The Friends of Eddie Coyle

Another Day at Work

Here’s a post based on this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics and (at the end) a player that lets you listen to an ad-free version of the show. The post and the podcast don’t totally overlap: they complement each other. We choose the films almost at random: one of us will watch (or rewatch) something and text the other guy. We then record without any previous conversation, recreating the enthusiastic conversations people have in their cars on the way home from the theater. We also take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over 275 and you can find them all here. You can subscribe to the show wherever you get your podcasts; please consider leaving a review on your platform of choice. Thanks.

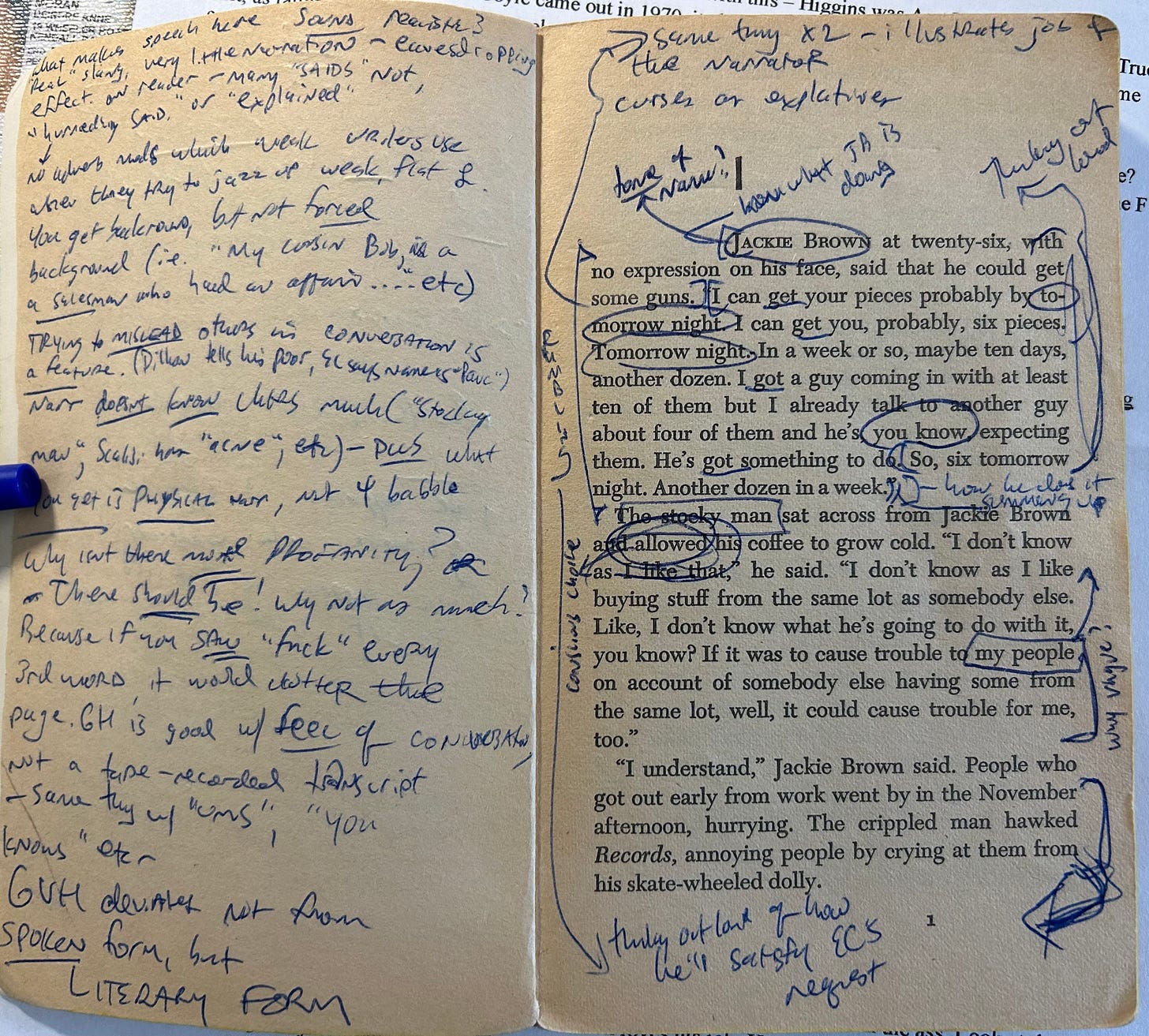

The Friends of Eddie Coyle begins like this:

Jackie Brown at twenty-six, with no expression on his face, said that he could get some guns. “I can get your pieces probably by tomorrow night. I can get you, probably, six pieces. Tomorrow night. In a week or so, maybe ten days, another dozen. I got a guy coming in with at least ten of them but I already talk to another guy about four of them and he’s, you know, expecting them. He’s got something to do. So, six tomorrow night. Another dozen in a week.”

The stocky man sat across from Jackie Brown and allowed his coffee to grow cold. “I don’t know as I like that,” he said. “I don’t know as I like buying stuff from the same lot as somebody else. Like, I don’t know what he’s going to do with it, you know? If it was to cause trouble to my people on account of somebody else having some from the same lot, well, it could cause trouble for me, too.”

This kind of dialogue may seem easy to write, but anyone who has ever tried knows it’s almost impossible. Here, we get everything we need to know about these two guys and the rules of their worlds in a handful of near-grunts. Jackie Brown says “pieces,” not “guns” as he performs for his buyer, putting on a show of thinking aloud to impress upon him how much he’s in demand, before verbally punctuating his words (“So”) and making his final offer. The stocky man, who we learn is the title character, doesn’t say, “No” or “Wait” or ask a question. He, too, is stating his position while also trying to insinuate his importance. “I don’t know as I like that” conveys doubt about Jackie Brown’s proposal as well as the stocky man’s age and prerogative: the offer is one that he has to like. Jackie Brown needs to do more and the stocky man has the right of refusal. He, too, avoids the word “guns,” using “stuff” and “it” while he conveys his understanding of how the world works and why he has to think about himself as the representative for his “people.”

When I was younger than Jackie Brown, one of my professors gave me a copy of the novel when I mentioned to him how much I enjoyed reading about criminals. He had extra copies of his favorite books that he would give to deserving students and I remember being surprised by this one: I was an English major—sure, things like Eddie Coyle were fun to read, but shouldn’t I be reading more Keats, James, and Shakespeare? I didn’t know that the music found in the works of these writers could also be heard (if faintly) in a book like this one. I’ve since read it several times and I’m always amazed by how the book carries its reader along in a series of conversations that move so quickly yet reward close-reading. The book reads itself to you like a criminal nanny.

Wordsworth wanted to bring poetry “near to the language of men.” Higgins wanted to bring the language of men near to poetry—and Eddie Coyle is his Lyrical Ballads.

The novel concerns bank robbers, mobsters, cops, gunrunners, and a hitman—but the most exciting action occurs in bars, bowling alleys, parked cars, and lunch counters as the characters talk to each other in a series of sales pitches, veiled threats, and complaints. Nobody watches Hamlet and asks where Claudius bought the ear-poison, which is one reason why Eddie Coyle is so interesting: it flips the usual focus from the big crime to the guy who supplied the tools. And if Higgins’s Elsinore is Boston Common, Eddie Coyle is its Rosencrantz (or Guildenstern): someone on the fringe of greater events who thinks he’s being careful but who finds he really doesn’t know what’s happening.

Higgins served as Assistant United States Attorney for the District of Massachusetts until the success of Eddie Coyle, his first novel, nudged him toward private practice and then writing full time. When the novel was published in 1970, it was praised by the New York Times as “the most penetrating glimpse yet into what seems the real world of crime” and other critics voiced similar praise for its realism. The Boston Globe said it “rings as true as a police siren,” Publishers Weekly called it “authentic down to the last gritty detail,” and the Washington Post said that “the life Mr. Higgins describes is as he describes it.” Norman Mailer had the best of these, exclaiming, “What I can’t get over is that so good a first novel was written by the fuzz!”

Everyone loved the realism, but a more accurate word is “realism.” I have no idea if actual gunrunners are as interesting as the people in these pages or if their dialogue is worth overhearing. I’d bet that it’s not. What’s absolutely realistic, however, about Eddie Coyle is how everybody in it—just like the reader—is constantly negotiating to just get to the next step of what he needs by the end of the day. Eddie negotiates with Foley, the detective, about what he could do for “uncle” (Sam) in the hopes that Foley will put in a good word about an upcoming sentencing. Jackie Brown negotiates with the savvy Eddie but also moronic hippies who want to buy machine guns. Even the bank robbers negotiate with the tellers and hostages. In Training Day, the viewer gets a glimpse of an inner sanctum of criminals (judges, elected officials, police brass) who meet in a dimly-lit restaurant booth to talk about their plans. Eddie Coyle isn’t getting within fifty feet of that booth or even of the restaurant. His story—the real realism—is about going to work and being someone in middle management who has to answer to all kinds of people and wants to just get his part of the process complete so he can move on to the next thing. It’s about the guy in Purchasing who won’t sign the form you need so that you can tell the client that yes, everything is in motion, because that guy in Purchasing thinks that you’ve cozied up to the Senior Vice President of Acquisitions for a job that he’s had his eye on for months. It’s about having to speak in a conciliatory tone when trying to wrangle a favor from the guy in the next cubicle. It’s about having to set someone younger than you straight when he acts like he’s under pressure and won’t give you a straight answer, as when Jackie Brown tries to explain to Eddie that he can’t get him the pieces he promised:

“Now look,” Jackie Brown said.

“Now look, nothing,” the stocky man said, “I’m getting old. I spent my whole life sitting around in one crummy joint after another with a bunch of punks like you, drinking coffee, eating hash, and watching other people take off for Florida while I got to sweat how the hell I’m going to pay the plumber next week. I’ve done time and I stood up, but I can’t take no more chances. You can give me a whole ration of shit and this and that, and blah, blah, blah. But you, you’re still a kid and you’re going out and coming around and saying: ‘Well, I’m a man, you can take what I say and it’ll happen. I go through.’ Well, you’re learning something too, kid, and I advise you, you better learn it now, because when you say that, when you get me out there all alone on what you say, well, you better be there in back of me. Because once you say it’s going to happen, it’s going to fucking happen, and if it doesn’t you got your cock caught in the zipper but good. Now I don’t want no talk and shit from you. I want ten guns from you and I got the money to pay for them, and I want them tomorrow afternoon at the place where we were before, and I’m going to be there and you’re going to be there with those goddamned guns. Because if you’re not, I’m going to come looking for you, and I’ll find you, too, because I’m not going to be the only one that’s looking and we know how to find people.”

In a book praised for “dialogue so authentic it spits” (Life), this is one of the few times in the book in which a character uses four-letter words; in real life, these guys would curse much more frequently, but Higgins knows that too much of it will make it less effective when it appears—call it the Anti-Scarface Technique.

As if dealing with people at work weren’t already a series of eye rolls and shaking heads, The Friends of Eddie Coyle was almost thirty years ahead of The Sopranos in its study of a criminal who has to also deal with domestic life. When Eddie meets Jackie Brown in a supermarket parking lot to pick up the pieces and Jackie notices bags of actual groceries in Eddie’s cart, he asks him, “Your wife make you do the shopping too?” Eddie responds with one of the most accurate statements about marriage ever recorded in the pages of a novel:

“My friend,” the stocky man said, “you don’t have much time and I’m kind of in a hurry myself. I don’t have time to explain married life to you, and besides, you wouldn’t believe me anyway. I didn’t believe it when they told me, and you wouldn't believe it if I told you.”

When Eddie asks Foley to take a ride and visit the U. S. Attorney who will be requesting Eddie’s upcoming sentencing for driving a truck filled with two hundred cases of stolen Canadian Club, Eddie tells Foley that he needs a break: “I got three kids and a wife at home, and I can’t afford to do no more time, you know? The kids’re growing up and they go to school and the other kids make fun of them and all.” We never think about fictional criminals’ kids, but Higgins does. And just like at work, Foley doesn’t care about the other guy’s kids. He wants names—if Eddie gives him some, then maybe Foley will make a call.

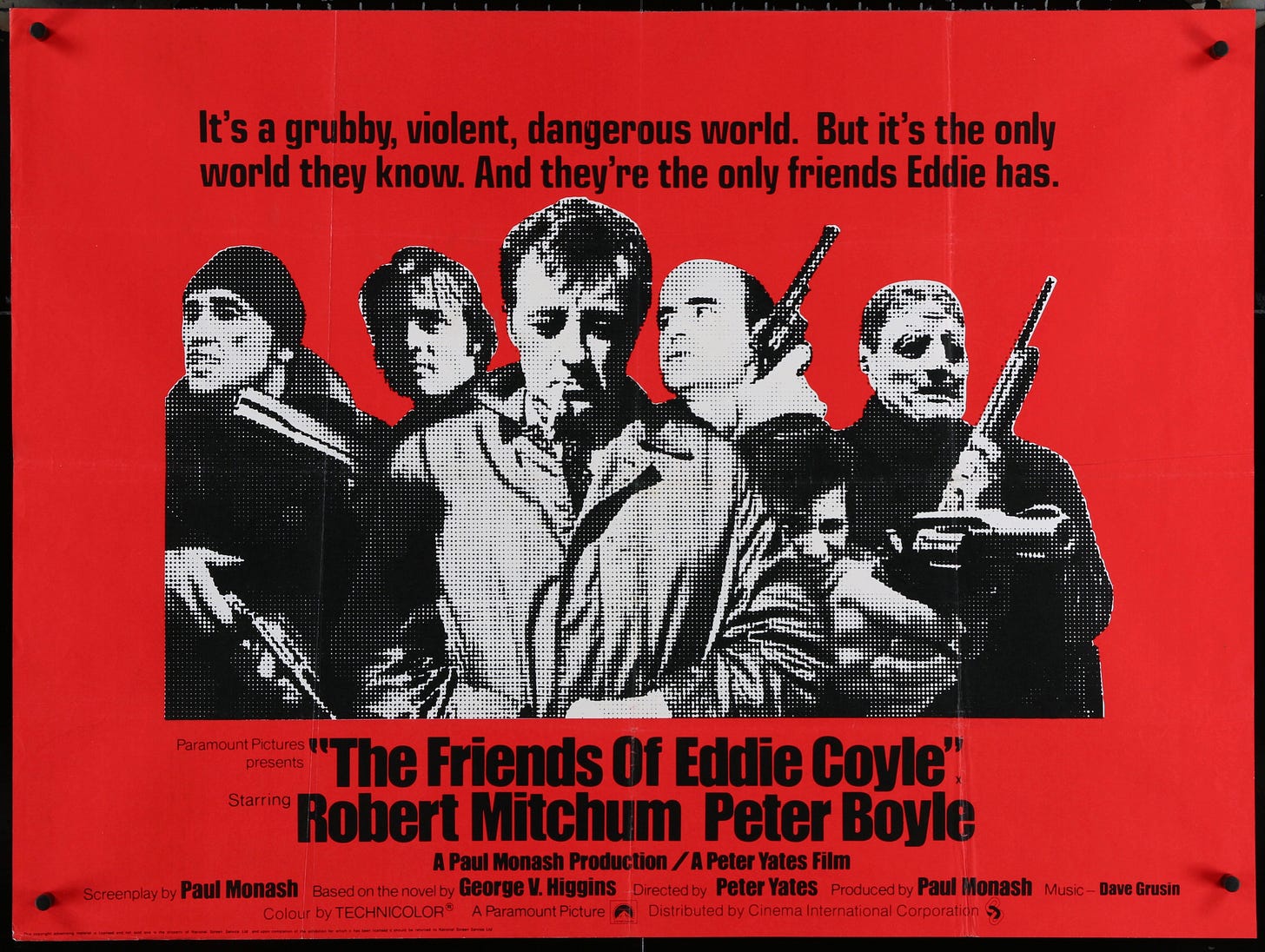

Peter Yates’s 1973 film is an object lesson in how to faithfully adapt a novel to the screen. It stands with John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon and the Coens’ True Grit as an example of a screenwriter (in this case, Paul Monash) sitting with the novel propped open on his desk so he can type the dialogue word-for-word in screenplay format. Huston’s version of Falcon was the third attempt to adapt it for the screen and the Coens’ True Grit was the second; both of their versions are superior to their predecessors because they knew what was great about the novels and transferred that greatness to the screen. Everything in Yates’s adaptation seems pulled from the reader’s imagination and rings true: Dillon’s bar, the garbage cans outside of Eddie’s house, the train station, the cars, the grey sky, the lack of joy. One of the bank robbers in Heat (Tom Sizemore) says that “the action is the juice,” but here the juice is warm and flat. Even the bank robbers might as well be punching a clock. The same is true for the cops. Dave Foley (perfectly played by Richard Jordan) works as many informants as he can and dangles the possibility of making a phone call on Eddie’s behalf, but only if he gets something to advance his career. He looks, talks, and negotiates like everyone else in the movie. Monash never tries to improve the novel by changing anything in it; there is one change in the plot involving Dillon, Foley, and the mobster Scalise, but it’s a move that makes the action move more smoothly. Here’s Monash’s version of Eddie’s previously-quoted speech to Jackie Brown:

I read once that John Huston said 98 percent of the success of a movie depends on the screenplay, 1 percent is casting, and 1 percent is everything else. That formula works for the adaptations I mentioned as well as Eddie Coyle. Only a 53-year-old Robert Mitchum could play Eddie with such resignation and subtlety; he’s still totally cool, but you wouldn’t want to be him for ten minutes. He looks every bit the exhausted middleman who wants to get to Florida. Peter Boyle is perfect as Dillon and any movie goes up a notch when it has Alex Rocco—two years before he proclaimed, “I’m Moe Greene”—as one of the gang.

Watching Eddie Coyle is watching a man die in slow motion in a world that will forget him before he’s cold. After all of his Hamlet-like indecision, Eddie decides to stand up and not give any of his friends’ names to Foley. He’ll serve his time and hope there’s something waiting for him when he gets out. It doesn’t matter: what matters is that the unseen boss thinks Eddie did, and that leads to the same result.

Here’s how the novel ends: Jackie Brown has been arrested and arraigned. Foster Clark, Jackie Brown’s lawyer, talks to the prosecutor—more guys punching the clock. As two lawyers engage in their own negotiations about what Jackie Brown can do to get an easier ride, Clark has a moment in which he forgets he works in a world that operates like a George V. Higgins novel:

“And in another year or so,” Clark said, “he’ll be in again, here or someplace else, and I’ll be talking to some other bastard, or maybe even out again, and we’ll try another one and he’ll go away again. Is there any end to this shit? Does anything ever change in this racket?”

“Hey Foss,” the prosecutor said, taking Clark by the arm, “of course it changes. Don’t take it so hard. Some of us die, the rest of us get older, new guys come along, old guys disappear. It changes every day.”

“It’s hard to notice, though,” Clark said.

“It is,” the prosecutor said, “it certainly is.”

Anyone who’s ever thought that if he died at his desk his job would be posted on LinkedIn before the funeral will find kindred spirits among the friends of Eddie Coyle.

Here’s the Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics episode on The Friends of Eddie Coyle:

"This kind of dialogue may seem easy to write, but anyone who has ever tried knows it’s almost impossible. Here, we get everything we need to know about these two guys and the rules of their worlds in a handful of near-grunts." I'm reading it now (on your recommendation), and you are exactly right. I'm thinking David Mamet (one of my favorites) may have read "Eddie Coyle." or some other Higgins. Or maybe they were separated at birth?

Loved this book since I was a kid. What a writer!