Bring the Big Heat

Fritz Lang and Herman Melville

Here’s a post based on this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics and a link to the ad-free version of the show. We choose the films almost at random: one of us will watch (or rewatch) something and text the other guy. We then record without any previous conversation, recreating the enthusiastic conversations people have in their cars on the way home from the theater. We also take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over 275 and you can find them all here. You can subscribe to the show wherever you get your podcasts; please consider leaving a review on your platform of choice. Thanks.

One of my longstanding complaints about horror movies is that characters are rarely sufficiently afraid. Aside from Ellen Burstyn, Shelley Duvall, David Naughton, and Heather Donahue, the actors always come across as a shade too brave or (worse) defiant in the face of supernatural forces. (The kids in It might be Exhibit A: they are as nervous about facing the sewer-dwelling demon as the members of Mystery Incorporated.)

There’s a similar phenomenon in movies about crime fighters: after confronting whatever depravity the plot shoves in their faces, they end pretty much the same as they began: they hang up their holsters and the credits roll. At the end of The Maltese Falcon, Spade tells Brigid he’ll have a few bad nights, but he’ll get over her—and we know he will. But Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) is, like Chinatown and No Country for Old Men, a wonderful exception. Sgt. Steve Bannion (Glenn Ford) takes on mob chief Mike Lagana (Alexander Scourby) and his cronies in and out of the department, but he has to suffer in the process and, while victorious, is not the same person he was in the beginning. We don’t see this coming.

The script followed by everyone in the film’s fictional city of Kenport is that Lagana runs everything and the police brass serve at his pleasure. From the Police Commissioner and Lt. Wilks to Lagana’s thugs Larry Gordon and Vince Stone (Lee Marvin) to Stone’s girlfriend Debby Marsh (Gloria Grahame), everyone goes along with the script because it’s easier and safer to do so than to ad-lib and think for oneself. Say your lines and stay in your lane and everything will be fine. But this order is artificial and propped up only out of the tacit agreement that it’s better to live as a sheep than die as a fox. As Tom (Gabriel Byrne) tells his mob boss Leo (Albert Finney) in Miller’s Crossing, “You don't hold elected office in this town. You run it because people think you do. They stop thinking it, you stop running it.” The script that Lagana has imposed upon Kenport hangs by a thread—and a threat, since anyone who tries to upset it will find himself in need of a doctor or mortician.

But just as it would take only one actor not knowing his lines to ruin a play, one cop not knowing his can ruin an entire syndicate and Lang shows us just how artificial this script is when Bannion enters the drama. Called a “natural corn-treader,” he refuses to play to his expected role or go along with the hypocrisy that keeps everything humming. Early in the film, he reminds his wife, Katie (Jocelyn Brando1), that a child-rearing book says that they should be “patient but firm” with their daughter. That’s how he fights crime and it’s worked well for him, until he double-checks the suicide of a fellow officer who turned out to be more like a cop in a James Ellroy novel than a Jack Webb teleplay.

After he begins investigating that suicide, the filth Bannion has sworn to clean enters his house. Lang gives us long scenes of Bannion and Katie making dinner, joking about their daughter’s refusal to go to bed, and living the American dream. She takes a drag from his cigarette and sips from his glass; they look at each other like cow-eyed teenagers.

Anyone seeing this out of context would think Bannion was an actuary or professor; the only hint that he’s a cop is the easy-to-miss photograph of his graduation from the police academy hanging in the foyer. But when one of Lagana’s hoods calls Bannion’s house and lets out a stream of four-letter-words to Katie about the need for her husband to lay off, the door separating his home from the street has been cracked open; when Bannion refuses to step down, the door is blown off its hinges like the car that explodes when Katie turns the key. A man’s home is not his castle; it can be invaded and defiled, which is why after Katie’s death we get the scene of Bannion standing in his empty living room. He brought his work home with him and feels responsible for what it did to his family. We don't blame him, but he blames himself and that blame is what propels what another cop calls his “hate binge” against Lagana and all of his minions. He loses his badge but not his desire to do with Kenport what he did with his daughter’s house of blocks.

Bannion’s nemesis thinks the same way, but the viewer and Bannion sees through his hypocrisy. When Bannion enters Lagana’s house, he has to sit through the criminal’s lecture about his mother, whose portrait hovers over the scene. Mom’s always watching! When Bannion tells Lagana that he’s there to investigate him, Lagana says, “This is my home—and I don’t like dirt tracked into it.” He pretends to have the moral high ground, but, again, everybody knows that he is the source of all the dirt.

As we follow Bannion’s binge, we approve of his methods, badge or no badge. Who wouldn’t want to see someone as charismatic as Glenn Ford take apart Lee Marvin, who burns a woman with a cigarette after she beats him at dice or throws a pot of scalding coffee into his girlfriend’s face? We’ve seen this movie before—the hero moving through hoodlums with wisecracks and fists—until the screenwriters Sydney Boehm and William P. McGivern insert a moment in which Bannion confronts Bertha Duncan (Jeanette Nolan), the ice-cold widow of the morally-tortured cop who killed himself in the opening scene. Bannion figures out that she is responsible for the loss of his wife, job, and sanity, and he begins to talk himself into killing her for what she did and the good it would do for the world:

BERTHA: The coming years are going to be fine, Mr. Bannion.

BANNION: There aren’t going to be any coming years for you. None at all.

BERTHA: I don’t threaten easily.

BANNION pulls her out of her chair and shakes her.

BANNION: If anything happens to you, the evidence comes out. That’s the way you arranged it, didn’t you, bright lady? You got it all put away someplace. That’s how you kept Lagana over a barrel.

BANNION throws her against the wall and puts his hands around her neck.

BANNION: But I’m not Lagana. With you dead, the big heat follows. The big heat for Lagana, for Stone, and for all the rest of the lice.

Before he can finish, two patrolmen enter the house (deus a vigilum) and Bannion and Bertha pretend nothing is happening. Bannon, however, cannot forget what he almost did and what he learned he was capable of doing.

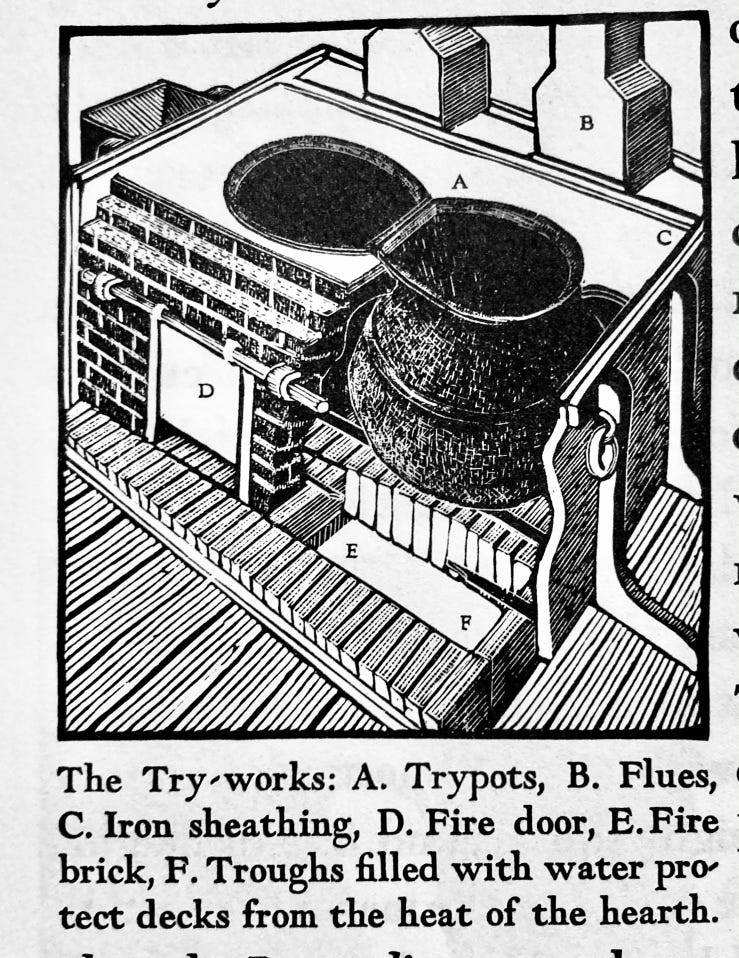

In “The Try-Works,” one of the how-whalers-work chapters of Moby-Dick, Ishmael tells the reader about a time when, after falling asleep on his feet and starting awake, he found himself facing the wrong way and almost slipped into the boiling vat of whale oil. He was able to pull back, but just in time. Like every other aspect of whaling, the try-works are also the source of introspection and metaphor: Ishmael knows what almost happened to him physically is what happened to Ahab morally. “Give not thyself up, then, to fire, lest it invert thee, deaden thee; as for the time it did me,” he advises. After the scene with Bertha, Bannion tells Debby (whom he now cares for in a new domestic space, a hotel decorated in what she calls “early nothing”), “I almost killed her an hour ago … I should’ve.” She shakes her head and says, “I don’t believe you could. If you had, there wouldn’t be much difference between you and Vince Stone.” She’s right, of course, but Bannion has, like Ishmael in Moby-Dick, peered into hell and narrowly pulled himself out. Because of what he has learned about the power of the evil he now has what Ishmael calls “a wisdom that is woe” and luckily avoids the descent into the “woe that is madness.”

Another analogy makes the same point: in Heart of Darkness, Marlow says that Kurtz “had made that last stride, he had stepped over the edge, while I had been permitted to draw back my hesitating foot.” Ahab and Kurtz went to the place where Bannion was headed as he put his hands around Bertha Duncan’s neck. He came back from the edge; they didn’t.

The Big Heat ends with order restored and things running as they should, with Lagana’s script replaced by one more ethical. The Big Heat that Bannion has stoked has burned away the lice—and, while heat is destructive, it’s also purifying. The shades of moral grey we expect in noir are gone: there’s only black and white. Bannion is back on the force, nameplate on his desk, and takes a call to investigate a hit-and-run. “Keep the coffee hot, Hugo,” he tells a patrolman as he leaves the squadroom. His house and home have been destroyed—that’s the cost he has paid—but he earns our admiration for protecting other people’s.

Yes, that Brando’s sister.

This is an outstanding essay! Easily the best analysis I’ve read of the film. And I loved the podcast. Yet another excellent discussion, brimming with insightful commentary. Great job!

Great discussion..saw this with "Human Desire" in the late 90's at tge Film Forum. Gloria Grahame was smoking hot in both..The latter is based on a Zola novel..I have Germinal gathering dust at home.You ever watch the Depardue film version ?