(If you haven’t read the two preceding pieces on The Hustler, you may want to check them out first—but if not, that’s OK—this essay, like the film, doesn’t depend on knowing its predecessor. )

In the inverse of how we usually approach film adaptations of literary works, I met Fast Eddie Felson first on the screen and then on the page. I had seen Robert Bresson’s The Hustler many times, but it wasn’t until recently that I read and appreciated Walter Tevis’s 1959 novel. The same is true for The Color of Money, which I knew only on the screen as Scorsese’s terrific 1986 sequel, adapted by Richard Price. When I began reading Money, I assumed I would find the kinds of variants, additions, and subtractions one finds whenever comparing pages and frames and was ready to do what we all do after we engage in these kinds of comparative readings: begin sentences with, “You know, in the book …” as my friends and family moved to different rooms. I was in for a surprise: while Sidney Carroll’s screenplay for The Hustler is faithful to the novel (save for the fate of Sarah, the lush who sees Eddie as a path to respectability), Richard Price’s adaptation is radically different, plotwise, from Tevis’s 1984 novel–almost to the degree that Howard Hawks’s terrific To Have and Have Not differs from Hemingway’s mess of a novel.

The first thing anyone moving from Scorsese to Tevis will notice is that, on the page, Minnesota Fats is still a major character, even more than he is in The Hustler. The novel begins with Eddie visiting Fats in Florida, where he’s retired from pool and content living as straight-citizen George Hegerman. He’s put away his cue and tells Eddie that he “lives on investments”1 (a sign of the wisdom he will try to impart to Eddie) and has substituted shooting pool with a new hobby: photographing birds. His black leather case now holds a camera instead of a cue and Tevis describes Fats capturing the flight of three pink birds with the same cool movements he had in the pool room. Eddie gets “goosebumps” (4) at how Fats still moves well and the reader sees that Fats has found something new that allows him to enter the flow state (described in the previous essays on The Hustler) and give his life meaning. He isn’t interested in pool any longer for the same reason that Cary Grant stopped making movies in 1966, twenty years before his death. The thing that gave him flow and purpose was good to him and he respected it, but he didn’t want to tarnish it through abuse. Part of being mature is knowing when to quit, which was Eddie’s flaw the first time he played Fats in The Hustler.

Eddie has come to Fats with a business proposition: a cable TV franchise (loaded with early eighties sexy money) will pay Eddie and Fats to hold a series of exhibition matches at department stores, county fairs, and parking lots in the hopes that the broadcasts are picked up by Wide World of Sports. It sounds as shady to the reader as it does to Fats, who says he doesn’t need it. But Eddie keeps pressing him for financial and personal reasons. In his book on the nature and pursuit of flow, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi notes, “Having achieved flow in one area does not necessarily guarantee that it will be carried over to the rest of life”2 and Eddie’s life in 1983 epitomizes this idea. Eddie is now “Ed,” divorced, broke, and living in Lexington, Kentucky like a former racehorse wandering around a pasture. He’s been running a pool room instead of playing in one, which Fats dismisses as “a waste” (5). His refusal to work for Bert, the mobbed-up gambler, saved his self-respect but came with other costs: he tells Fats, “I scuffed in the little places for a few years” because “they’d have broken my arms if I’d played anything important” (11). The thrill is gone and pool has transformed from a source of flow to something with which he’s vaguely associated but which no longer brings him any pleasure—he’s the burned-out teacher, the watercolorist now selling picture frames, the ambulance drivers in Bringing Out the Dead. Later, Eddie’s new love interest, Arabella, tells him that Roy Skammer, a professor and mutual friend of theirs, hates teaching but “doesn’t have the strength to leave” and once tried to kill himself with pills because of what he saw as a lack of meaning in what used to be a former source of joy:

“He took a sabbatical to write a book and he didn’t write anything. Just hung around the house and tinkered with the plumbing. One morning he didn’t wake up and Pat took him to the hospital. They pumped him out.”

Eddie shook his head. “I wouldn’t have thought he was the type.”

“Well,” Arabella said, “there’s a lot of it going around” (147).

The lack of flow is a virus that Eddie has caught, despite his thinking that he was immune from it after beating Fats for a second time all those years ago: Fats telling him, “I can’t beat you” in 1958 was Eddie’s inoculation against a meaningless life. But now, Eddie is often “bored” (60) and when Fats asks him why he came to Florida to pitch his idea, Eddie says, "Well Fats, I didn’t have anything better to do” (8). This realization that he has been sleepwalking has prompted his trip to the Keys: while he does need the money, his deeper motivation is finding the flow that has eluded him all these years: “I want to do this, Fats,” he states. “I want to get back in it again” (12).

The catch is that he doesn’t, at first, want to do the work that’s required to relearn what he’s forgotten. That’s what makes Eddie such a believable person: we all talk a good game about our desire to reform our lives and take risks, but do we waffle when faced with the syllabus.

Fats, his opponent-turned-mentor, tells Eddie that if he wants to regain a sense of purpose, he needs to stop complaining about his fading talent and do something about it. After he beats Eddie repeatedly and tells him he’s no longer any good, Eddie hems and haws about how he’s only playing pool because he doesn’t know anything else: “It bores me, Fats. I mean it seriously bores me” (55). So much for wanting to get back in it again! Boredom is the kiss of death for the seeker of flow and Eddie’s moping begins to irritate his former rival, who tells him that he needs to rediscover his chops and stop kidding himself about what makes him happy:

“I can have self-respect doing something besides shooting pool.”

“No you can’t,” Fats said. “Not you.”

“Why not? I didn’t sign a contract that says I shoot pool for life.”

“It’s been signed for you” (56).

The rest of the novel is Tevis dramatizing a person’s return to that which once gave him meaning. By the end, Eddie catches up to what Fats and already knows and what Csikszentmihalyi states in Flow:

If a person sets out to achieve a difficult enough goal, from which all other goals logically follow, and if he or she invests all energy and developing skills to reach that goal, then actions and feelings will be in harmony, and the separate parts of life will fit together–and each activity will “make sense” in the present, as well as in view of the past and of the future. In such a way, it is possible to give meaning to one’s entire life (214-15).

And lest the reader think that Csikszentmihalyi sounds idealistic here, Fats explains to his pupil that this is a real phenomenon in the real world:

“Practice eight hours a day. Play people for money.”

“I don’t know …” Eddie said.

“I know,” Fats said. “If you don’t practice, your balls will shrivel and you won’t sleep at night. You’re Fast Eddie Felson, for Christ’s sake. You ought to be winning when you play me. Don’t be a goddamned fool.”

“You make it sound like life and death.”

“Because that’s what it is” (56).

Eddie’s exhibition matches against Fats are doomed from the start because he’s going through the motions, assuming that what he used to be is still good enough to carry what he is now. He can’t compete well enough with Fats to make the games interesting and suspects that Fats is missing shots on purpose to give the spectators something for their money. Fats still has it: close to seventy, he “seemed far younger than that” (18) and “circled the table as he had in Chicago twenty years ago when Eddie himself was young and hungry” (18). Eddie knows talent when he sees it: “Fats went on shooting and Eddie kept racking the balls and sitting again. It was beautiful to watch—he didn't care who won” (19). Early in Money, Eddie is the once-great actor who tells himself he’s happy doing dinner theater: he can avoid the fear of failure that accompanies taking bigger risks—but those risks are what make the activity, and one’s life, meaningful. The Hustler is a portrait of white-hot talent without maturity; The Color of Money is one of maturity when the talent has cooled.

As viewers of Scorsese’s film know, Fats does not appear for a single frame; he isn’t even mentioned. The film has other major differences from the novel, such as the previously-mentioned Arabella, the divorced wife of a professor with whom Eddie opens a folk-art store that sells handmade quilts (you read that correctly): after the exhibition matches prove to be a bust, Eddie wants to go legit, just like Michael Corleone claims to want, on a grander scale, in The Godfather Part II. There’s a nice touch about Eddie working at the student union, renting pool tables to college kids who are oblivious to his reputation and don’t care that he has refurbished the tables so that the balls roll more smoothly. But the most notable difference is the complete absence of Vincent (Tom Cruise) and Carmen (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio). A first-time reader of the novel who knows the film will keep waiting for Vincent to walk into the student union or appear at a bar, but like Godot, he never shows, even as a minor character. These differences, however, do not detract from the strength of either version: The Color of Money in both forms explores the desire for a once-great talent to “get back in it again” and the work that entails. Both Eddies have laid down their cues and both find their past source of flow slowly reawakened and then impossible to shake. By the time Price finished the screenplay, Scorsese called action, and Newman said his first line, the plot had radically changed but the issues had not.

Price’s version mildly refutes the notion that Scorsese’s film is a sequel, which has come, probably rightly in our current moment of endless reboots, prequels, “reimaginings,” and metaverses, to be a somewhat pejorative term, or at least one that makes film lovers roll their eyes in exhaustion at Hollywood’s inability to create anything new. (“They’re making a movie called Brody about the life of the New York cop before he gets transferred to Amity Island!” etc., etc., etc.) The Color of Money isn’t about a rematch (Rocky II), the next adventure of a hero (Goldfinger), or the continuation of an established story (Aliens). “There will always be people,” according to Scorsese, “who will look at this picture and say, ‘Well that's it—that's a sequel.’”3 Scorsese is correct in describing the film as something different from the next step in Eddie’s life. At the end of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen Dedalus is 20; in Ulysses, he’s 22 and that’s the last we see of him. But what would he be like at 50? What would he think of himself? What would he have done with the talent that once made him think he was immune from the cares of the workaday world? That’s the experiment that Tevis and Price attempted with Eddie Felson. Both of them tell the same story with almost entirely different plots and both exceed the (often low) expectations brought about by the word “sequel.” One isn't better than the other; they complement each other as few sets of pages and frames do. Both include the Balabushka (Eddie’s lightsaber of a cue), the “two brothers and a stranger” con, and the nine-ball tournament at the end—but those are almost incidental to the common arc of Eddie once again breaking down, rebuilding, and moving toward victory. In the novel, he wins thirty-thousand dollars; in the film, he regains his self respect with the bang of a break and the words, “Hey … I’m back.”4 Scorsese again: “Essentially, we were determined not to make this Rocky with a pool cue or Top Stick.” The team had every opportunity to make an embarrassing, straightforward sequel, but instead made something wonderful that stands on its own without competing with the source material. One isn’t better than the other; combined, they show us what happens when (as Price called Eddie), an “adjunct professor in the art of cynicism”5 begins believing in again in the very talent that he had put away as a childish thing.

Price’s version came about largely because of the urging of its star, who loved the book and asked Scorsese in 1984 if he would be interested in directing. Like Fast Eddie, Paul Newman wanted to get back in it again. Tevis himself had written an adaptation that was more traditional in terms of mimicking the novel, but Scorsese wanted to create something that didn’t depend on knowing the backstory. Price was brought in and the three of them brainstormed for a year (imagine those conversations!) about Eddie and his situation. Newman frequently asked for rewrites and Price obliged, with Scorsese reminding him that anything he wrote had “to come through Paul Newman's lips.” Fats was, at one point, included in the film, but Jackie Gleason said the addition “seemed like an afterthought.”6 We’d all naturally love to see him playing Paul Newman again, but who can doubt The Great One? Like Fats in The Hustler, Gleason had the wisdom to know when it was time to quit.

One of Price’s challenges is that the best moments in the novel don’t concern pool. Consider one of many terrific passages in which Tevis enters Eddie’s mind to dramatize his assumptions about the connection between talent, flow, and a meaningful life:

People thought pool hustling was corrupt and sleazy, worse than boxing. But to win at pool, to be a professional at it, you had to deliver. In a business you could pretend that skill and determination had brought you along when it had only been luck and muddle; there were well paid incompetents everywhere living rich lives. They arrogated to themselves the plush hotel suites and Lear jets that America provided for the grateful and lucky far more than it did for the wise. You could fake and bluff and luck your way into all of it: hotel suites overlooking Caribbean private beaches; blow-jobs from women of stunning beauty; restaurant meals that it took four tuxedoed waiters to serve, with the sauces just right, the lamb or duck or terrine sliced with precise and elegant thinness, sitting just so on the plate, the plate facing you just so on the heavy white linen, the silver fork heavy, gleaming in your manicured hand below the broadcloth cuff and mother-of-pearl buttons. You could get that from luck and deceit, even while causing the business or the army or the government that supported you to do poorly at what it did. The world and all its enterprises could slide downhill through stupidity and bad faith, but the long gray limousines would still hum through the streets of New York, of Paris, of Moscow, of Tokyo, though the men who sat against the soft leather in back with their glasses of twelve-year-old Scotch might be incapable of anything more than looking important, or wearing the clothes and the haircuts and the gestures that the world, whether it liked to or not, paid for and always had paid for.

Eddie would lie in bed sometimes at night and think these things in anger, knowing that beneath the anger envy lay like a swamp. A pool hustler had to do what he claimed to be able to do. The risks he took were not underwritten. [...] Under whatever lies might fill the life, the excellence had to be there. It could not be faked. But Eddie did not make his living that way anymore (186-87).

This is terrific and a professor could lead a discussion of this passage and how Tevis articulates Eddie’s anger and self-pity. But translating these ideas into cinematic action is another issue, as Price (also an accomplished novelist) knows from experience:

What you bring from novels over to screenplays is nothing but trouble. Because the elements that make a novel memorable are death in a screenplay: the life of the interior mind, the psychological history, the author’s ability to speculate and create commentary, the weave and texture of the narrative, the words—none of this is relevant in a screenplay (viii).

Tevis’s novel is filled with the life of Eddie’s mind and commentary on his situation, even more than we find in The Hustler. (Money is also twice as long.) There are other great passages to close-read, such as when we learn of how Eddie abandoned his talent for the sake of a safer, more stable life as a poolroom owner in Lexington; his relearning his way around a table as he plays the Japanese shark Billy Usho; or his epiphany that “by starting to play again, to put his nerve and skill on the line, he had awakened something in his soul that was not easy to stifle” (186). But these needs and awakenings must be translated into visible action for an audience sitting in the dark. This is why Price’s sessions with the director and actor were so important: “We worked from the premise of what happens to a man when you take away his art,” Price explained, “whether it’s pool playing, writing, directing or acting.”7 This could have made their version something like Death of a Salesman with Paul Newman insisting on a dignity that he’s long lost and yelling, “I AM NOT A DIME A DOZEN! I AM EDDIE FELSON!” Instead, to again invoke the Rocky movies, they made it more like the best parts of Creed: a look at how a former champion finds meaning in guiding a younger person. That’s the core of the story and why everyone who saw Creed was more interested in an aging Rocky being diagnosed with cancer much more than the obligatory fight at the end against an opponent whose name none of us can recall.

In the film, this younger person is Vincent: a flow-seeking machine who is in almost the same situation as Eddie was in The Hustler. Filled with piss and vinegar, he’s loud, flashy, and not even aware that he can parlay his talent into real money or meaning. He reminds Eddie of himself all those years ago. According to Scorsese, “The kid plays the game purely for the poetry of it” and his calling Vincent “the kid” shows how Price and Tom Cruise approached the character: he sells toys during the day and wears his work T-shirt that reads “VINCE” when he’s playing pool, which Eddie later says is a nice touch to provoke others into underestimating him. As a scholar of “human moves,” Eddie sees what Vincent cannot and tells him so when he takes him and his girlfriend, Carmen, to dinner:

EDDIE: You’re some piece of work.

VINCENT: I’m some piece of work.

EDDIE: You’re a natural character.

VINCENT (to Carmen): I have natural character.

EDDIE: No … no … That’s not what I said … you are a natural character … you’re an incredible flake … I'm serious … It’s a gift … guys work all their lives to develop a character like that … You go into a pool hall guys nowhere in your league would fight each other to play you … you’re a masterpiece. (Vincent is silent; he doesn’t know if he should be insulted or not. Carmen is all ears.) You got all that but the fact of the matter is, kid, the way you go about things .. you couldn't find big time with a road map. (Eddie pauses to let that sink in. Pool excellence is not about excellent pool. It’s about becoming something (16-17).

We often lament that we wish we knew then what we knew now, and Eddie mentoring Vincent is making the wish come partly true. Vincent has a lot to learn about “becoming something” that can turn his talent into money and a name; there is no better onscreen depiction of flow than Tom Cruise singing “Werewolves of London” as he (naturally) performs his own shots as he takes down one opponent after another, but Eddie knows that one can only show off to this degree for so long. He tells his student that money won is twice as sweet as money earned, because money won is the result of managing and controlling one’s talent instead of having it control you, as it does when Vince uses his Balabushka like a sword and sings along with Warren Zevon.

To Price’s credit, Eddie has not become too good a professor of human moves and the third act concerns Eddie’s discovery that he isn’t as smart as he thought—a surprise for the viewer who has been watching a sixty-year-old Paul Newman who looks as cool as anyone could at any age. After a hustler named Amos (Forest Whitaker), humiliates him on the table and mocks him as he takes his winnings, Eddie loses his confidence as a player and teacher. Telling Vincent and Carmen, “You really have to put in the time and the effort to show your ass like that” (88), Eddie tells Vincent “I got nothing else to give you” (91) and doesn’t bother to try to make Vincent understand. They meet again at a nine-ball tournament in Atlantic City; when they play each other, Eddie wins—only to find that Vincent “dumped” and let Eddie win in order to collect a big payoff and take his revenge for abandoning him. (Never was a student so upset about a teacher canceling class.) Eddie fell for the same con, “Two Brothers and a Stranger,” that he taught Vince earlier, and Eddie forfeits his next game after a few shots.

Some of Eddie’s being-brought-low is in the novel: the night before he has to play for the tournament championship, Eddie has a triumphant win of $2500 at an offsite poolhall, only to find that he was the mark in the Two Brothers and a Stranger con: while he did see the color of money, “Eddie was the stranger and his win meant nothing” (270), since his opponent had thrown the game. His confidence is shaken, but since there’s no Vincent to refute, the action is all internal—which makes for great reading but also reminds us of what Price meant about bringing novels to the screen as “nothing but trouble.”

The pages and frames do come together thematically at the end of each version. In the novel, Eddie rediscovers his love of pool and reenters the flow state as he beats Babes Cooley for his shot at the championship:

He had entered that time zone he had nearly forgotten, where his stroke was not only dead-on but where his mind could somehow arch itself above his game and see the great simplicity and clarity of what he was doing on this green table with its spinning balls. Time passed without moving, until the PA system voice said, “Ten games to four. Fast Eddie,” and the applause washed over him, bringing him back. (277)

He then beats Earl Brochard, the same person who duped him as one of the two brothers, for the title and “had never felt better in his life” (293). On screen, Eddie cannot reenter the tournament, having forfeited, but this doesn’t matter because he wants to play for something other than money. He meets Vincent in a practice room and says “Give me your game,” but Vincent, still a youth, remains hurt by what he regards as Eddie’s betrayal. He relents after Eddie implores him: “I’m asking you … I got no leg to stand on with you … but I’m asking you … right now … give me your game … I got no time for jumps or hustles anymore” (116). Vincent agrees and thinks he is playing Eddie both for pity and the envelope of money he refused after the Two Brothers con, but Eddie reveals he is playing for bigger stakes: when Vincent asks, “Eddie, what are you going to do if I beat your ass?” Eddie prepares to break:

EDDIE: You ain’t kicking my ass anywhere.

VINCENT: What makes you so sure?

EDDIE (concentrating on the cue): Hey … I’m back (118).

Both versions see Eddie returning to the activity that gave his life meaning and that he thought he had lost as an older man. Will he prove to be as good now as he was when he was Vincent’s age? That’s not important. “He’s playing pool again. Whether he's going to make a career out of it again or get his chops back, we don't know, but at least he's doing something to heal his soul.”8 In the final freeze-frame after Eddie breaks, we hear Eric Clapton sing, “It’s in the way that you use it,” which is what both versions of Fast Eddie Felson have learned, over the course of two novels and films, about their talent.

Tevis, Walter. The Color of Money, Warner Books, 1984, p. 8. All subsequent parenthetical references are from this edition, which is the paperback released a year after the hardcover.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. HaperCollins, 1990. p. 214. All subsequent quotations are from this edition.

Forsberg, Myra. “The Color of Money: Three Men and a Sequel.” New York Times, October 19, 1986, p. 21. All subsequent quotations by Martin Scorsese are from this source.

Price, Richard. The Color of Money in Three Screenplays. Houghton Mifflin, 1993, p. 118. All subsequent quotations from the film are from this edition.

Gabler, Neil. “A Special Angle of Vision: An Interview with Richard Price” in Three Screenplays, p. x. All subsequent quotations from the film are from this edition.

Forsberg, 21.

Forsberg, 21.

Gabler, xi.

I will search out these books and fully agree with Price's view on what is naturally lost when novel is put to film..it's been decades but the most affecting parts of the Tooth Fairy's background is lost when Thomas Harris' tight Red Dragon was filmed as "Manhunter".

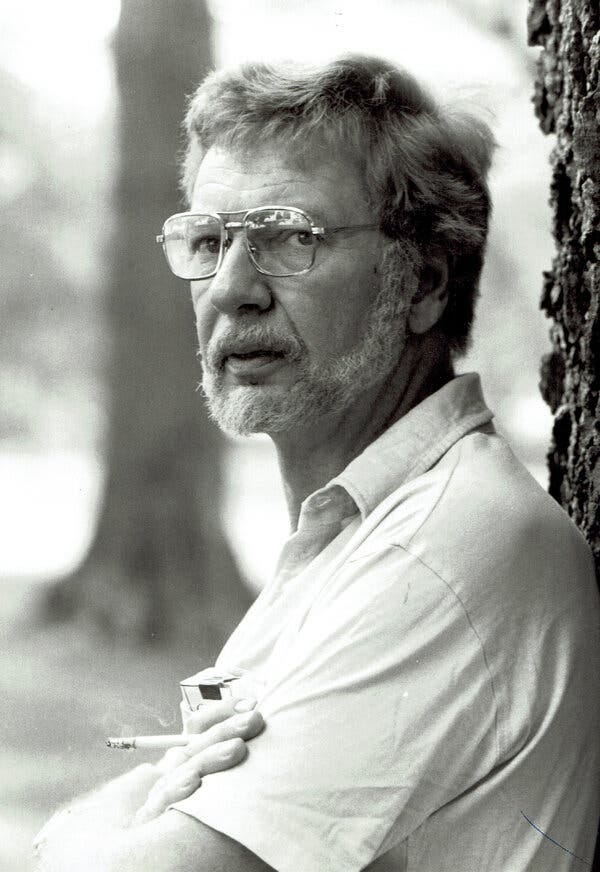

Walter Tevis is one of my very favorites. I'm glad he got more attention following "The Queen's Gambit." His sci-fi novel "Mockingbird" is absolutely fantastic.