Here’s a post about this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics. We choose the films almost at random: one of us will watch (or rewatch) something and text the other guy. We then record without any previous conversation, recreating the enthusiastic conversations people have in their cars on the way home from the theater. We also take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over 250 and you can find them all here. Spoilers always abound.

Pedantic readers and film fanatics never tire of pointing out that Frankenstein is not the name of the creature, but his creator. This explains why they are often home alone, reading and watching old movies.

But what fewer of these people point out is the alternate title of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel: The Modern Prometheus.

Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to humans, so that they might better improve their lot and strive higher. But the gods didn’t want any mortals striving towards the height of Olympus and therefore bound Prometheus to a rock and had his regenerating liver eaten out of his guts each day by a vulture (or eagle, depending on the source). There are secrets that only the gods can know.

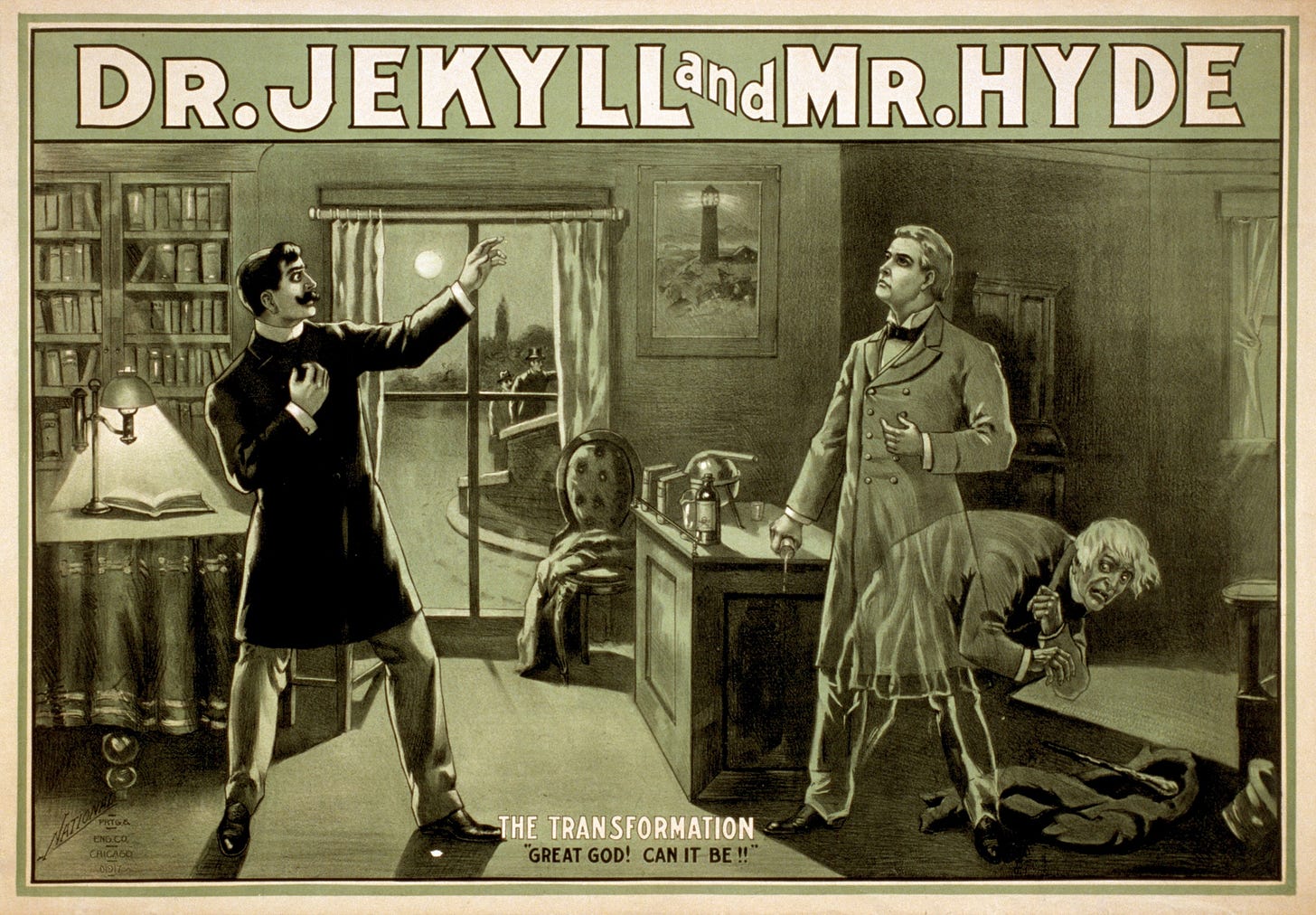

Literature is filled with scientists and scholars whose grand visions consume them but who can’t see what may follow the realization of their ideas. Victor Frankenstein aims to conquer death for the benefit of all: “I will pioneer a new way,” he states, and “explore unknown powers, and unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation.” When he fulfills his plan and creates a man, his creation demands things (a bride, status as a fellow human, answers to eternal questions) that Victor cannot or will not give him. Faustus wants to gain knowledge beyond what he learned in Wittenberg and assumes he will be able to gain enough of it to nullify his deal with the devil. Once he gains “power, honor, and omnipotence,” he will become his own god. Henry Jekyll thinks that if he could split himself in two, “Life would be relieved of all that was unbearable; the unjust might go his way, delivered from the aspirations and remorse of his more upright twin; and the just could walk steadfastly and securely on his upward path, doing the good things in which he found his pleasure.”

But we all know that none of these will work. Frankenstein dies in the Arctic while pursuing his creature, Faustus is dragged to hell, and Jekyll commits suicide to prevent another, stronger outbreak of Mr. Hyde. Visionary that he was, Jekyll couldn’t see what, years later, G. K. Chesterton could see perfectly: “The real stab of the story is not in the discovery that the one man is two men; but in the discovery that the two men are one man. The point of the story is not that a man can cut himself off from his conscience, but that he cannot.”

Shelly calls her hero the modern Prometheus, but he would be more accurately called a modern one. As in literature, our history is filled with figures whose incredible visions, once realized, came with unforeseen ramifications. Steve Jobs imagined a world in which humans interacted with technology; the first iMacs had handles, not so they could be carried around, but to suggest that it was OK to touch them. From there, it was a direct line to the always-touched smartphone, which has become the boon and curse of the twenty-first century. The incredible strength of Frankenstein’s creature is nothing compared to that of the iPhone—and the iPhone is far more destructive.

Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum), is another of these visionaries. He has a noble goal (eliminate the need for transportation) and the means to realize it (grants that fund the building of two pods in his laboratory). When Veronica, a reporter played by Geena Davis, asks him the routine question, “What are you working on,” he replies, with dead seriousness and without self-parody, “I’m working on something that will change the world and human life as we know it.” And like his literary ancestors, he’s initially excited and even messianic when he has his first taste of victory. Veronica’s unwillingness to use the teleporter is met with scorn:

You’re afraid to dive into the plasma pool, aren’t you? You're afraid to be destroyed and recreated, aren’t you? I'll bet you think that you woke me up about the flesh, don’t you? But you only know society’s straight line about the flesh. You can’t penetrate beyond society’s sick, gray, fear of the flesh. Drink deep, or taste not, the plasma spring! Y’see what I’m saying? And I’m not just talking about sex and penetration. I’m talking about penetration beyond the veil of the flesh! A deep penetrating dive into the plasma pool!

Those same English majors mentioned at the top of this essay will point out that Brundle is playing off of poet Alexander Pope’s “Pierian spring” of knowledge–and might also note that he leaves off the more famous line that precedes it: “A little learning is a dangerous thing.”

The Fly dramatizes, with great skill and economy, the danger of too little learning—of vision without wisdom. It has the perfect three-act structure, ending exactly when it should. Jeff Goldblum gives four incredible performances: the awkward dreamer, the impassioned visionary, the arrogant success, and the broken victim. The practical effects and makeup (designed by Chris Walas and Stephan Dupuis) are more convincing and striking than they would have been were this made today with bales of money and cold CGI. The music, like that in so many other 80s films. doesn’t date it. And despite the utter preposterousness of its premise, the final moments, in the midst of their full-assault grotesqueness and hysteria-inducing shock, achieve more pathos than hundreds of films touted as “emotional.” Brundlefly moving the gun is more moving than schoolboys standing on their desks.

Our modern Prometheus thought he was becoming “the best version of himself,” but he was tricked by the gods, whom Gloucester discovers, use us for their sport. His punishment—to become literally fused with his own invention by which he hoped to steal fire—is as horrifying as being chained and repeatedly pecked.

Postscript: The Brundlefrock

I assume that readers who have made it this far are familiar with the original version of The Fly (1958), directed by Kurt Neumann. But I learned more about the source of that movie from my co-host, Mike: It turns out that that Neumann’s film was based on the work of an author I’ve admired for decades without knowing his contribution to cinema: it was one of the great figures of twentieth-century verse who first imagined the story of a visionary with a fly in his philosophical ointment.

In 1910-11, while living in Paris and Munich, T. S. Eliot became fascinated with the idea of self-transformation and began drafting a poem about an indecisive man wishing he could be someone else, but also realizing that he could never be other than who he is. The lines

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two

were composed with this theme in mind. Deciding to make the idea of transformation literal, Eliot imagined J. Alfred Prufrock not at a party where the women come and go, talking of Michelangelo, but in a laboratory where he has created two telepods. The lines we all know in which Prufrock dismisses his companion’s concern—

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

—originally read,

Oh, do not dwell on the esplanade;

Just get into the telepod.

Eliot’s notebooks are filled with such revisions. Readers who know the published version from 1915 will be amazed by his original, Brundlefrock versions of lines that have become second-nature:

Shall I pull out my hair in clumps?

Do I dare puke upon a peach?

Or shall I burst upon you from the ceiling, out of reach?I have heard the women shrieking each to each;

I do not think they will give genes to me.

Eliot died in 1965 and left no record of his opinion of Neumann’s film. We do know that his favorite film was Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood, but imagine that, had he lived another twenty-one years, he would have been impressed by Cronenberg’s realization of the original Brundlefrock: a true connection of pages and frames!

Listen on the player above, on the New Books Network, or wherever you get podcasts.

That's not true about TS Eliot, is it?

This piece is a banger.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com