What Makes for Great Acting?

The Case of True Believer

Here’s a post based on an idea from this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics. We choose the films almost at random: one of us will watch (or rewatch) something and text the other guy. We then record without any previous conversation, recreating the enthusiastic conversations people have in the cars on the way home from the theater. We also take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over 250 and you can find them all here. No spoilers in this one.

What do we mean when we call someone a “great actor?” We heap praise upon people who convince us that they are—in that moment—a different person, despite our knowing that this is untrue. We say that Robert De Niro “inhabits the role” of Jake LaMotta or that Daniel Day Lewis “becomes” Daniel Plainview and are moved by their performances despite our never forgetting that we are watching someone say things that he had memorized and said in a way that has been rehearsed, coached, and finessed. None of that makes the illusion less powerful; when I watched Manchester by the Sea you could have sat next to me the whole time and whispered, “Casey Affleck is not Lee Chandler,” but that wouldn’t have mattered. It would have been irritating, but it wouldn’t diminish my admiration for what he does in that movie.

In his new memoir, Al Pacino describes this phenomenon of our knowing that actors are actors and still “believing” in what they are showing us:

The thing about acting is, you don't really do it and yet it’s real. That’s the phenomenon. That’s the paradox. We actors have to go through it to find it in ourselves, so we can paint it.

You don’t really do it and yet it’s real is about as good a way to put it as volumes of gobbledygook written about Stanislavski, Meisner, Adler, or the Method.

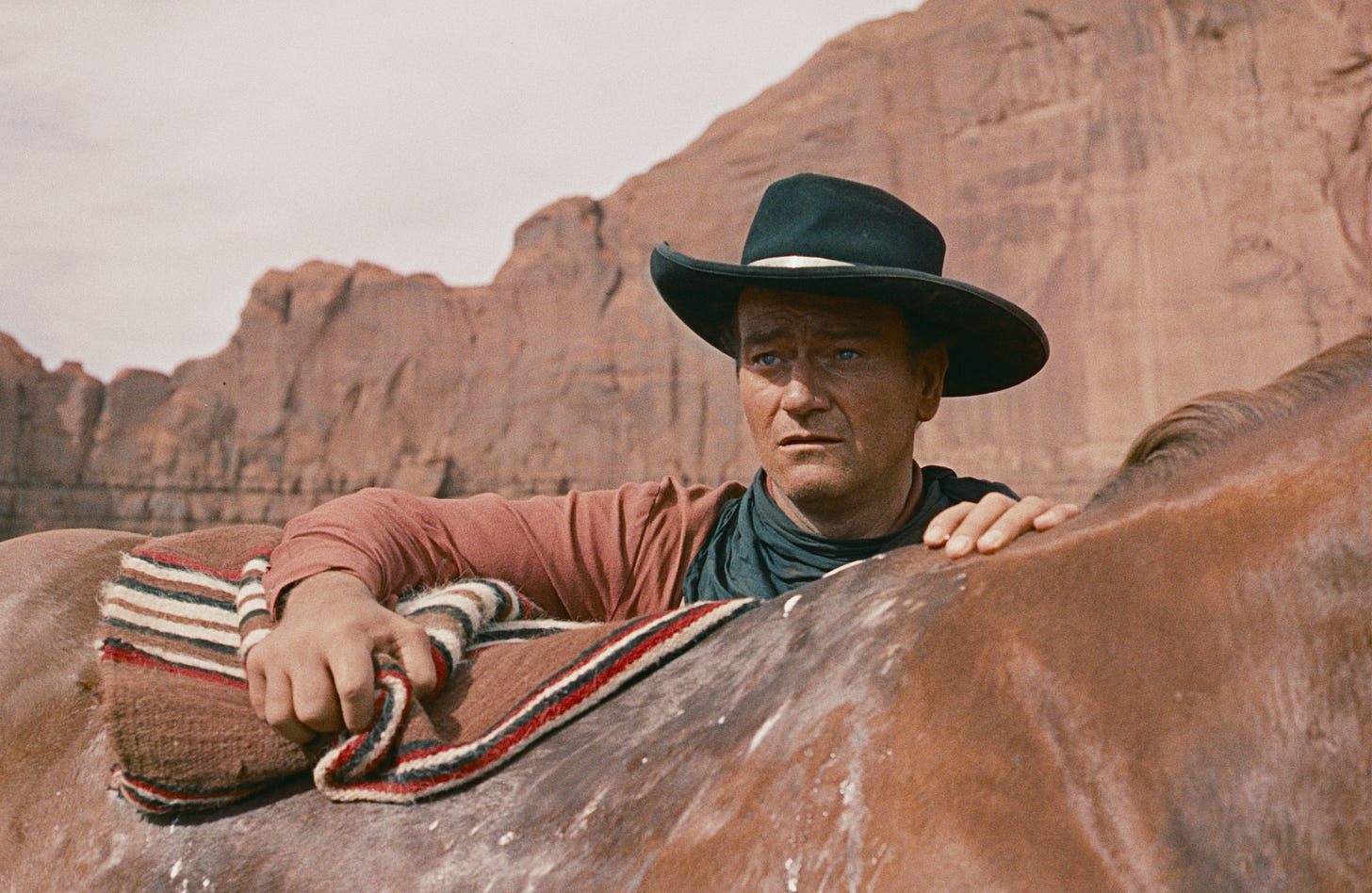

One of the greatest performances of all time is John Wayne as Ethan Edwards. I don’t know what Wayne “drew upon” to play Ethan, what “sense memory” he invoked or what “forms of transference” he employed. But I do know that there are few movies where the boundary between actor and character seem so blurred—“seem,” not “are”—that the performance is always arresting and there’s always something new in it to see.

But there’s another way to appreciate actors and why they engage us. In True Believer, James Woods may not deliver the most nuanced performance as Eddie Dodd; he’s more hammy than Pacino in The Devil’s Advocate. But he’s interesting and the viewer finds his manner of speaking worth the less-interesting aspects of the film, like whose bullet was in the corpse or even how Eddie Dodd will win the case (since we know that he will). When he tells his would-be killers that he won’t stop talking because he can’t, we hear James Woods more than Eddie Dodd, yet that doesn’t pull us out of the movie. People love Vincent Prince, Charlton Heston, and James Mason for the same reason: we like to hear them talk. (And before anyone cavils at my lumping James Mason in with the others, I’ll remind everyone that his voice is what we love most about him.)

One of the greatest film actors embodies both of these ways in which we can appreciate what actors do. In On the Waterfront, Marlon Brando and Terry Malloy bleed into each other at every moment. He doesn’t really do it, and yet it’s real. And I’m not thinking of only the justifiably-famous taxi scene, but of small moments that, like John Wayne’s in The Searchers, always reward us for paying attention: how he plays with Eva Marie Saint’s glove, how he reaches out with his left hand to gently touch Charlie’s shoulder when he finds him hanging from a hook, and how he tosses aside his half-eaten snack in the bar and mutters, “Comedian” to the insulting bartender. In The Godfather, we can similarly allow Brando’s more famous moments (“Look how they massacred my boy”) to stand as examples of his “becoming” Don Corleone, but also relish how he uses his hands when trying to calm the other dons at the meeting, how he patiently waits for Luca Brasi to finish his speech without making him feel stupid, or his response to Michael telling him that his son reads the funny papers. We can’t believe how perfect all of these moments are and they combine so well and with such strength that we surrender to the illusion. And that’s not the Method at work—Brando hated being associated with the Method. It’s the power of an imagination so rich that he could pretend to be a nonexistent person with that level of detail.

We can also appreciate Brando’s acting in this second way—call it the Woods way—in some of Brando’s less-successful films or downright stinkers. Désirée is not a film we eagerly seek to rewatch, but the scene in which he, as Napoleon, berates Bernadotte has the kinds of outbursts and pauses that at least hold us in those moments in an otherwise dull movie. We want to hear what he’ll say next. Reflections in a Golden Eye is a stew of psychobabble, yet his lecture to cadets about leadership grabs the viewer. The whole movie should be him doing a Teaching Company course as that character. And he was razzed for his performance as Jor-El, but does Russell Crowe do it any better? Who cares if Russell Crowe is more “convincing” as Superman’s father? Even in his preposterous getup, Brando is at least interesting.

There’s a third way to look at actors: to dismiss what they do altogether and stop lauding them or writing about them. When Samuel Johnson was teased by his biographer, James Boswell, because Johnson would “never allow merit to a player,” Johnson rolled his eyes (this is not in the text, but I know that he did) and launched into one of his impromptu Socratic seminars:

JOHNSON. 'Merit, Sir! what merit? Do you respect a rope-dancer, or a ballad-singer?' BOSWELL. 'No, Sir: but we respect a great player, as a man who can conceive lofty sentiments, and can express them gracefully.' JOHNSON. 'What, Sir, a fellow who claps a hump on his back, and a lump on his leg, and cries "I am Richard the Third"? Nay, Sir, a ballad-singer is a higher man, for he does two things; he repeats and he sings: there is both recitation and musick in his performance: the player only recites.' BOSWELL. 'My dear Sir! you may turn anything into ridicule. I allow, that a player of farce is not entitled to respect; he does a little thing: but he who can represent exalted characters, and touch the noblest passions, has very respectable powers; and mankind have agreed in admiring great talents for the stage. We must consider, too, that a great player does what very few are capable to do: his art is a very rare faculty. Who can repeat Hamlet's soliloquy, "To be, or not to be," as Garrick does it?' JOHNSON. 'Anybody may. Jemmy, there (a boy about eight years old, who was in the room) will do it as well in a week.' BOSWELL. 'No, no, Sir: and as a proof of the merit of great acting, and of the value which mankind set upon it, Garrick has got a hundred thousand pounds.' JOHNSON. 'Is getting a hundred thousand pounds a proof of excellence? That has been done by a scoundrel commissary.'

Of course, Pacino did clap a hump on his back and cry, “I am Richard the Third” and received more than the 1791 equivalent of a hundred thousand pounds. Is he any good as Richard? It depends on how you’re judging: if you’re using the traditional criteria, not really. Other Richards could defeat him long before he cried for a horse. But looking at him as a practitioner of the Woods way, he’s entertaining and you want to see what he does next.

And even if he saw Pacino in one of the greatest roles of his career—one of the greatest in the history of film—Johnson would never become a true believer.

Listen on the player above, on the New Books Network, or wherever you get podcasts.

Hi. This is very thoughtful and perceptive. Thank you.

I'd like to offer a few observations.

"The Method." As you indicate, Brando didn't espouse it. When many people (not including you) talk about the Method, they are referring to a very general shift in the approach to acting that took off after the war. The real beginning, I suppose, was Stanislavsky's Moscow Art Theatre and his theories of acting, which inspired the members of The Group Theatre. But the Method itself was theorized, taught and practiced by Lee Strasberg, and it was based on his particular interpretation of Stanislavsky. Stella Adler visited Stanislavsky in Paris, he told her he'd revised his theories, and she left the Group, broke with Strasberg and started her own studio. So did Sanford Meisner. I think Kazan had the right idea - that there were positives and negatives in all their approaches, but that in the end what mattered most was the work itself.

As an aside, when it comes to acting teachers, not enough attention has been paid to Viola Spolin and the whole tradition of improv that grew out of her work (Sam Wasson's great book IMPROV NATION is a must read). Secondly, there's Jeff Corey, who started his own acting school out of his house when he was blacklisted in the 50s. Among many other people, Jack Nicholson trained with Corey, along with many, many others, including Robert Towne and Sally Kellerman.

I think there are many performances that are so quietly concentrated that they go unnoticed and unremembered. They are not the kinds of performances that win awards or raves. You mentioned John Wayne in THE SEARCHERS and rightfully so. And he's just as great in RIO BRAVO, in a completely different key - just watch him riffling his way through a deck of cards as he talks to Ward Bond. Anthony Edwards in ZODIAC - a remarkable performance, and Elias Koteas is just as good in the same movie. De Niro and Duvall in TRUE CONFESSIONS. Cristin Milioti in THE WOLF OF WALL STREET. The actor who plays the husband in DOUBLE INDEMNITY. Greta Lee in PAST LIVES. Richard Farnsworth in COMES A HORSEMAN. G.D. Spradlin in anything…And as great as everyone is in JACKIE BROWN (possibly the best film that director will ever make), as much as I love Pam Grier and Samuel L. Jackson and Bridget Fonda and De Niro in the film, I think that Robert Forster gives one of the finest performances I've ever seen - not one false moment.

I’d be curious to hear your thoughts on ‘bad acting’ too — and how much of this is purely subjective. Surely you’ve watched a wildly praised performance and thought, “Wait - but this is awful!”