You can listen to the interview in the player above or wherever you get podcasts. You can also watch the video version by scrolling down to the player.

If you ever see Tom Lutz on Jeopardy! and the Final Jeopardy category is, “The Year 1925,” call Vegas and put your life’s savings, house, and 401(k) on his winning the game.

His new book, 1925: A Literary Encyclopedia (Rare Bird Books), is an exhaustive collection of entries on the cultural, scientific, and historical scenes; across 800 pages, entries range from “Wilbur Cortez Abbott’s The New Barbarians” to “Zeitgeist.” The philological coincidence that makes that word the last entry is perfect for the book, which captures the spirit of its time in a manner that is accessible, erudite, and addicting. As a novelist, historian, professor, critic, and founder of the Los Angeles Review of Books, Lutz has lived among books his entire life, but he is far from bookish: like his writing, he’s energetic, often funny, and engaging.

When I asked him the obvious question, “Why 1925,” he said that it was “arguably the single most astounding year in American literary history.” It saw the most important work of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Dreiser, Dos Passos, Cather, Gertrude Stein, H. L. Mencken, and Sinclair Lewis, as well as the first stories of Faulkner, the start of the Harlem Renaissance, the first collection of T. S. Eliot’s poems and drafts of Ezra Pound’s Cantos, the first novel by a Native American woman, and the founding of The New Yorker. Also percolating in the 1925 pot were Heisenberg’s first papers on quantum mechanics, the first TV transmissions, motels, in-flight movies, and trade magazines for the plastics industry, long before this became a joke in The Graduate. The year saw the birth of the blues, art deco, surrealism and the Scopes Trial, Sacco and Vanzetti, and, overseas, more literary innovation and the first lights of the coming nightmare in newly-published work by Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin. It was an incredible year that Lutz characterizes, in his Introduction, as marked by the importance of surfaces, the standards by which everything is judged. And for every name or book the reader recognizes, there are ten (at least) that they will not. This is a feature, not a bug. I enjoyed the shorter entries on The Hard-Boiled Virgin and The Law of Success as much as the long entry on The Great Gatsby. It’s the kind of book you don’t think you have been missing until you open it.

The physical book itself is a thing of beauty and engineered to provoke a certain kind of reading that compliments the collection. After the Introduction, the entries simply begin and continue until the last page. There is no thematic index or lists of entries on similar topics. There are no strings of “SEE ALSOs” after the entries, nor are there photographs, images, or tables of relevant data. All of this to the good because the effect is that the reader is dropped like a mouse into a maze in which the cheese is everywhere. After the Introduction, the book has no true beginning or ending; it’s like a Möbius strip of literary history. Robert Frost said he knew “how way leads on to way” and that’s exactly the experience of reading 1925: there are times when one entry leads to an obvious follow-up, but many times in which one finishes an entry and then is struck by the incongruity of the next one, which then demands a reading. For example, here are all the entries from pp. 286-307:

Film

Ronald Firbank, Vainglory

Morris Fishbein, Medical Follies

Rudolph Fisher, “City of Refuge”

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Zelda Fitzgerald, “Our Own Movie Queen”

Julia A. Flisch, Old Hurricane

Silas X. Floyd, National Capital Etiquette

Norman Foerester, American Poetry and Prose

Football

Ford Madox Ford, No More Prairies

Henry Ford, The Dearborn Independent

Louis Forgione, Reamer Lou

Of course, you’re familiar with both Fitzgeralds and Fords as well as film and football—but the entries on people of whom you’ve never heard are as interesting as the ones on the superstars. Ronald Firbank was a Brit whose 1915 novel Vainglory was republished in the States; Medical Follies is a collection of Fishbein’s “snide” articles from The American Mercury; “City of Refuge” is a short story about an on-the-run African American’s first encounter with Harlem; Old Hurricane is an example of a genre now forgotten, the Southern “epic of the soil”; National Capital Etiquette was “written by a Black man for Black people” who wanted to learn how to dress and become popular; Foerster was instrumental in getting American Literature the street cred it needed to become the subject of PhD dissertations; The Dearborn Independent was a vehicle for Henry Ford’s anti-semitic vitriol; and Reamer Lou is a novel about the Italian immigrant experience. When I first received 1925 and knew I would be interviewing Tom, I thought that I would be a Very Good Host and read it straight through, cover-to-cover. But I found that this was difficult and then impossible, human attention being what it is; I ultimately decided that jumping around is how Tom would want it to be read, which is why it’s the kind of book you leave out so that you can read entries on Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Wallace Stevens, or Endocrinology when the urge comes upon you.

Stylistically, 1925 is unlike what one might expect, since Lutz often steps out from behind the expected curtain of encyclopedic prose to insert commentary about the subjects at hand. Wikipedia editors do a pretty good job of weeding out authorial subjectivity and those at World Book do even better. Lutz goes the other way, interjecting his opinions: in the entry on Medical Follies in the list above, Lutz explains that Fishbein wrote to defend the scientific method and expose fakery, adding, “A hundred years later, as we have seen quack cures for Covid touted by the White House and an anti-vaccine third party candidate for president appointed as Secretary of Health and Human Services, Fishbein’s critique remains relevant.” The one on Ford’s Independent ends with, “One hundred years later, automobile manufacturing innovator Elon Musk has been busy supporting the far right in Germany, giving Nazi salutes, and joining the fight against nonwhite immigrants. Plus ça change …” If these kinds of quick editorials bother a reader, he may want a more traditional encyclopedia, but the tradeoff would be losing Lutz’s voice and panache. When he mentioned to me that he was an admirer of David Thomson’s New Biographical Dictionary of Film, I told him that I was, too, and that I enjoyed 1925 for the same reason I enjoy Thomson’s Dictionary: in each work, the author’s opinions are on full display, not implied, and the reader engages with the writing much more than if he were reading anodyne, AI-generated fluff, regardless of whether he agrees with the author’s assessment of George Stevens or Wallace Stevens. Of Hemingway, for example, Lutz writes that he “was a terrible human being, as far as I can tell” and offers (for the sake of examining the greatness of 1925’s In Our Time) a passage from 1952’s The Old Man and the Sea which he precedes with, “I apologize if you have fond memories” of the book “from high school” and dismisses with the verdict, “Good grief.” The opening of his entry on Eliot’s Collected Poems begins: “As I grow older, I find that T. S. Eliot’s poetry continues to astonish me, but his criticism gets harder and harder for me to take seriously—he is self-righteous, precious, and annoyingly elitist.” If you find Lutz’s snark out-of-place, you’ve opened the wrong encyclopedia.

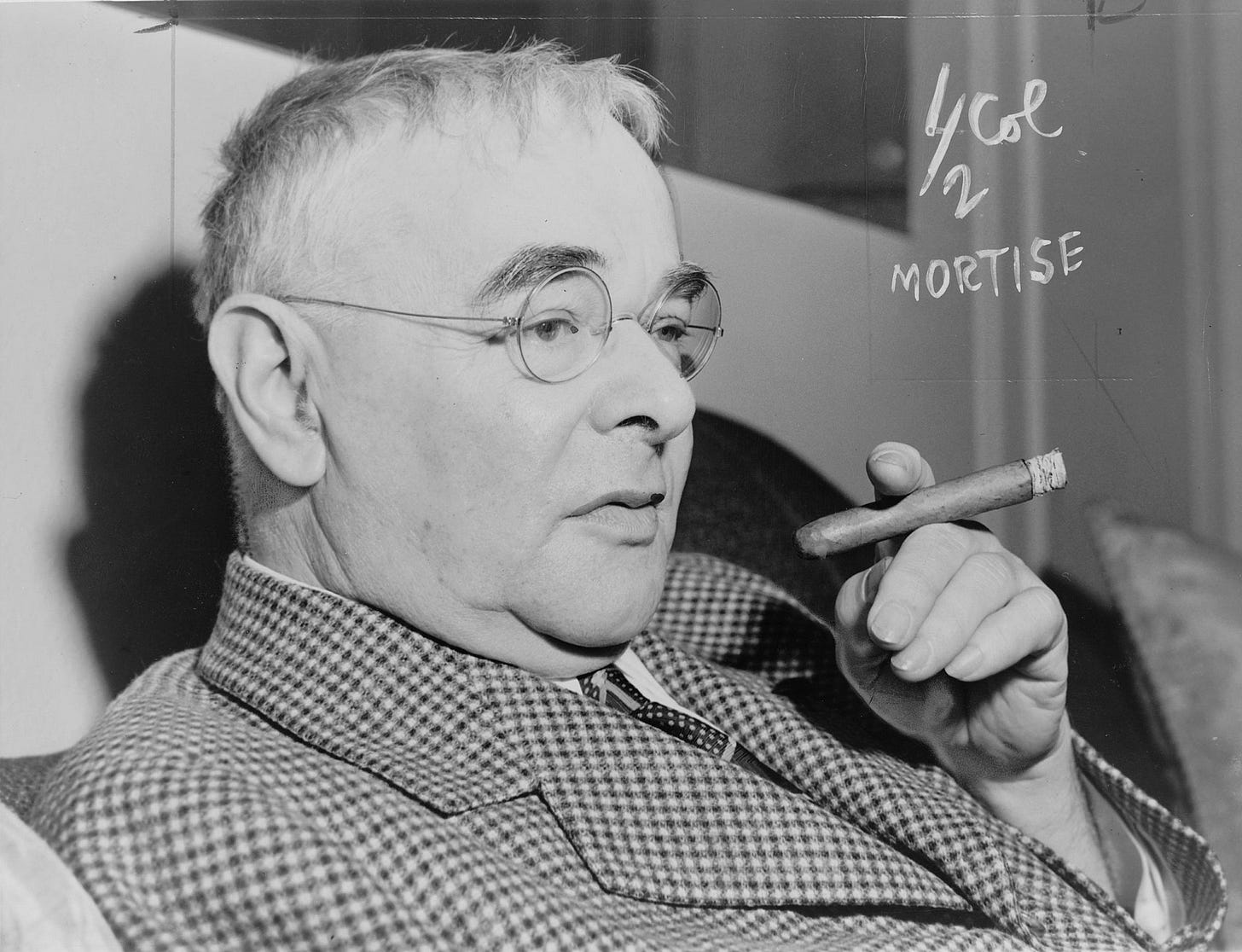

In light of Lutz’s politics and professorial pedigree, a reader may be surprised to learn of his opinion of H. L. Mencken, “a guy you cannot bring up in polite company” and a figure once central to American letters and culture but who is now persona non grata, if graduate students in English even recognize his name at all. Lutz tells a story in his Introduction about a time when he quoted the Sage of Baltimore to an academic colleague:

“I have a theory about that”—I no longer remembered what we were talking about— “because, as Mencken said, ‘a professor must have a theory as a dog must have fleas.’” She said, in a tone both dismissive and reproving, almost angry: “Well. I am not in the habit of quoting Mencken.”

But Lutz does quote Mencken in many entries and acknowledges that while he is “guilty as charged” of the many sins of -isms that the academy holds against him, he is smart, a great stylist, crucial to the growth of American letters, and interesting. Mencken’s American Mercury coverage of the Scopes trial was “a triumph of both belligerent journalism and cultural criticism,” his skill at “skewering” was unmatched, his “verbal pyrotechnics and omnidirectional insults” were “as anti-woke as one could be,” and his takedowns of academic critics read like Orwell with a dash of arsenic. And while Mencken may be dismissed as a racist today, Lutz points out that, under his editorship, American Mercury published more pieces by and about African Americans than all the other white magazines put together. “He was many things,” Lutz notes, and he discusses, rather than airbrushes, the laudable and lamentable in Mencken and the hundreds of other people described in the book.

Yet 1925 is not all Lutz shooting from the hip and offering his hot takes on everything: he takes great pains to have his subjects’ contemporaries do that. In the entry, “Book Reviewing in the 1920s,” Lutz states, “I have not, in my lifetime, seen the kind of vituperative, abusive, censorious responses to new books that were common to the book reviews of the 1920s anywhere except on Twitter.” He’s not exaggerating: 1925 is filled with quotations from original reviews that give the reader the sense of a culture that took print seriously. If someone was cancelled, it was less likely because of a bad life choice than bad writing. 1925 thus works as a time capsule and snapshot of literary values and assumptions.

The first entry I read was not on Fitzgerald, Eliot, or Hemingway, but on Joseph Hergesheimer. Like Keats’s name, literary reputations can seem like they were written on water and for years, Hergesheimer has been my go-to example when talking about the vagaries of public taste. His 1917 novel, Three Black Pennies, was the first American original published by Alfred A. Knopf. Samuel Beckett—no pushover—called Java Head (1919) one of the best novels he’d read. In 1922, a Literary Digest poll named him America’s most important writer, his books sold well, and he moved in the same circles as Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, and Mencken. Today he is invisible. The first thing Lutz says about him is, “Joseph Hergesheimer’s reputation has not held up”; he then quotes from his 1925 memoir From an Old House, in which the author affects a quasi-Jamesian delicacy that falls flat. This was the first passage of his I had ever read and, like the other ones skillfully chosen by Lutz to illuminate the entries, it reveals its author’s style, for good or for ill.

As if compiling the book were not enough, Lutz has also created a companion website on which readers of 1925 can find many of the texts in the encyclopedia. Be warned that the website is like the book: if you love the subject, you will spend a great deal of time clicking around just as readers of the book move from entry to entry. I read more of Hergesheimer’s memoir there, wanting to raise the old fellow from the dustbin, before I conceded to Tom Lutz’s judgement. Mencken said that criticism was prejudice made plausible, and 1925 could stand as Exhibit A.