At some point in the early 1990s, the study of literature changed from an appreciation of books to an assault on their authors’ supposed moral failings. When I first read Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness thirty years ago, I felt scared at how out of my depth I had wandered. Conrad was smart and his intelligence intimidated me. But things have changed. Today, arch, overly-ironic hipsters stomp into undergraduate literature classes to tsk tsk Conrad as a poor benighted soul—if Conrad is even assigned. Many students have been trained to label writers from the past as unfortunate reflections of their times, mouthpieces for the privileged, or Western canon poster boys. Wielding terms like agency or otherness, these students do everything to books but what their authors wanted them to do: read them and have honest reactions.

I was taught to analyze and develop an appreciation for a writer’s craft choices. My classmates and I asked ourselves questions about word choice, structure, rhythm, and wholeness–some of the same ideas that interest Stephen Dedalus in Joyce’s Portrait. This led to a lifetime of pleasurable reading and a greater appreciation of how fiction works. Many contemporary students, however, are taught to be suspicious of writers’ motives. They ask themselves questions about social constructs, intersectionality, and (to use a particularly hideous phrase) “liminal spaces.” So much effort is spent on demonstrating one’s superiority to a text and its author and the jargon reinforces this feeling of superiority. (That’s the role of jargon: to mark oneself, like Aristotle in Dante, as the maestro di color che sanno, master of those who know.) Even worse than obscure prose that nobody enjoys reading, jargon on the page and in the mind prevents readers from having raw, emotionally troubling encounters with authors who might otherwise kick them square in the behind—and, after all, isn’t that one of the most satisfying experiences great literature delivers? Kafka said the books we read should wake us like blows to the head, but many readers want to soften that blow with the padding of theory and poses that help them lessen the impact.

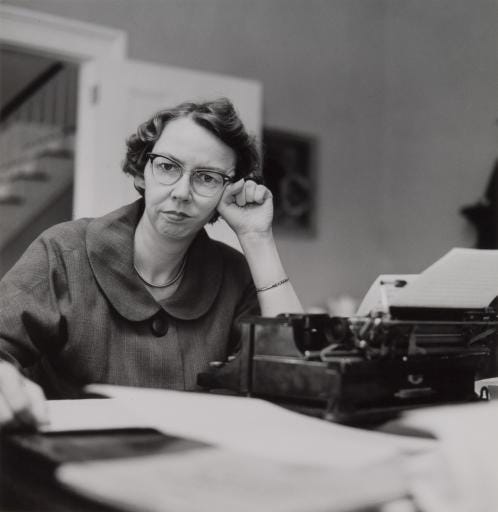

And that’s why I urge people to read the work of Flannery O’Connor.

O’Connor, who would have turned 100 today, presents an especially daunting case for post-post moderns and similarly-minded readers because Roman Catholicism informs every one of her sentences. If Conrad makes these readers uneasy, O’Connor makes them apoplectic. Wait, they say. Is she for real? Does she really believe all this stuff about baptism and sin and redemption and . . . Jesus? They never question her artistic performance. Instead, they question her assumptions about God, faith, and the fallen human—stuff that draws ire. And why not? Many students have been trained to regard Christianity and those who attempt to write about it with suspicion, even hostility. Make no mistake: O’Connor understood this well. So much so that, time and again, she was able to turn her critics into some of her most vivid characters. And yes, she did believe what she wrote in her books. Every single word. Her unapologetic belief is refreshing to Christian readers in a world where atheists seem to get all the press and the best publicists. You don’t need to be a Christian to appreciate O’Connor; you simply have to acknowledge that there are ideas from Christianity that can be taken seriously.

Some of my former students had a hard time with O’Connor’s convictions, as well as her lack of caginess in expressing them. One time I assigned the collection A Good Man Is Hard to Find and asked my students to write a response. A student emailed to say he’d found the stories “detestable” and “hateful.” He asked if he could write about that instead. Note the irony here: rather than relinquish his superiority over a writer, he tried to change the assignment in order to maintain his status quo. O’Connor faced the same challenges from her first readers in 1952, when Wise Blood was published and critics couldn’t tell if she was endorsing, mocking, or sympathizing with its protagonist.

Of course, that student is not alone. These days, Christian values are only mentioned when late-night comedians and mainstream intellectuals use them as target practice. But this is another reason (besides her sheer talent as a stylist) why I find her work so valuable. O’Connor depicts the need for Christianity in a world that lost its way two thousand years ago, when the crucifixion (not comic books, rap, or the internet) marked our moral decline. Consider a letter she wrote in 1957 regarding the title of her second novel, The Violent Bear It Away:

I'm still not sure about that title, but it’s something for me to lean on in my conception of the book. And more than ever now it seems that the kingdom of heaven has to be taken by violence, or not at all. You have to push as hard as the age that pushes against you.

O’Connor is still read because her work keeps pushing hard against an increasingly materialist and relativistic age. A little over a hundred years ago, G. K. Chesterton complained, “We are on the road to producing a race of man too mentally modest to believe in the multiplication table.” He’s right. But there is nothing modest about O’Connor’s beliefs or assumptions about human nature, which is why her work is so provoking, challenging, and attacked.

Take her most widely-read work, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” This short story begins as a social comedy but ends as a profound look at the fallen human condition, a condition that can—according to O’Connor—only be rectified by the grace of God. The protagonist is a wholly unlikable grandmother whose selfishness and hypocrisy make it easy to feel superior to her: she’s stubborn, selfish, racist, lying, loudmouthed, and notably bad under pressure. She prattles on about how things were better when she was young and only knows “Jesus” as a curse; she’s a type more than a real person. But through a series of mishaps, all caused by her, she and her family meet the Misfit, a serial killer whose henchmen murder her son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren. Left alone with the Misfit, she hysterically urges him to pray in an attempt to appeal to his “good blood” and save her own skin. He isn’t interested. But before she dies, the grandmother reaches out to touch the killer in what at first glance is a moment of mistaken identity (the Misfit is wearing her son’s shirt) but which is also a mysterious gesture of forgiveness that strikes some readers as unrealistic only because it seems divinely inspired:

The grandmother’s head cleared for an instant. She saw the man’s face twisted close to her as if he were going to cry and she murmured, “Why, you're one of my babies. You're one of my own children!” She reached out and touched him on the shoulder. The Misfit sprang back as if a snake had bitten him and shot her three times through the chest.

This is O’Connor's most dramatic depiction of grace, the moment when God nudges a person closer to Him, an idea O’Connor saw as her greatest theme. “All my stories,” she remarked, “are about the action of Grace on a character who is not very willing to support it.”

The grandmother’s grace at gunpoint provokes us into considering the meaning of her death, a meaning perfectly articulated by the Misfit: “She would have been a good woman,” he explains, “if it had been someone there to shoot her every minute of her life.” In other words, her imminent death caused a change in her priorities—a clear head, as O’Connor tells us—and she dies a better person than she had lived. Her lying “with her legs crossed under her like a child’s” and her face “smiling up at the cloudless sky” suggests the innocence she seems to have found. She moves from the most selfish person on the syllabus to one of the most Christlike figures in the canon.

And there but for the grace of God go we. The Misfit’s eulogy of the grandmother also applies to the reader. We would all be better people if someone were pointing a gun at us. The line at Starbucks would no longer seem so annoying, what your sister-in-law said to you six Thanksgivings ago would no longer trigger a monologue to your spouse, and your inflated sense of importance might shrink to a manageable level. That’s what grace is for: as O’Connor wrote elsewhere, “Grace, to the Catholic way of thinking, can and does use as its medium the imperfect, purely human, and even hypocritical.” As for why this moment is not powerful enough to stop the Misfit, O’Connor had an answer for that, too: “It is the fact that the old lady’s gesture is the result of grace that makes it right that the Misfit shoot her. Grace is never received warmly. Always a recoil, or so I think.”

While readers who don’t care for O’Connor aren’t about to become wandering killers, they still balk at the fact that she takes an idea like grace as seriously as she does. There’s always a recoil.

I often challenged first-time readers of O’Connor to name which of her characters they resemble most. Even the most supercilious students paused when asked to do this. What happens during that pause is one of the major reasons why O’Connor is worth reading. This exercise is easy to do if you’re discussing Hamlet. Readers identify with (or empathize with, to use the contemporary cant) the troubled prince because, at some point, all of our worlds resemble his unweeded garden. They delight in his scorn of everyone else in Denmark because, at some point, we all scorn the people in our own worlds. To scorn is to show one’s superiority. And who doesn’t want to be seen as troubled because of serious matters, able to see through others’ hypocrisy, and able to speak with such intelligence, poetry, and meaning?

But who among us will admit to resembling Julian, the failed writer in “Everything That Rises Must Converge,” who lectures his elderly mother (after a person, not a book, has delivered a blow to her head) that she “got what she deserved?” Or Hulga Hopewell, who assumes she knows better than “good country people” and finds that her entire view of the world is as hollow as her wooden leg? Or Mr. Head, whose failings are so numerous that readers are as repulsed by him as the title of the story in which he appears? O’Connor’s characters exploit the weak, inflate their own importance, and commit acts of physical, emotional, and spiritual violence—and these aren’t even the villains. No readers rush to recognize themselves in these repulsive figures. Yet the staying power of great writing depends upon a reader seeing something of him or herself in characters as crazed as Captain Ahab or as evil as Iago. O’Connor’s characters still walk among us, still stare back at us from our bathroom mirrors, and still cause a stir. On the amount of repulsive figures and violent scenes in her work, she once replied, “To the hard of hearing you shout, and to the almost blind you draw large and startling pictures.” Startling as these pictures sometimes are, they reflect profound truths about the fallen human condition.

In story after story, she elicits a reaction from her readers and then uses that very reaction to make a larger point. O. E. Parker is a misguided hillbilly—until we understand why he is weeping at the end of “Parker’s Back.” The gathering at which Bevel is baptized in “The River” is a sham—until we think about why the child “knew immediately that this was not a joke.” Hazel Motes is strange, but at least he’s trying to warn people against con men like Hoover Shoates—until he has his road to Damascus moment and wraps himself in barbed wire to attone. Nobody does literary judo like Flannery O’Connor.

O'Connor unsympathetically asks readers to imagine God, the elephant in America’s living room, affecting regular, flawed people in mysterious, disturbing, and wholly unironic ways. She does not present God as a social construct, but as a force as real as gravity. There’s no hint of “just kidding” or cute ambiguity at the ends of her stories: when the fourteen-year-old protagonist of The Violent Bear It Away accepts—after committing a murder and then being violated—his vocation as a prophet, he knows that he will not have an easy time of it. He will not be honored by anyone and knows there’s a chance his head will be on the Tennessee equivalent to Salome’s dish. But he does know that his calling is real. He had to struggle, like O’Connor’s readers, to accept that such a thing could happen in the first place; in other words, he had to have faith. And this isn’t the feel-good faith of George Michael, but a different kind: in a 1959 letter, O’Connor wrote, “What people don’t realize is how much religion costs. They think faith is a big electric blanket, when of course it is the cross. It is much harder to believe than not to believe.”

But this does not mean that she avoids the arguments of the other side or operates as a literary Ned Flanders. Some of her most memorable and sympathetic characters are nonbelievers. In Wise Blood, Hazel Motes establishes The Church Without Christ to save his followers from the foolishness of such doctrine as justification: the transforming of a person from a state of sin to one of holiness, a transformation that, according to Christianity, only God can affect. “Nobody with a good car needs to be justified,” Hazel insists. George Rayber, the schoolteacher in The Violent Bear It Away, dismisses faith as a weakness and holds Bishop, his son with special needs, as proof of God’s nonexistence, which makes him the voice of rationality to many first-time readers. However, O’Connor reveals halfway through the book that Rayber once took his son to the beach and attempted to drown him—and, although he didn’t succeed, regards it as a “failure of nerve.” When students were shocked by this, I always feigned surprise, noting that Rayber’s actions are in perfect accord with his nihilism. If people are simply masses of molecules, why should one mass count for any more than another? If Bishop is, as his father sees him, a mistake, then why not correct it? O’Connor has been dead for just over sixty years, but her work shows that there is nothing new under the sun, including what many students see as a “modern,” enlightened deconstruction of Christianity.

Some readers falsely assume that O’Connor's aim is to “convert them,” an idea that O’Connor, a masterful writer but humble about her craft, would have found outrageous and an exaggeration of her powers. No novel or short story is ever going to make the crooked straight, nor is that fiction’s ultimate aim: in a 1956 letter, she dismissed a “religious” novel as “just propaganda” and added, “its being propaganda for the side of the angels only makes it worse. The novel is an art form and when you use it for anything other than art, you pervert it.”

But her fiction does have the power to yank us out of the world of social media and into one where we must confront issues as big as they come. In one of her stories, a woman complains about the way a child has put on his coat: “He ain’t fixed right.” O’Connor’s fiction provokes us into considering the degree to which any of us can be fixed right in a world without God or at least values that arise from clear definitions of good and evil. This isn’t an idea we always want to entertain, certainly not in a world where we often look to popular culture to help us feel great about ourselves: “I loved [fill in title of movie or book that treats an “important social issue”]. Aren’t I a good man?” A good man is hard to find. The old expression that one can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar is certainly true, but O’Connor knows that too much honey makes us flabby, both physically and morally. Her work has more vinegar than a reader may be used to: after all, this is a writer who remarked, “The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.” But the truths she explores extend beyond any theological doctrine: readers of all faiths, and of no faith, can find much to admire in her work because it reveals so many truths about human nature. This is why we read it.

I am in as much awe of O’Connor’s work as I was when I first stumbled upon it thirty years ago. I never went through a phase with her work as I did with other, also-impressive writers: like Johnson, Joyce, and Shakespeare, she has affected my vision of the world. And while her output isn’t as extensive as others’, it remains inexhaustible. My reward as one of her readers isn’t that I become a better person; the world is filled with terrible people who love to read. Anyone who thinks that reading O’Connor makes them a better Christian is missing the point of “Revelation,” in which Mrs. Turpin assumes she understands the will of God and organization of Heaven. The reward of reading O’Connor is that we are brought closer to a person of raw intelligence and insight into the human condition–the same reason we read the works of any great writer. O’Connor shows us why we ain’t fixed right but her fiction is not a set of instructions on how to make repairs. She knew, more than anyone, that there were other books for that.

I enjoyed reading this, you make many excellent points and I share your dismay at the students weilding their jargon - 'agency' and 'otherness'. Every single aspect of our lives has become politicised whilst humanist principles of reasoned enquiry have been abandoned. I'm considering doing A Year of Joseph Conrad after I've finished Jane Austen.

There's no one quite like her. A true master. Thanks for your reflections. Look forward to reading more of your stuff. New sub!