It’s that time of year in which millions of Americans get ready to dress up and pretend, just for a day, that they are someone else.

This isn’t a late post leftover from Halloween. It’s about Super Bowl Sunday and people who make believe that they care about football.

I’m old enough to admit something I never would have said aloud as a kid: the excitement of football is completely lost on me. I find the pace excruciating and a full game like a Samuel Beckett play in which the audience experiences raw time. There’s as much action in a game as there is actual Batman time in a Christopher Nolan movie1—but this is an imperfect simile, since those movies are exciting. The arcane rules concerning penalties make the IRS tax code seem like IKEA instructions and are invoked every time something is about to happen. There are time-outs within time-outs, delays, restarts, and a bending of time that Einstein couldn’t explain. In soccer, hockey, and basketball, players are at least in constant motion, except for the last five minutes of any close NBA game. Baseball may seem slow, and there have been attempts by MLB to increase the pace, but there’s at least a rhythm to a game that is broken when something exciting happens—just like in soccer. (And daily life.) Even golf is one person against gravity, the ultimate foe working not only against the ball, but the muscles that set that ball in flight.

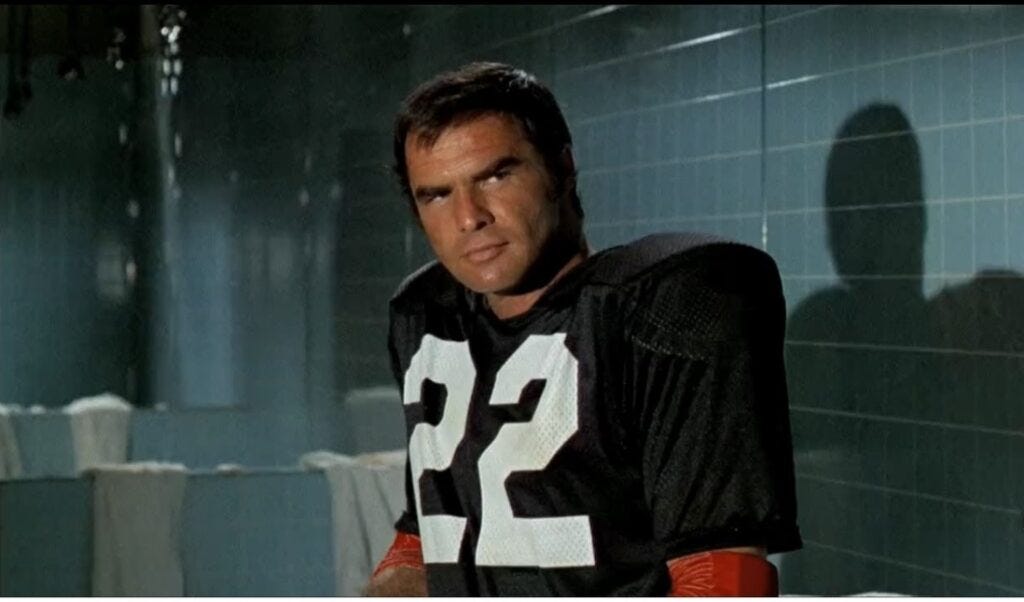

Perhaps this is why great pages and frames devoted to football are so rare. There are many good (and some great) films that involve baseball, boxing, basketball, tennis, hockey—even rugby. (I’ll leave Over the Top off of any list; we are still waiting for the Great American Arm Wrestling Film.) The best movie that involves football at all is The Longest Yard (1974), which isn’t a football movie as much as an excuse to have mid-70s Burt Reynolds walking around, breaking rules, and looking cool. Publishing is a similar desert for football-based fiction: in his Cinema Speculation, Quentin Tarantino calls Dan Jenkins’ Semi-Tough the funniest book ever written. It is not. It’s barely readable.

My complaints here are those of a crank, but—and this a key difference between me and other cranks—not one who wants his neighbors to turn down their music and bangs on the ceiling with the end of a broomstick. There are many fine folks who fully enjoy the gridiron and watch every game leading up to the big one. As the old cringeworthy line goes, some of my best friends are football fans. They listen to sports radio, read the coverage, and can speak the language of the game to each other like code talkers, filling conversations with miffs, coffin corners, play actions, and squib kicks. Their official jerseys show signs of honorable wear; they use the names of cities, not teams; they don’t need the instruction manual for Madden. They play fantasy football and win because they know what they’re doing. These are the true believers who deserve this day. They have paid for it with the currency of seventeen weekends, all leading up to the Sunday which they will spend watching hours of pre-game coverage before the coin toss. (They will also watch the short documentaries about the coin itself.)

My irritation is reserved for the fake fans, the ones who pretend to have a dog in the fight and who yell and scream over bowls of nachos without having any idea why they are yelling and screaming: those affecting an emotional stake in something about which they know almost nothing and truly care about even less. They pretend to have opinions on the outcome, but their opinions are always just short of any real specificity: “Well, you know, Philadelphia really has to move the ball if they want to break through that KC defense.” “The passing game is going to be really important.” “Kansas City just might do it again—we’ll have to see if the Eagles show up.” Growing up in New Jersey, I used to use this kind of language when asked if I thought the Giants or the Jets were “going to do it this year,” but now I just shrug and say, “I don’t know.” These false fans, not of any team, but of the sport in general, are like middle-schoolers buying Dark Side of the Moon T-shirts at Target who, if they heard “The Great Gig in the Sky,” would call it “boring,” “weird,” or “mid.”

Why do they do it? Why don’t they simply say that they’re not interested or that they’ll watch the game but don’t really follow football? People are afraid to admit this. Why not just watch it and eat the appetizers without the fake yelling and throwing up of hands when cued to do so by others in the rec room? And if you don’t follow football, why watch it at all? The reason may have to do with the fear of smalltalk at work on Monday: having no answer when the first of many colleagues asks what you thought of the game is, to some, the equivalent of showing up to work without pants. Samuel Johnson said that no man is a hypocrite in his pleasures—in other words, people’s pleasures show their real selves—but there are people who care nothing for football and will still watch the Super Bowl without pleasure for the sake of avoiding embarrassment.

In his Dictionary of 1755, Johnson defines “affectation” as “an artificial shew; an elaborate appearance; a false pretence” and elsewhere calls it “the art of counterfeiting those qualities which we might, with innocence and safety, be known to want.” Those qualities are a deep knowledge of a game that they really don’t enjoy; if the only game you watch all year is the Super Bowl, you don’t really enjoy football. The affectation is understandable because we all want to be with the cool kids, who, more often than not, were athletes or the people who hung out with them. There’s a scene early in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in which ten-year-old Stephen plays soccer at school, yet “kept on the fringe of his line … feigning to run now and then.” He’s supposed to care about the game but just pretends to do so; he isn’t brave enough to tell how he’d rather spend his free time. (That comes later.) Johnson again: “He that, with an awkward dress, and unpleasing countenance, boasts of the conquests made by him among the ladies, and counts over the thousands which he might have possessed if he would have submitted to the yoke of matrimony, is chargeable only with affectation.” The awkward dress of a crisp, new Travis Kelce jersey, purchased at Dick’s on Saturday, February 8, is a costume worn for the same reason a kid wears one of Iron Man: it’s a chance to pretend one has a kind of clout that eludes one the rest of the year.

Everyone may be entitled to an opinion, but opinions are matters of knowledge. Meaningful fandom can only be earned over a long stretch of time and it can’t—shouldn’t—be faked.

The Catcher in the Rye begins with the ostracized Holden Caulfield on a hill overlooking the prep-school equivalent of the Super Bowl. “The game with Saxon Hall was supposed to be a very big deal around Pencey,” he says. “It was the last game of the year, and you were supposed to commit suicide or something if old Pencey didn't win.” Holden dislikes phonies of every sort, including those who pretend to have emotions about sports about which they don’t really care. But he may be a little too harsh. If he knew there were people who say they only watch the Super Bowl for the commercials, he’d throw up his hands and say, “I don’t even want to talk about that.”

The percentage of screen time in which Bruce Wayne is actually Batman: Batman Begins: 17%; The Dark Knight: 18%; The Dark Knight Rises: 13%.

A good thing about the incredibly destructive rise of sports gambling is that it’s easier for fake fans to have material rooting interests in not only the game’s outcome but also who wins the coin toss.

[Rushes to dig out DVD of Horse Feathers] Don’t forget the olympics, like anyone cares about gymnastics the other three years.

I would make a similar argument about how people get breathless over the economy, when even economists are usually grasping at straws, or everyone goes wild for mardi gras with zero intention of giving up anything for lent. Humans gonna human, I guess.