All best-of-anything lists should be viewed with one raised eyebrow. Anyone who really loves something (card games, birds, kids) should have a difficult time determining which are “better” or his or her favorites. In sports, one could rely on statistics, but people admire athletes for reasons besides how they perform. (Cristiano Ronaldo could go scoreless for the entire next season at Al Nassr FC and my son would find a reason why this adds to his lustre.) I love Henry James and James Ellroy, but the only thing they have in common are long novels about people at the ends of their ropes; to say which one I think “better” is to ask if a chair is better than a table.

I also confess an automatic eye roll when I read critics offering their obligatory ten best films or books of the calendar year. There hasn’t been a year since the recent turn of the century that had ten films one would earlestly recommend to friends with, “You absolutely have to see this.” And that’s what a best-of list should be: books and movies that one urges on anyone who will listen, the kind that you lend to people and then ask a few weeks later if they got around to them yet not because you want them back but because you want to see their reactions and have your enthusiasm confirmed.

That’s why my best-of-the-year list isn’t the best things I read or saw that came out this year, but the best things I encountered this year regardless of when they were made. In 1998, NBC ran a promo justifying a summer dump of reruns with the tagline, “If you haven’t seen it, it’s new to you.” Everyone mocked it, but NBC had a point. Anyone reading Moby-Dick for the first time this year would be silly to think, “I’d like to regard this as one of my favorite books this year but I could only do that if it were 1851.” That nobody in 1851 went around urging the greatest contender for Great American Novel on anyone suggests the narrowness of confining one’s best-of list to the calendars. Sometimes we, as individuals and a larger culture, need time to catch up.

The Wall Street Journal runs a feature every Saturday in which they ask a writer to name and justify his or her five favorite books about a different topic: last week, Charles Scribner III offered his five favorite books about family businesses, with publication dates ranging from 1597 (Richard II) to 2021 (Vanderbilt: The Rise and Fall of an American Dynasty). These are always interesting because they seem genuine: one reader urging favorites on another. We love the art first; everything else comes second.

Here are the best pages and frames I found in 2024, a year in which I read 57 books and watched 110 movies. I gave myself five in each category. I didn’t include long-time favorite books I reread this year (Norwood, The Friends of Eddie Coyle) or movies I watched again (Miller’s Crossing, Saboteur). These are all first-time encounters. The only caveat is that one of the books I would have included (Pictures at a Revolution) is described in greater detail in my Ten Best Books of the 21st Century post.

The Best Pages of 2024

Walter Tevis, The Hustler (1959). I had found this at a used bookstore and it sat on a shelf for years until I picked it up after rewatching Jackie Gleason play Paul Newman in Robert Rossen’s 1961 adaptation. What a great surprise to find the novel as rich as the film! Elsewhere on Substack, I’ve written about how Tevis dramatizes, through Fast Eddie Felson’s time at the table, the experience of “flow”: what psychologist Mhaly Czaimetinatli calls the state in which one loses self-consciousness and time slows because one is fully immersed in an activity. The Hustler is also a great look at the ways in which talent needn’t always be paired with maturity, an idea that Richard Price examined when he wrote the screenplay for The Color of Money. That’s also a great novel, but very much unlike Scorsese’s film. (There’s no Tom Cruise character in Tevis’s book.) I also wrote earlier this year about The Color of Money on the page and in the frames.

Daniel Boorstin, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-events in America (1962). I enjoyed Boorstin’s The Creators (1992) at a time when English departments still taught literature, knew Boorstin’s oft-quoted definition of a celebrity (“a person well-known for his well-knownness”) and his concept of “pseudo-events”: manufactured news first created to fill gaps on a page and now created, without pause, to fill gaps in our attention. What I didn’t know is the degree to which Boorstin nails the ways in which media unimaginable to him at the time now stand as Exhibit A of his thesis: so much of what passes for news is just a combination of fonts and ginned-up emotion. Boorstin asks us to consider that there are days when earthshaking important things do not happen—even in a world as hyper-connected as our own in 2024—but that we have all been trained to pride ourselves on knowing about current (pseudo) events.

Thoreau was already onto this in 1854: “Hardly a man takes a half-hour’s nap after dinner,” he wrote in Walden, “but when he wakes he holds up his head and asks, ‘What's the news?’ as if the rest of mankind had stood his sentinel. . . . After a night’s sleep the news has become as indispensable as breakfast.” I laughed to myself thinking of Boorstin and his wife reading the paper at the breakfast table and her saying, “I know, Dan, I know: it’s a pseudo-event.” That term is repeated throughout the book. But he certainly came up with a way to think about how we eagerly pay for killing time with the valuable currency of attention. Pseudo-events are, at best, a waste of time, but at worst, an insidious tool of mass manipulation. The Image reminded me of Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death and the book is written in a voice and style that is often missing from today's academic writing. He doesn’t spend half of each chapter saying what he will argue (“Rather, I argue that …”) or talking in circles: his prose is direct and clean. (He also avoids the hideous word “limning,” which every academic writer now seems required to use at least once to be taken seriously.) The Image is the kind of book you finish and then see examples of its argument everywhere—even in yourself. I know that I’ll read several descriptions of psuedo-events today. So will you.

Richard Stark, Dirty Money (2008). Richard Stark was the pseudonym of Donald E. Westlake, who chose it to match his experiment of writing about a character who expresses himself sparingly and only with reason; sometimes these expressions are words and sometimes they are gunshots. Over the course of twenty-four novels, of which Dirty Money is the last, readers get roughy the same pattern: they almost-always begins with the word “When” and some kind of wild action, as in, “When the woman screamed, Parker awoke and rolled off the bed” (The Outfit) or, “When “When the phone rang, Parker was in the garage, killing a man” (Firebreak). We then get the setup for the caper, something goes wrong, and Parker has to figure out how to extricate himself. The books are as elegant and brutal as their protagonist and there are times when my eyes wanted to move faster than my brain so I could see what happened next on the page. I came across The Hunter in 2016, the first of the Parker novels published in 1962, and was a little sad when I finished Dirty Money, knowing it was the last. Whether or not Dirty Money is the best Parker novel is irrelevant and like asking which is the best of the original Indiana Jones movies, which Roger Ebert compared to asking which is the best in a link of sausages.

Dirty Money is the final book but not a finale: Westlake died the same year this was published. That it reads like another Parker book rather than a big finish makes it all the more charming: better to leave the readers with a solid installment than to have Parker plunge into Reichenbach Falls. If you are familiar with Parker and Point Blank, John Boorman’s terrific adaptation of The Hunter, you can listen to my New Books Network interview with Eric G. Wilson’s book about it, and the episode of Fifteen Minute Film Fanatics where he sat in for a conversation.

Jessica Hooten Wilson, Flannery O’Connor’s Why Do the Heathen Rage? A Behind-the-Scenes Look at a Work in Progress (2024). The Divine Flannery was working on this, her third novel, when she died in 1964 at the age of 39. A portion was included in the Library of America edition of her complete works and that seemed to be that—until Jessica Hooten Wilson dove into the archives, read all of O’Connor’s drafts, and arranged them sequentially with editorial commentary as connective tissue.

There’s an argument to be made against reading this: it’s rough and unfinished and even us harmless drudges on Substack would hate to have our drafts posted here for all to read. When Nabokov’s notes for his died-while-composing novel The Original of Laura were published in 2009, a former professor of mine who adores every syllable of Nabokov’s oeuvre refused to read it, since Nabokov wanted it destroyed upon his death. And when the Prayer Journal O’Connor kept when she was at the University of Iowa was published in 2013, I felt uneasy about reading something so private and meant for other eyes even less than the draft of a novel. But it is great to hear her voice again, even if the novel enters familiar O’Connor territory of the know-it-all intellectual about to get his comeuppance. (You might want to hear my interview with Wilson on the New Books Network, see my video interview with her about the film Wildcat, and read her other work on her Substack, The Scandal of Reading.)

Daniel de Visé, The Blues Brothers: An Epic Friendship, the Rise of Improv, and the Making of an American Film Classic (2024). Like many men of a certain age, I can recite whole scenes of this movie the way my kids can do the “Band Geeks” episode of Spongebob. My initial reaction to learning about the book was a grouchy, “I wonder if it will start with the movie or we’ll get obligatory biographies of Belushi and Ackroyd and the SNL years.” I saw this as a setback, but I was wonderfully wrong. All of the lead-up to meting John Landis isn’t filler, but a look at the “epic” friendship of the title. Readers are reminded of just how wild the original SNL shows were (as opposed to the ghost ship that sails across people’s screens now) and how odd it was for Belushi and Ackroyd to create these characters who, initially, were not meant to be included in any skits or played for a laugh. They really wanted to share their love of music: that’s the “mission from God.” It’s also surprisingly touching when dealing with Belushi’s addiction and death. I’ve read a lot of how-this-film-was-made books and this is one of the best. You can hear my interview with Daniel de Visé here on the New Books Network and our Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics episode on The Blues Brothers here.

The Best Frames of 2024

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1947). A film I had read about but never seen, this is (like Tár, below) a movie that explores the workings of a creative mind and likens the writing of a book to speaking with a ghost. Of course, when the budding author is Gene Tierney and the ghost is Rex Harrison, we’re in for a lighter ride than Cate Blanchett having a nervous breakdown, but the central issue of where ideas come from and how the imagination works are treated with intelligence and wonder. It also has a great catch-in-the-throat, old-school ending that works despite the overall preposterousness of the setup—and it has George Sanders as the honey-tongued heel. I interviewed Nick Davis, Mankiewicz’s great-nephew and author of one of my Ten Best Books of the 21st Century about it: you can read my longer post and see the video of that interview here.

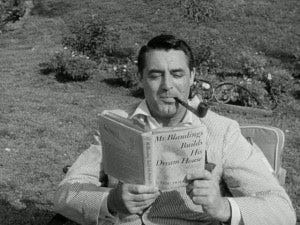

The Big Heat (Fritz Lang, 1953). The Criterion Channel’s Noirvember offerings each year is an array of movies that are fun to watch, even if they aren’t top-shelf. Not everything can be Out of the Past or Detour. But The Big Heat is a perfect movie that does everything a great noir does: it has a complicated plot, layers of corruption, fast dialogue, dangerous women, smoking—but also a recognizable human at its center. Bogart’s and Robert Mitchum’s cool factors put them in another universe: that’s their appeal. But Glenn Ford is more like a Jimmy Stewart everyman and as we watch him brought low because he tries to travel the high road, we find ourselves in a different kind of noir than expected. We also get Lee Marvin, Gloria Grahame, and the sister of one of the most famous actors. You can find my post about it and our recent Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics episode on it here.

Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World (Albert Brooks, 2005). After watching Rob Reiner’s Albert Brooks: Defending My Life, I was reminded of how much I love his movies and watched (or rewatched) all of them this year. Lost in America remains the best; I never saw Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World until I decided to complete the catalog. Maybe I had low expectations from a fear that the movie would be sentimental and like an ABC-Afterschool Special or make some kind of Important Statement, but all of those vanished ten minutes into the movie, which is one solid bit after another. The scene in which Brooks performs his famous ventriloquist sketch and chalkboard improv made me laugh harder than, I think, any comedy made after this one. I was so glad to be going through this Brooks renaissance that I watched all of his great Tonight Show appearances (The Speak and Spell! The Home Impressions Kit!), read a collection of interviews with him and interviewed the author for the New Books Network. I also read and enjoyed his novel, Twenty Thirty, and hope that he has one more movie in him to complement the rest of them. He’s 77, but seems like a young 77.

Manchester by the Sea (Kenneth Lonergan, 2016). In another post, I talk about my being late to the party on this one, although the word “party” doesn’t connect to the experience of watching this grim, stomach-churning movie that relies on pure human drama to upset the viewer, instead of gross-outs, violence, or (most impressively) actors yelling. The characters are well-drawn and complicated and the film has the texture of real experience. I wish it were marketed differently so that it didn’t look like a Hallmark movie; a lot of first dates must have gone sour after the would-be couple sat there as the credits rolled. But if any of those dates were between people who loved movies, they had plenty to talk about afterwards, including a scene between Michelle Williams and Casey Affleck that I’ve watched as many times as I could endure. As with The Gunfighter, discussed in this post, I was wrong coming into this and happy to be set straight, repentant sinner that I am.

Tár (2022). As with Manchester by the Sea, I was wonderfully wrong about this one, assuming it would be an op-ed about the patriarchy disguised as a movie. I reluctantly pressed play after a friend of mine urged it upon me as the greatest movie ever made about pretentiousness. After the scene in which Lydia Tár eviscerates a smug Juilliard student for his refusal to listen to Bach, I was amazed that it was even made; after the final scene (without the long end credits that Todd Field includes in the beginning, perhaps as a nod to all the assistants, like the film’s Francesca, in the world), I thought this was the closest thing to a Nabokovian portrait of an artist I’d encountered since rereading The Real Life of Sebastian Knight or Despair. People rave about Cate Blanchett and she’s terrific in this but she’s also in a movie so well-written that she doesn’t have to carry it alone. Often puzzling without being cute, Tár is a biopic of a fictional character that examines the ways in which all of us make fictional versions of ourselves for others—what T. S. Eliot describes as preparing “a face to meet the faces that you meet.”

If you’ve encountered any of these pages or frames this year or in another, I’d be interested to hear your thoughts. Best wishes for your 2025 reading and viewing lives.

Thanks for this - I've added plenty to my list from this post. Here's to 2025!

Oh the Ghost and Mrs Muir is such a touchstone for me. I knew the movie as a child but also fell in love with the 60s era TV show. Loved seeing this here.