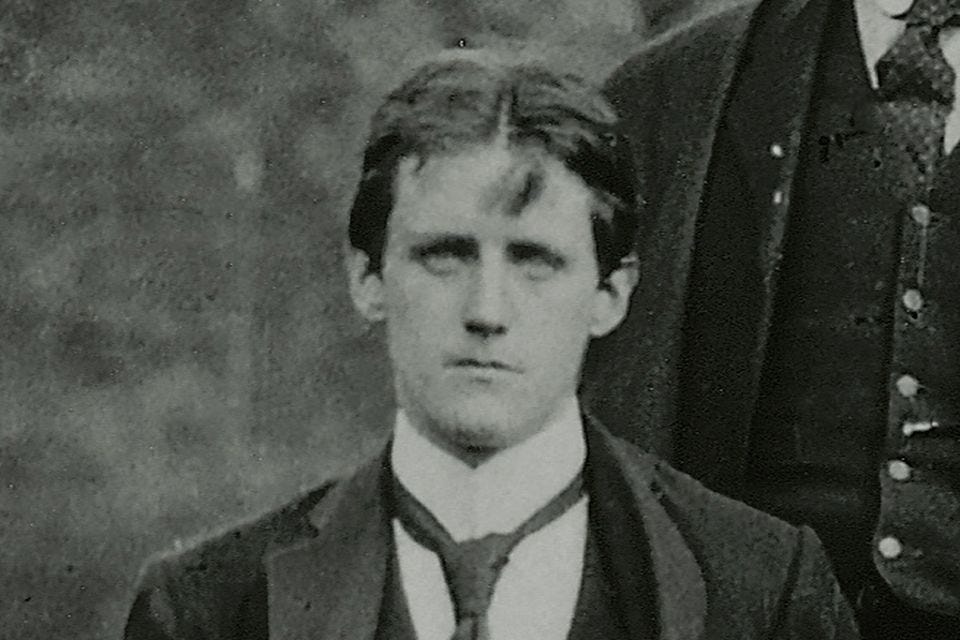

This past semester, I led a group on Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and participated as a student in one on Henry James’s The Wings of the Dove. I had taught Portrait in a classroom before, but didn’t want to constrain each meeting to fit my plan. I knew there were scenes we had to discuss—the pandybat, Christmas dinner, Stephen on the tram, the sermons—but I also knew that the conversation would naturally get to these moments. It would be impossible not to, like discussing Jane Eyre without ever alluding to Bertha or Moby-Dick without mentioning Ahab’s leg. Some of the readers had read Portrait (and Ulysses) before; others had never read past Portrait’s opening “moocow.” But we all clicked and began each week with a question, such as “How does Joyce convey the sense of childhood?”, “What do you notice about the structure of each chapter?”, “How would you describe the state of Stephen’s soul?”, and, “How is the novel like a portrait as opposed to other forms of artistic expression?” We talked and laughed and read passages aloud and nodded along with each other. It was great.

Think of one of your favorite books and somebody asking you if you’d like to talk about it to a group of people who are going into the discussion not to express why they find the book “problematic” or preen about how much they already know about it. This group would be composed of people who already like the book, are curious about why other people like it, or who have heard that it was great and wanted to give it a try. Would you want to join that conversation? Of course you would. That is the thrill of a Catherine Project reading group. I am still naive enough to be amazed that our Portrait group included readers from Maryland, Michigan, North Carolina, New Mexico, California, Toronto, Wales, and Nigeria. I was interested in what they underlined, what questions they had, and what they connected from previous conversations. And I’m not so proud to pretend that I wasn’t a little sad when it was over; at the end of the last meeting, I joked, “Let’s start Ulysses!” and received an email telling me we should do that very thing.

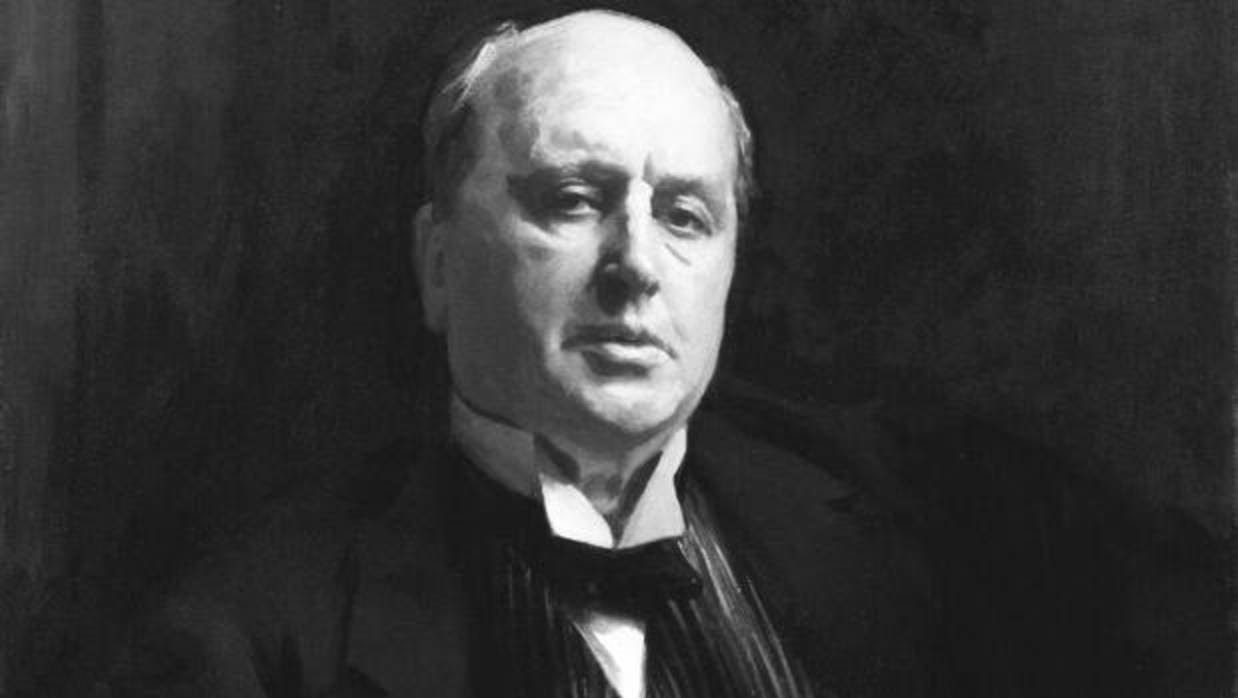

At our first meeting about The Wings of the Dove, I was delighted to see a member of the Lucky Jim group—it was Richard, the Defending Prof. Welch guy. I knew he had good taste! We each did a double-take and laughed; it was like bumping into a friend at the store. Anyone who has read Wings knows of its challenges: at times, it makes Ulysses seem like Hop on Pop. But John, our leader, always began with a question that sparked great conversations: “Is Kate insecure or clear-eyed?” “What grabbed you this week about Milly?” “What happened to make Densher ‘understand’—and what does he actually understand?” He would sometimes tell one of us, “Say more,” which would lead us down another avenue. As with the previous groups, I had no idea what anyone did for a living, where they went to school, or if they did—and, again, that didn’t matter. Some people talked more than others, but John always made sure that anyone who wanted to speak had the opportunity. We found ourselves thinking together, very hard, as James demands and rewards.

What’s valuable about Catherine Project courses is that I didn’t always agree with every point made, but I always greatly respected the people who made them. This is not what happens often in literary or certainly political discourse: Voltaire’s pledge to defend to the death his opponents’ right to speak has been replaced by the desire to cancel and dox, or at least roll one’s eyes. Granted, discussions about how much Milly Theale actually suspects about Kate Croy and Merton Densher are not going to (alas) provoke the same level of passion as contemporary politics, but the level of respect was obvious and refreshing. More than once, I thought something new about the novel. We never tried to “solve” it; instead, we dwelt inside its ambiguities and navigated them just as we did with James’s sentences, sometimes getting lost, but often striking gold. There were times when John would refer to a passage that I had bracketed and underlined and labeled with “!!!” in the margin; there were also many in which he or another reader referred to a passage about which I hadn’t thought as deeply. Ask twelve readers to find a key sentence in a chapter and you’ll get, if not twelve, at least nine different ones. And each answer led us into another investigation of James’s supremely complex prose and people.

We also developed running jokes. Some of us were on Team Kate: those who wished to defend the heroine from charges of the most cynical, machiavellian manipulation and instead understand (if not justify) her actions by invoking her backstory: her disgraced father! Her miserable sister! The whole setup! Others found themselves on Team Densher: those who claimed that the book was about Densher’s growing moral awareness and refusal to “go so far” (to use a Jamesian phrase) as his lover. The occasional debate continued until we hit the very last moment of the book at our tenth and final meeting. The Densherites noted that he doesn’t read Milly’s letter or accept the money: he has become a better man! But the Croyists responded by noting he remains absolutely passive, unwilling to take any action so he can pretend to be blameless—he is part of the same hypocrisy. This makes our meeting sound like a formalized debate, but it wasn’t; each time someone would raise a new idea about these people, he or she would get a lot of nods or facial expressions that read, “Actually, that’s true … I hadn’t thought of that.” The recognition that people on the page can be as complicated and contradictory as the rest of us is a great feeling to have when discussing a novel.

There’s even more to the Catherine Project than reading groups: they offer a core program in which participants take four twelve-week courses, intensive reading groups in which participants write, and tutorials in which students learn ancient languages.

If you really want to digest and “own” a book, teach it. If you

aren’t a teacher, talk about it with somebody. I read James’s The Ambassadors during lockdown, alone on my porch, discussing it with no one but myself. And while I recall the characters, general arc of the book, and “Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to,” I don’t own it as I now own (at least in some degree) The Wings of the Dove. But I heard a rumor that The Ambassadors will be in the fall course offerings, so I may need to join that group. It would be a mistake not to.

I read a lot of novels, probably >30 a year. I don't actually read them; I listen to them. I can do this because the nature of my work (for $$$) allows me to do so while I work. So I'm lucky. Were it not for audio books, I'd read just a few or even none.

Here, a newish medium (audio) helped literature-"reading" survive. But there's another newish medium that has, I think, really diminished literature-reading: video. The fact is people would rather watch than read, full stop. This is a strong and in-built (evolved) preference. Before the rise of video, "watching literature" was very hard to do because there wasn't much of it. Plays, and not many of those. Then movies, then TV, then (and especially) on-demand TV served up by the Internet. Now you can watch almost anything ever recorded any time you want. Why read a novel when you can watch a novel (so to speak)? And there is now a firehose of novels to watch. And all your friends are watching those novels. And they are talking about them, Should you spend your evenings reading a novel that nobody you know will read, or watching 5 seasons of "You" (just finished it) and gabbing about it with your friends?

Actually, "should" really has very little to do with it. These things (novels to be read) may be edifying, but they are still entertainment. And entertainment is all about what you *want* to do because it's, well, entertaining. Sure, you know you should read War and Peace. But you don't want to because there is a new season of "Downton Abbey" out. So you watch "Downton Abbey."

I don't know what all of this means, but it can't be good for the "humanities" insofar as the "humanities" is focused on reading.

An important article, that explains a few concepts I have been grappling with over the years. For a long time in college I was disappointed having not pursued the English major, but some courses just did not seem to click. There were professors who mentioned that classical literature criticism (looking solely at the work of art to derive meaning) was a theory that rose in the 1940s along with fascism.

Silver lining, Catherine Project has just received its largest student applicant pool with over 1000 entries. Personally I haven’t been placed yet, but Kristy has (Magic Mountain).