Don't Lend Me Your Books

Unless You Don't Want Them Back

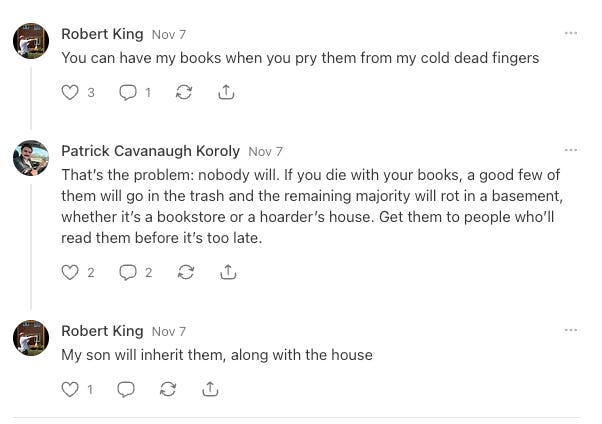

On November 6, 2025, Patrick Cavanaugh Koroly posted the following note:

If you have a collection of hundreds of books, it’s for the best that you learn to let other people borrow from it without obsessively fearing about getting them back. If it’s a particularly key book (a regular reference, one of special sentimental value), hold onto it, but what’s the point of all those stacks and shelves if they’re not being read?

He’s absolutely correct. Someone immediately objected or tried to wind him up; I couldn’t tell.

Again, point for Koroly. As Buzz and Woody know that toys are meant to be played with, books are meant to be read. If Pixar made Book Story, the protagonists would be a well-thumbed edition of Leaves of Grass, an uptight and condescending leather-bound edition of The Ambassadors, and a lovable yet untranslated Don Quixote. The plot would concern the struggle of a lonely and never-opened copy of Strategies of Maritime Insurance, 1772-1922 to finally find a reader. It would take some true Disney magic for that to happen, but anything is possible.

An unread book or one that’s been read once and then left to sit on a shelf is like an ignored toy: it’s supposed to bring joy but instead takes up space.

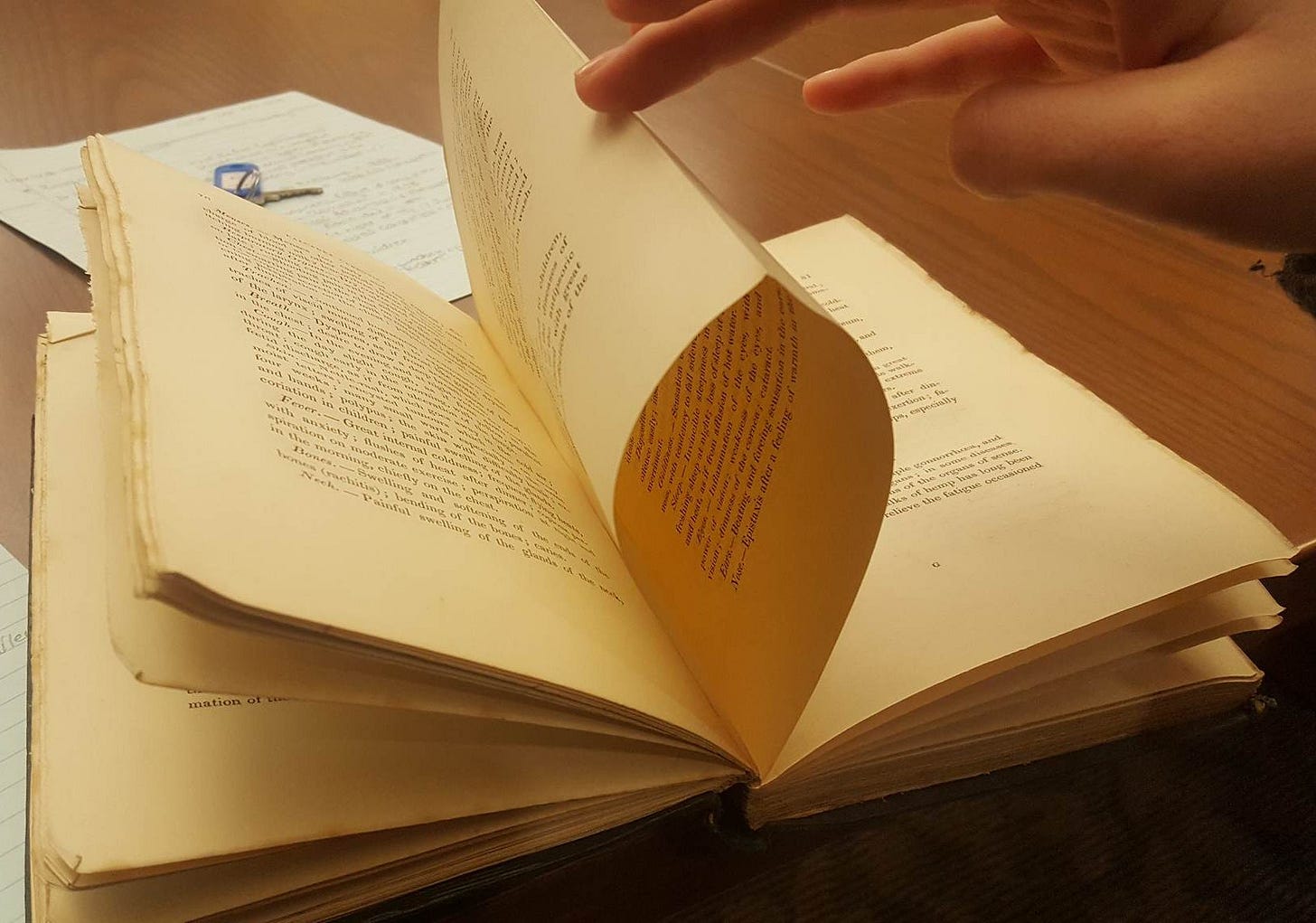

Some people amass books and display them like the heads of big game in a lodge. Substack abounds in photos in which people show off their home libraries, which impresses nobody except those who are impressed by the number of books a person owns. This is exactly the joke in The Great Gatsby when Nick wanders into Gatsby’s library and learns from Owl-Eyes that Gatsby is a “regular Belasco,” a nod to the famous theatrical producer. Gatsby has a set of The Stoddard Lectures, a series of talks given by the then-famous world traveler and photographer, to suggest their owner’s worldliness. The books are perfectly arranged, but the pages are uncut. There was a time when readers of hardcovers had to use a knife to cut the folded pages as they read—a look that remains today as an affectation in hardcovers and even some paperbacks. That Gatsby’s are uncut proves that the books were never meant to be read; they are meant to suggest something about their owner. I am Jay Gatsby, King of Readers; / Look on my books ye Substackers and despair!

The number of books a person owns or displays does not guarantee their skills as a reader. At the turn of the twentieth century, Harvard President Charles W. Eliot argued that a five-foot shelf would be long enough to hold the books that would engage a person for a lifetime. (The marketing of these titles as The Harvard Classics was targeted at Gatsbys everywhere, ready to display the handsome volumes in a prominent space. I’d bet many pages of volume 21, containing Mazoni’s The Betrothed, remained uncut.) What belongs on that five-foot shelf is another argument; the one here is that the actual number of books a person owns is not necessarily connected to their intelligence.1 Many home libraries are Potemkin villages of erudition. Owning books isn’t as important as reading them.

I’m not against owning books: I own too many and have written about the Japanese idea of tsundoku—the practice of hoarding never-to-be-read books. The argument here is that Patrick Koroly is right: if you enjoyed a book, be like Sting.

When I lend someone a book, I do so with the understanding that I will not get it back. The whole point of lending a book is to share one’s enthusiasm for it and the easiest way to kill any chance of that enthusiasm spreading is to add the element of pressure or social unease to the transaction. About twenty years ago, someone lent me five or six books when I said I wanted to learn more about the history of Scotland. I had casually mentioned this—I want to learn more about many things—and a week later, I was handed a stack of books. I was looking forward to reading them, so this wasn’t like when your cousin self-publishes a fantasy novel and gives it to everyone for Christmas. The first warning sign, however, was when the lender told me to “take care of them.” Did he think I was going to eat them? Use them as kindling? As a rule, I write all over my books: the idea that books can’t be “defaced” is as silly as the one about quantities of them on display. But I would never write in someone else’s or one from the library. Besides, these were plain paperbacks, not first editions of esoteric knowledge. Three weeks later, he asked if I had finished any of them. Sorry, no—not yet. I hadn’t even started. I had other irons in the fire at the moment. After another three weeks, I faced more questions and eventually just returned them without even a gracious white lie. “You obviously want them back,” I said, “so here. I don’t know when I’ll be able to read them.” The lender was shocked, I was irritated, and to this day I still don’t know much about the House of Stuart.

No less an all-star reader and lover of books than Samuel Johnson treated books roughly and never returned them. He had piles of them in his lodgings and was known to attack them with his hands as much as his mind. When his former pupil, the actor David Garrick, refused to lend Johnson his copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio, everyone who knew Johnson understood why: in his Life of Johnson, Boswell admits, “considering the slovenly and careless manner in which books were treated by Johnson, it could not be expected that scarce and valuable editions should have been lent to him.” Garrick was right in not lending the Folio; a fault would have been if he lent it and told Johnson that he had to wear white gloves, only have a pencil at hand as he read it, and finish it in two weeks’ time.

If a book is so precious that you hesitate lending it, keep it.

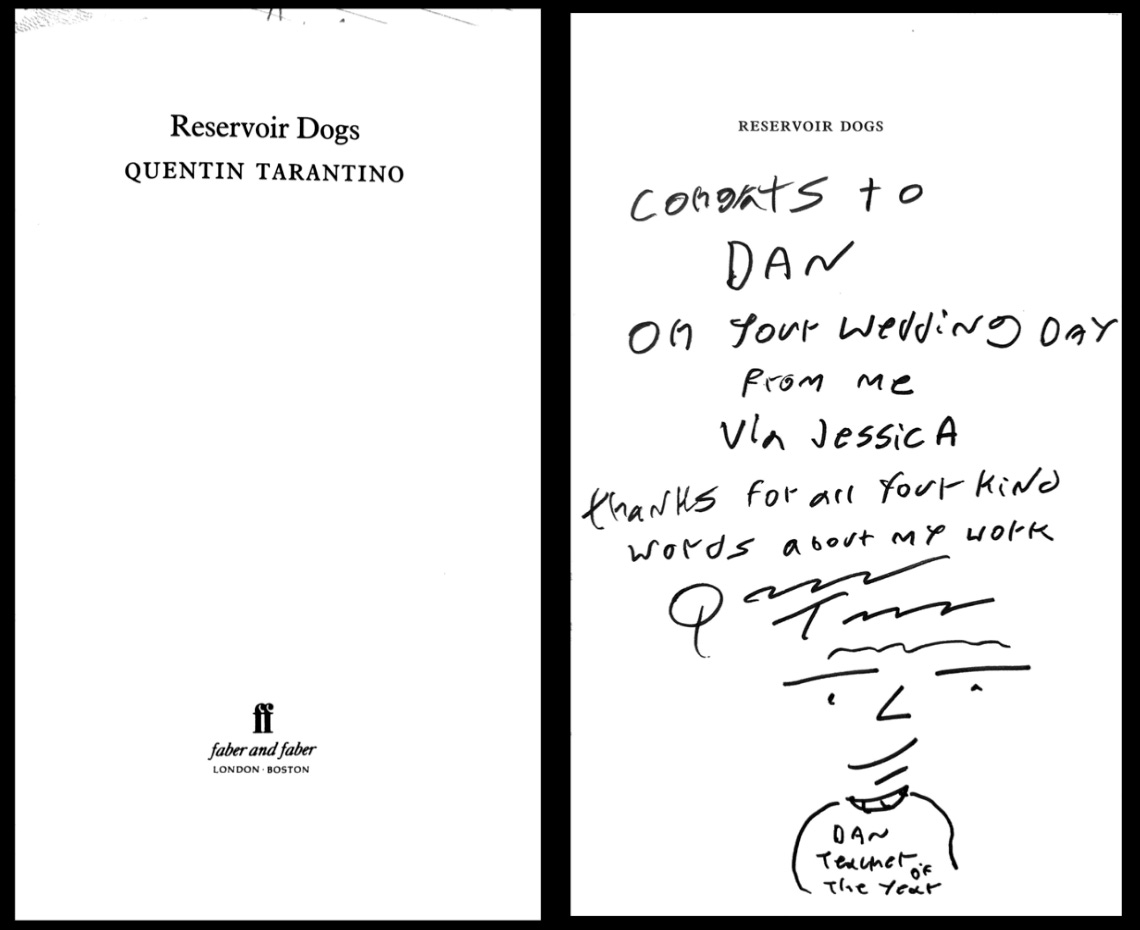

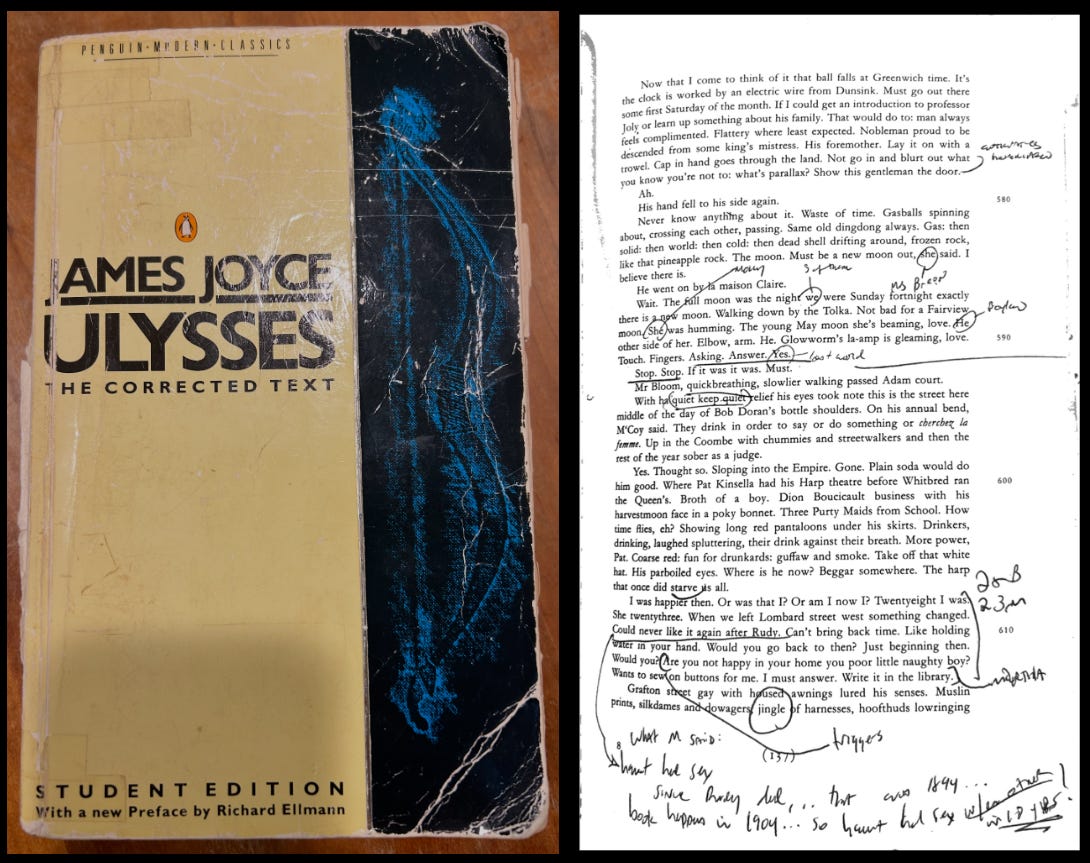

When I finish a book that I own, I give it away or donate it to the library. There are books I never lend not because they are valuable in the marketplace but because they are valuable to me. I have a signed edition of Charles Portis’s True Grit dedicated to me via a favorite professor, who made a pilgrimage to Arkansas to meet the great man. I have the Faber and Faber paperback screenplay of Reservoir Dogs dedicated to me by Quentin Tarantino, after two former students tracked him down and told him how much I enjoyed his films. And I have a number of books by Thomas Berger that he sent me when I told him how much I admired them. But there are also books that have even less obvious value: copies of books that I have annotated and taught. These have years of annotations scribbled in their margins and remind me, when I pick them up, what I thought about a passage or wanted to share with a class. I don’t want to lend my copy of Heart of Darkness because it’s a record of everything I’ve thought about that book since I first read it thirty years ago. And I won’t lend my battered edition of Ulysses I bought in Dublin and annotated like its obsessive author the first time I read it.

Besides, nobody wants them. If someone told me they wanted to read Ulysses, I’d urge a clean copy. If I become famous enough someday that readers want to comb my marginalia for insights into my thinking, they can have it.

I’m generally talking about books that we read once, enjoy, and then shelve, knowing we’re not going to read them again. And most of the books we read fall into that category: not everything demands annotation or multiple readings. When I read Agatha Christie’s A Pocketful of Rye last month, it was exactly what I wanted. I finished it over a weekend and gave it to my mother-in-law. I barely remember the solution; why do I need it cluttering my house? Thinking about this subject has made me wonder if there’s a protocol or flowchart that could be used when deciding if a book should be lent: if it’s covered in notes, you know you’ll reread it someday, or it has some sentimental weight, keep it. Otherwise, help someone else have a great experience in its pages.

When asked why The Grateful Dead allowed taping at their shows, Jerry Garcia said, “When we’re done with it, you can have it.”

Or, for that matter, their goodness. Substackers like to post photos of books they are reading next to a cups of coffee or glasses of whisky with captions like, “A piece of heaven” or “Me and Faulkner.” Reading will not make you a better person. There are many good people who never crack open a book and many voracious readers who are despised by their children. I can’t imagine not reading and it’s one of the fundamental ways to ensure a rich and interesting life, but it doesn’t make me a better person.

I’m torn on this, but you’re essay resonates. I do love my chronological (by date READ!) bookshelves (many boxes of unread). But also I can’t imagine I’d re-read more than 50 of them, which means I won’t ever re-read more than 20.

"Did he think I was going to eat them? Use them as kindling?" This made me laugh- great article!