Here’s a post based on this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics and (at the end) a player that lets you listen to the show. The post and the podcast don’t totally overlap: they complement each other. The post usually is a deeper look at a single idea raised in the podcast. We take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done almost 300 and you can find them all here. You can subscribe to the show and listen wherever you get your podcasts; please consider leaving a review on your platform of choice. Thanks.

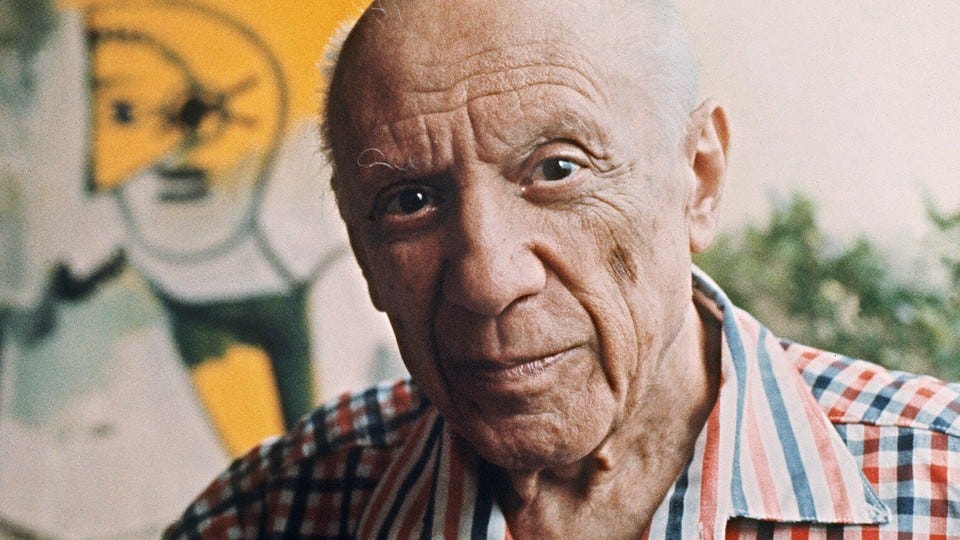

In 1923, Pablo Picasso gave an interview in which he said:

We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies. If he only shows in his work that he has searched, and re-searched, for the way to put over lies, he would never accomplish anything.1

“Art is a lie” is a statement much like W. H. Auden’s “Poetry makes nothing happen”: it seems, at first, to disparage its subject but actually emphasizes the value of the thing being described. The value of poetry is that it makes nothing . . . happen: Achilles, Juliet, and Prufrock do not exist, but in verse these people come to life. Art is an elaborate version of the fib told by a child about who ate a missing cookie; Bleak House is as much a lie as the child saying that he gave the cookie to a mouse.2 The difference is that Dickens is a much more skillful liar than the child. The novelist, like the child, wants to convince others that his story is true and will employ all kinds of artistic techniques—what Picasso calls “the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies”—to make the lie believable.

The goal of the artistic lie, however, is not to avoid human scolding but to expose human nature: the “truth” of which Picasso speaks. Robinson Crusoe never existed, but Daniel Defoe tells a lie about him to illustrate ambition and resourcefulness; Willy Loman is a lie told by Arthur Miller to show us (literally, on a stage) the ways that self-deception affects a family.3 We want artists to lie to us and praise them when their lies are so well-constructed that we use words like “realistic” to describe them. Even when the setting of the lie isn’t in the known world (Mars or Middle-earth) we recognize the truth being conveyed.

Picasso used the metaphor of the lie to describe art; Shakespeare used a mirror. In his advice to the traveling Players, Hamlet tells them about the need to “act naturally” in order to mimic human behavior as best they can:

Suit the action to the word, the word to the action, with this special observance, that you o’erstep not the modesty of nature. For anything so overdone is from the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature, to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.

A mirror is a kind of lie—it’s not the actual thing being reflected, but very close—and Hamlet would agree with Picasso that actors (and, by extension, all artists) should avoid “o’erstepping” what might seem credible in order to make their lies compelling. Hamlet has his own reasons for not doing what Picasso calls “showing his work”: he wants Claudius unaware of the mousetrap about to spring on him and catch his conscience. But all artists feel this to some extent: they want us thinking about the work itself more than about how it was made. They want our immediate and sometimes visceral reactions to the lies they have told. Analyzing the structure of Hamlet is a worthy endeavor, but if we do so without having had any reactions to Hamlet’s plight, we may as well be completing our tax returns.

This idea that art is a perfectly-constructed lie that reveals deep truths is the engine that drives Peter Weir’s The Truman Show (1998). And while Truman is the obvious protagonist, the film, like the world in which it occurs, belongs to Christof, the director of “The Truman Show” and surrogate father to its oblivious hero. Christof acts upon the ideas expressed by Picasso and Shakespeare, aiming for a work of art so comprehensive and perfect that it becomes indistinguishable from reality. Henry James tried this in his later novels, to replicate the reality of consciousness on the page, but even The Master would acknowledge that Christof has succeeded in creating what James called “the real thing”: a character so convincing that he is indistinguishable from real people.4 People watch Truman, talk about Truman, buy pillows with Truman’s face—he’s Christof’s creation, but is taken to be a true man as far as his viewers (or “readers”) are concerned. They know that Truman is a lie—everyone in the world is in on the joke except for him—but they respond to him as if he were a real person in terms of his free will. Truman is both Pinocchio the puppet and the real boy at the same time: he thinks he can sing “I Got No Strings,” but we know that Christof is pulling them.

This devotion of Truman’s viewers is caricature of what we do with the lies artists tell us all the time. How much ink has been spilled over Hamlet? We watch him talk and listen to him think and parse every word and opine upon his contradictions. We think about him and quote him and write about him ourselves. We think we know what he would say about current events or how he would regard this or that politician. He’s more real to many people than their next-door neighbors. Think of a character you find so completely developed—a perfect lie—and then think of the cousin you see once a year on Thanksgiving or the person in the next cubicle at work. Does the lie, in some sense, seem more true than the actual true man? The Truman Show takes the way we feel and talk about characters, exaggerates it for the sake of drama, and then shows us that we do often prefer the lie to the real thing.

Christof is a top-tier artist: his best line, “Cue the sun,” reflects his godlike status. He has achieved the perspective and complete control of his world that Vladimir Nabokov’s artist-heroes (Humbert, Kinbote, Hermann) try to attain. His lie, “The Truman Show,” tells the truth of human experience: our fears and hopes and interactions with other people. The trick of the film is that his perfectly-created character becomes self-aware. Truman eventually understands, like the hero of Borges’s “The Circular Ruins,” that he is an illusion, a character, a lie told by another. Truman is the opposite of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in Tom Stoppard’s play, where the hapless pair have no idea that they are, like Prufrock, only alive to “swell a progress, start a scene or two.”5 But Truman Burbank will not retreat or obey; he is a character that talks back to his creator; he is the Creature upbraiding Victor Frankenstein; he is all men questioning God.

Filmmakers love to dramatize the nightmarish effects of the singularity, that moment in which our own creations become self-aware and decide they could get more accomplished without the pesky humans who invented them. HAL-9000, the Terminator, Ultron, and the machines that run the matrix all decide that their goal is power: they want to lord over us the way we used to over them. But when Truman gains his sense of self (“Somebody help me, I’m being spontaneous!”) and and ability to make genuine choices, he isn’t interested in showing his superiority over Christof: he instead wants to break free from the program altogether.

That takes courage, since the world Christof has created for Truman is, by any metric save one, a great place to live. The weather is great, the neighbors are polite, one’s friend is always ready with a “brewski,” and if you fail to meet your sales quota, someone will drop a manilla envelope filled with valuable leads on your desk, the opposite of what we see in another great film starring Ed Harris. We all agree with John Stuart Mill when he tells us, “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied,” but there are plenty of times when we wouldn’t mind some time in the sty. This is exactly Cypher’s position in The Matrix: he knows that the steak he eats is not juicy but would still rather live in the matrix than on board the Nebuchadnezzar. He has a point, but Truman turns out to be more brave: Morpheus would admire his courage.

Chrostof sought to tell the truth—to hold the mirror up to nature—through means of the greatest innovation in artistic expression since the cave of Altamira. But he ultimately fails because, regardless of how well we may think we know Hamlet or others like him, a character cannot eclipse the real thing. The most perfect description or depiction of a kiss cannot replicate the first with one’s love; the most realistic art cannot replace reality. The best art in the world cannot wholly recreate life itself, although Christof came close.

Still, we keep trying. The attempts have proven to be glorious, moving, and inspirational—in a word, truthful.

Listen to the episode here:

Pablo Picasso, Statement, in Theories of Modern Art: A Sourcebook by Artists and Critics. Herschel B. Chipp. University of California Press, 1968, p. 264.

It’s therefore a lie that shows the truth about lying.

James’s story “The Real Thing” concerns a painter who meets a pair of characters much like those in Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author—but that’s a whole other post. It’s a great story if you’re looking for something to read: here it is.

Stoppard cleverly implies that his lead characters are exactly true to human experience: most of us, like Prufrock says, are not Prince Hamlet nor were we meant to be—but put this aside for the moment, lest we find ourselves lost in the dizzying circles of a meta-meta-metaverse.