Here’s a post about this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics. We choose the films almost at random: one of us will watch (or rewatch) something and text the other guy. We then record without any previous conversation, recreating the enthusiastic conversations people have in their cars on the way home from the theater. We also take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over 250 and you can find them all here. Spoilers always abound.

In a recent survey of American voters, 47% of those polled said they found it “easy” to “determine what is true and what is not” in terms of news about the 2024 elections.

This does not mean that the 47% are actually able to make these determinations; it means that 47% of those polled think they are good at separating the signals from the noise.1

Anyone can fake anything and present it as the truth and when that truth concerns a candidate for high office, the phrase “keeping it real” can take on a sinister tone. That’s the premise of Blow Out, Brian DePalma’s 1981 thriller: a wonderful downer that has finally, with the help of one of DePalma’s most notable fans, found an audience.

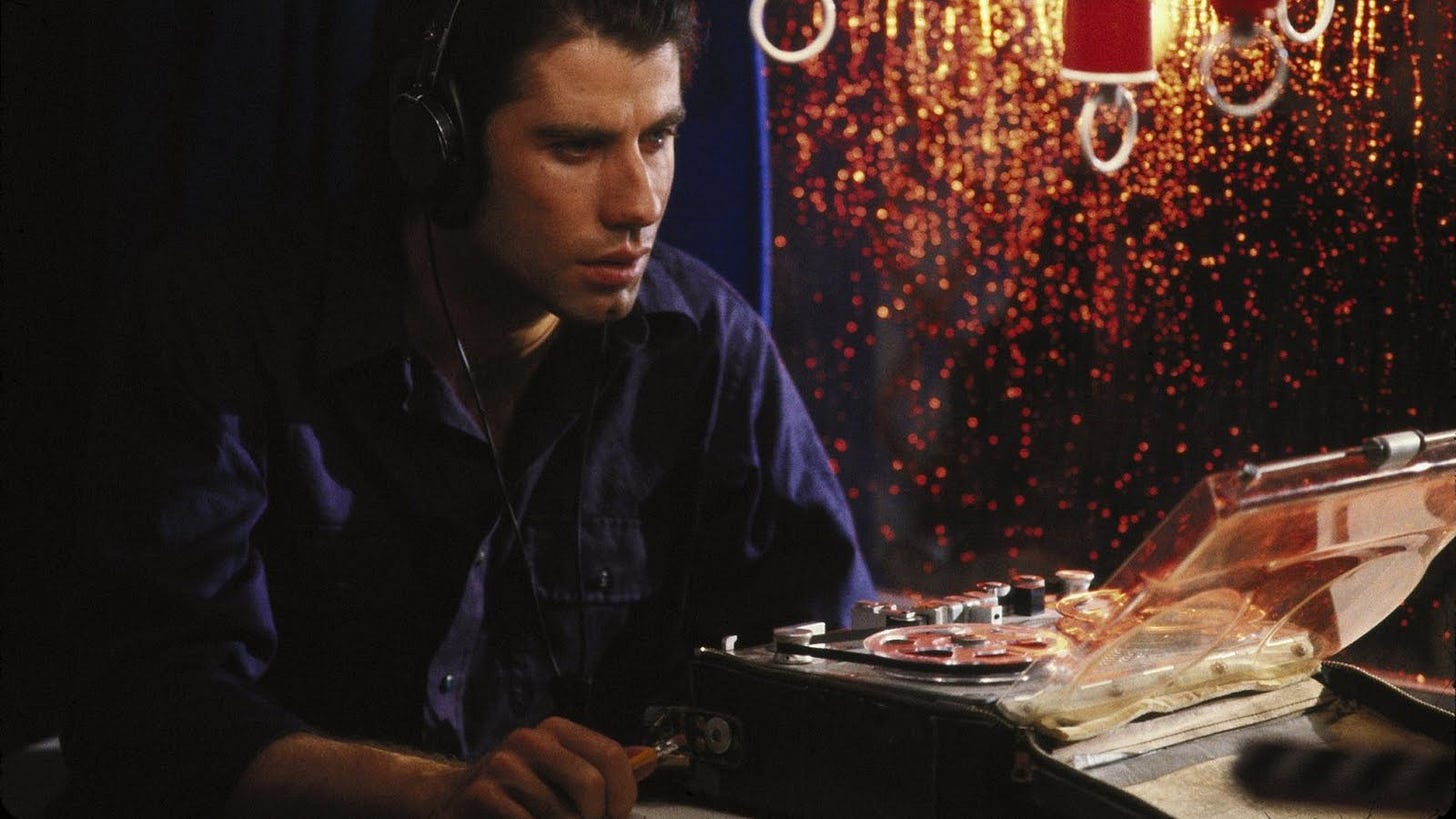

Jack (John Travolta) is a sound engineer who, like his colleagues in studios across the country, knows that the sound must reflect the sense. If a scene takes place in the woods, there should be ambient “woods sounds” that add to the realism. Hamlet said actors should suit the action to the word; Jack has to suit the sound to the image. DePalma introduces this aspect of Jack’s job early in the film, when we see a would-be slasher’s victim—a sleazier Marion Crane—scream in a voice that breaks the tension because it doesn’t sound authentic. As a sound engineer, Jack cares about fidelity, which he learns is an interesting concept when discussing our elected officials.

Blow Out resembles other conspiracy films in which the hero stumbles upon a web spun by bigger forces that operate out of the reach of headlines or other forms of daylight. His uncovering the conspiracy is the thrill of the movie: at least one supporting character will tell him to stop for his own good and another will warn him, “You have no idea how high this goes.” But he persists and uncovers the truth, either to the audience’s applause (All the President’s Men) or exhaustion (The Manchurian Candidate). Other genres rely on the same framework: Neo in The Matrix uncovers the Big Lie and we are exhilarated and excited by the idea that he’ll be out there fighting the machine (although we are less excited by the sequels) while in Chinatown, Jake Gittes learns about how the water flows in L. A. and a terrible secret about a power broker, but is unable to do anything about either one. Nobody will listen and, really, nobody cares.

Jack is more Jake than he is Neo. He sees how the sausage of democracy is made and is worse off for it.

Blow Out is a collage of American conspiracies: we get Chappaquiddick, the grassy knoll, a potentially-embarrassing escort, wiretaps, and a stand-in for G. Gordon Liddy. And in the best shot of DePalma’s career, we see Nancy Allen screaming in front of an American flag in the City of Brotherly Love. We’re told America runs on Dunkin’, but its real fuel is what happens in the shadows.

At the end of the film, Jack finally pleases his director by finding the right scream: a real one, recorded before the woman who made it was murdered. That doesn’t make sense in terms of the character—why would Jack use the actual dying scream of a real person, one for whose death he feels responsible, for a cheap slasher film? It’s sadistic and grotesque and Jack’s absolute decency is what makes him pursue the truth. But DePalma couldn’t resist presenting the idea that the line between reality and falsehood is impossible to detect. The audience of Jack’s movie will never know that the scream has been dubbed, let alone its actual source. The public will never learn the truth about the car accident and “know” there was a blow out instead of a gunshot. When the director compliments him on his audio work with, “Some scream!” Jack says, “Yeah—some scream.” And since they are all sitting in the dark looking at the rough cut, the director—who cannot see Jack’s face—thinks he is nodding in agreement, when we know that he is holding back tears.

You can’t believe everything you hear—a statement to which Harry Caul in the other great sound-guy-conspiracy film would agree.

James Ellroy prefaces his 1995 novel American Tabloid, a symphony of conspiracies involving Howard Hughes, the FBI, JFK, J. Edgar Hoover, the CIA, Cuba, and communists, with this declaration:

America was never innocent. We popped our cherry on the boat over and looked back with no regrets. You can't ascribe our fall from grace to any single event or set of circumstances. You can't lose what you lacked at conception.

Mass-market nostalgia gets you hopped up for a past that never existed. Hagiography sanctifies shuck-and-jive politicians and reinvents their expedient gestures as moments of great moral weight. Our continuing narrative line is blurred past truth and hindsight. Only a reckless verisimilitude can set that line straight.

Whether or not Blow Out sets anything straight is debatable. One might see it as a statement about the worm in the apple that was baked into the American pie; one might regard DePalma as someone uninterested in big ideas and enjoy Blow Out the way one enjoys his other entertainments, such as Dressed to Kill, Mission: Impossible and The Untouchables. Either way, in at least the world of the movie, what’s real and fake has become impossible for people to separate, regardless of how highly they rate their own acumen when they respond to a pollster. The one person who knows the truth sits crying in the dark.

Listen on the player above, on the New Books Network, or wherever you get podcasts.

A few days ago, someone showed me a group photo in which two figures, absent at the time of the photo, were digitally inserted. When I complimented the photographer on what a good job he did with his digital trickery, he told me he did it with MS Paint. Not Lightroom or DxO—but MS Paint, the least sexy imaging software which many of us last used decades ago when we were kids and fascinated by desktop computers.