(You can hear the audio above or wherever you get podcasts. Scroll down for the video version, filled with stills from the films and our many hand gestures.)

Γνῶθι σαυτόν (“Know thyself.”)–The Delphic Oracle

Here’s a thought experiment: imagine a pie graph titled “SELF KNOWLEDGE” that shows you how much of yourself you truly understand, as opposed to how much you think you do. Perhaps it shows, in a charitable estimate, that you understand 75% of yourself. What if you could meet someone who would lead you through a series of events during which you learned that missing 25%? You would find out what you are capable of, what you really desire but try to hide from yourself, and what you wish you had the freedom to do. All of the lies you tell yourself about yourself would vanish.

Would you want it? Why or why not? And what would happen to you if you decided to go ahead and learn about yourself to that extent?

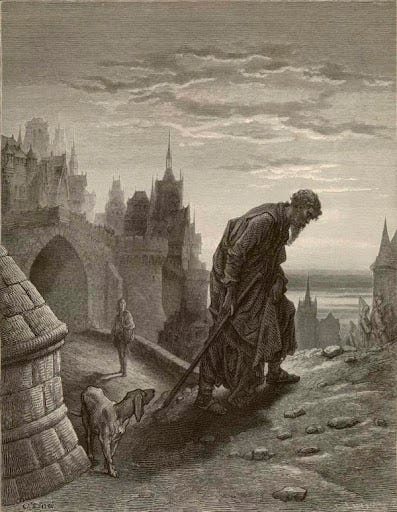

That 25% is the terra incognita that Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Alfred Hitchcock explore. Some of their best work allows us to accompany people who move into that dangerous zone. In Strangers on a Train, Guy Haines is confident in who he is—the tennis pro courting a senator’s daughter—and humors the seemingly harmless Bruno Antony about his silly “criss-cross” idea. Vertigo’s Scottie Ferguson tells Gavin Ulster that anyone who would think that the dead can possess the living needs to see “the nearest psychiatrist, or psychologist, or neurologist, or psycho—or maybe just the plain family doctor!” In Psycho, Marion Crane thinks Norman Bates has a kind of simple domesticity and innocence that she finds comforting. In The Birds, Melanie Daniels thinks that the world is a playground in which she can throw on her mink and toy with a man through a pair of lovebirds. The Ancient Mariner knows himself until his ship moves “below the kirk, / Below the hill, / Below the lighthouse top.” And “The lovely lady, Christabel, / Whom her father loves so well” spends her nights praying for “her own betrothed knight,” like the girl in a Tom Petty song.

All of these people think they are in their finished forms and when they find themselves in some sort of crisis, they are confident that they can make their crooked selves straight. But Guy learns that there’s a part of him that is capable, even momentarily, of acting like Bruno. Scottie ends up acting like the villain he never suspects, insisting that a woman transform herself into another. Melanie Daniels is traumatized by an attack of the cute creatures she assumed were there to amuse her. The Ancient Mariner commits a wonton act of unexplained, spiteful violence, Christabel finds herself in the orbit of an alluring yet vampyric photo-negative of herself—and we all know what happens to Marion Crane.

In this episode, I talk to Eric G. Wilson, author and professor of British Romanticism at Wake Forest University, about this fruitful pairing of a writer and filmmaker. When I first asked him what he wanted to discuss, he replied, “Coleridge and Hitchcock” almost instantly. Both of these artists were, in Eric’s words, “obsessed with obsession” and the work of each one illuminates the other’s. “Coleridge is like a proto-Freudian or proto-Hitchcock,” Eric says. “His work has the doubling and obsessions that show up all the time in the twentieth century. He’s the perfect writer to shed light on Hitchcock as a filmmaker.”

As for the pie chart, Eric answers that question with a joke: “When I was in college, I’d read Nietzsche all the time, where Nietzsche would talk about traditional thought and Christianity being all about getting a good night’s sleep and I was like, ‘Yeah! It’s so weak-minded!’ and now I’m like, ‘That sounds pretty good.’” But the joke points to a deeper truth that complete self-understanding and learning the things of which we are capable could push us into psychological danger or ruin. The doppelgangers in Hitchcock’s and Coleridge’s work illuminate the struggles and desires of the protagonists, but never their best qualities. Scottie never becomes (in the contemporary, nauseating phrase) the best version of himself and the possible awakening that Christabel may experience might also be moral poison. The Ancient Mariner ends “A sadder and a wiser man,” but the cost of that wisdom—life as an outcast, roaming around the world telling his story—is terribly high.

Tom Waits said you're innocent when you dream, but that innocence gets corrupted quickly in these movies and poems. The characters’ dreams are the ones you won’t have if you stay in the 75%. On his first album, Robert Earl Keen included a song which sets Christabel in Texas; its chorus is, “Things ain’t never what they seem / When you find you’re livin’ in your own dream.” When Coleridge’s and Hitchcock’s characters enter their own dreams, they are shaken and sometimes destroyed.

Do you really want to ride that carousel with Bruno? He’ll always be there at the carnival, waiting, but you may want to not buy the ticket.

I first met Eric G. Wilson when I interviewed him on the New Books Network about his study of John Boorman’s Point Blank. He’s a great conversationalist and his enthusiasm and deep reading makes for the kind of old-school conversation about books and film that I remember from my best classes. You can find my other conversations with Eric on the New Books Network and on Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics.