Everybody loves Robert Rossen’s The Hustler (1961), and with good cause. Paul Newman is so young (36 but passing for 26), so cocky, and so much fun to watch as Fast Eddie Felson that we tell ourselves that we need to rewatch more of his movies immediately. But the supporting actors are also first-rate: Piper Laurie as Sarah, the lonely alcoholic; Myron McCormick as Charlie, Eddie’s initial manager and George C. Scott as Bert, his second; Murray Hamilton (who should have had his name legally changed to “The Mayor from Jaws”) as the dandy who challenges Eddie to “billiards”; and, of course, Jackie Gleason as Minnesota Fats. Knowing that Gleason did all of his own pool shots adds a level of enjoyment like we feel when we watch Mission Impossible and know that Tom Cruise is really hanging out of a plane or jumping off of a motorcycle. When Morley Safer, for a 60 Minutes piece, asked Jackie Gleason why Orson Welles dubbed him “The Great One,” Gleason replied, “You’ve seen me shoot pool, haven’t you?” Add the smoke, long silences, gorgeous photography and a thirty-six minute opening scene that’s so intense that when it’s over the viewer exhales and realizes There’s a whole movie after this! and you have a perfect film.

It’s also a perfect book. My copy is a classic movie tie-in; like so many of the paperbacks from that era, it’s undersized (6” x 4”) and the edges of its pages are, like its cover, the color of money. It’s designed to fit in a drug-store rack or back pocket and announces its pulp pedigree with its price (35¢) and description (“drifters, sharks, and lushes”). But there’s also a nod to respectability in a New York Times blurb, hailing it as a “fine, swift, wanton, offbeat novel,” with “wanton” the clear reason for why this blurb was chosen. And that’s exactly what makes The Huster terrific: it combines a noir plot in a “strange smoke-filled world” that makes readers turn its pages with a serious examination of the use and abuse of talent. It aims low and high and hits both targets. It does the work of a dime-store thriller and of genuine art: it holds us in its grasp as it holds the mirror up to nature.

The original 1959 cover makes the novel seem more playful or light than it is: its description (“In the big game Fast Eddie was risking his life”) promises suspense, although readers find that Eddie never, literally, plays for his physical life.

Instead, he plays for his psychological one. Tevis gets at the heart of why people like Eddie Felson–people with incredible talent with which they were born–wrestle with how to channel it. The book explains why rock stars burn out, why celebrities embarrass themselves, and what happens when athletes become too famous too quickly. It also refutes, long before it was popularized by Malcolm Gladwell (and, to be fair to him, misunderstood) the too-often-cited “ten thousand hours rule.” (If I seriously practiced pool for ten thousand hours, I still couldn’t beat Fast Eddie or hold my own with Minnesota Fats. Neither could you.) Talent is a gift, and the essence of every gift is that it is unearned: you can’t buy it literally with lessons or figuratively with a punch-clock. You have it and don't know why you were chosen to receive it. But you do know that you want to use it because you find it leads to something exciting and meaningful. In a scene in the film in which Eddie and Sarah go on a picnic while he is nursing his broken thumbs, Eddie tries to articulate (with phrases from different parts of the novel) these vague yet powerful ideas:

You know, like anything can be great, anything can be great. I don’t care, bricklaying can be great, if a guy knows. If he knows what he’s doing and why and if he can make it come off. When I’m going, I mean, when I’m really going, I feel like a ... like a jockey must feel. He’s sitting on his horse, he’s got all that speed and that power underneath him ... He’s coming into the stretch, the pressure’s on him, and he knows ... just feels... when to let it go and how much. Cause he’s got everything working for him: timing, touch. It’s a great feeling, boy, it’s a real great feeling when you're right and you know you’re right. It’s like all of a sudden I got oil in my arm. The pool cue’s part of me. You know, it’s a pool cue, it’s got nerves in it. It’s a piece of wood, it’s got nerves in it. Feel the roll of those balls, you don't have to look, you just know. You make shots that nobody’s ever made before. I can play that game the way nobody’s ever played it before.

“There was a kind of power,” Tevis says about Eddie’s gift, “a kind of brilliant coordination of mind and skill, that could give him as much pleasure, and as much delight in himself and in the things that he did, as anything else in the world. Some men never felt this way about anything; but Eddie had felt it, as long as he could remember, about pool.”1 Some men never felt this way about anything–a line so true that Rossen has Sarah speak it after Eddie’s monologue and a reminder that we live in a world that urges us to keep infinitely scrolling and stay comfortably mediocre and stupid. No wonder Eddie wants to feel “this way” as often as he can.

This feeling of being “in the zone,” where one’s distractions and anxieties and even self-awareness fade, is what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1934-2021) called the state of “flow,” a form of “optimal experience” (3) that consumes a person and, after it ends, motivates the person to seek it again. Flow is temporary; were it not, we would be unable to do anything else in our normal lives. The guitarist playing a solo, the striker advancing up the pitch, and the bricklayer mentioned by Eddie all work toward something: musical rapture, athletic exhilaration, mastery of a craft–and this working-towards is where flow is found. When Csikszentmihalyi studied people from an array of endeavors who experienced the flow state, he found them motivated by “the quality of experience they felt when they were involved with the activity.” And this experience was not the kind of experience sold to us by the usual suspects:

This feeling didn’t come when they were relaxing, when they were taking drugs or alcohol, or when they were consuming the expensive privileges of wealth. Rather, it often involved painful, risky, difficult activities that stretched the person's capacity and involved an element of novelty and discovery.2

To truly enjoy an experience to the point where one reaches the state of flow, different elements need to be present–and all of these are potentially present when Eddie shoots pool. The activity needs to require skills, be goal-directed, offer clear feedback as it happens, foster intense concentration, allow for an exercising of control over one’s situation, and suspend self-consciousness (49-63). When these elements are in play, a person has a greater opportunity to achieve the state of “optimal experience” chased by artists, athletes, and amateurs. Eddie can hustle in smaller poolrooms all his life, but he wants something more satisfying than taking traveling salesmen for $20 a game: he wants Fats the way that Ahab wants the white whale, for to defeat him will be both meaningful and thrilling. Everything else is small fish.

Fats’s table at Bennington’s is where flow is to be found. His enormous body matches his reputation and talent–and Tevis wants the reader to know that while Fats may be heavy, he’s no slob: his hair is perfectly combed, his nails are manicured and polished, and he moves around the table as if he were in a ballet, “the steps light, sure, and rehearsed” (42). (As Paul Newman watches Jackie Gleason play, he whispers, “He’s like a dancer!”). He cuts a formidable figure, never engaging in banter, even when baited: when Eddie tells him, “I’m the best, no matter who wins,” Fats responds, “We’ll see” (52). He is the perfect test of Eddie’s talent: when Charlie expresses his reservations about Eddie challenging the best, saying, “For Chrissake, I don't yet know how good you are,” Eddie responds, “Well, I don’t, either, Charlie” (33). Only by facing Fats on his home ground can Eddie find out and–if he’s good rough–experience a state of flow reserved only for those who work at the height of an endeavor. Rocky Balboa doesn’t want to fight Apollo Creed for the purse, but for the sense of purpose. Eddie doesn’t want the cash as much as he wants to enter the flow state, even if he can only articulate the value of that state with a stack of folding money. (Eddie isn’t a substack writer or psychologist, but a hustler.)

As his first marathon with Fats gets underway, Eddie begins to detect the presence of something like a new aspect of experience: he “began to feel the sense he sometimes had of being a part of the table and of the balls and of the cue stick.” As “the stroke of his arm seemed to move on oiled ball bearings” (43), Eddie is moving toward a state in which he will, in Csikszentmihalyi’s terms, “break through what the body can accomplish” (96). Fats raising the stakes to a thousand a game is exactly what Eddie needs to push him into this new state: the stakes are financial, but also experiential. His senses become heightened to the point where “the balls had sharp, jeweled edges” (44) and he knows that he cannot miss: “Nothing could be so clear or so simple or so excellent to do” (44). As he continues to beat Fats, despite the champion’s “brilliant” and “fantastically good” (44) playing, Eddie reaches a kind of nirvana in which what’s happening on the table mirrors what’s happening in his “soul”:

Eddie beat him, steadily, making shots that no one had ever made before, knifing balls in, playing hairline position, running rack after rack of balls without his cue ball’s touching a cushion, firing ball after ball into the center, the heart of every pocket. His stroking arm was like a conscious thing, and the cue stick was a living extension of it. There were nerves in the wood if it, and he could feel the tapping of the leather tip with the nerves, could feel the balls roll, and the exquisite sound they made as they hit the bottoms of the pockets was a sound both there, on the table, and in the very center of his own soul (46).

Nabokovian in its depiction of rapture and the key to Tevis’s novel, this passage epitomizes the feeling of flow that Eddie wants even more than money: the money simply allows him to chase the feeling. It’s the cost of admission to the place where he can feel what Csikszentmihalyi calls “total involvement with life” (xi) because the experience is more “rich, intense, and meaningful” (70) than that found anywhere else. (Or with anyone: Eddie has much more of an emotional tie to Fats than he does to Sarah, his love-interest.) Without money, Eddie would have to take a day job and abandon his search for the next time he can achieve the flow state. Terry Malloy wanted to take down Wilson at the Garden not for the money, but because he could have been a contender, someone who knows the feeling of being the best at what one does; Eddie taking down Fats is Terry’s dream realized in a different arena.

The marathon session against Fats continues for two days, illustrating another element of the flow state: the bending of time. When one is fully absorbed in an activity through intense concentration, time may move quickly or slowly, but never at the same rate as the clock: what Csikszentmihalyi calls “freedom from the tyranny of time” (67) adds to the exhilaration. But this freedom cannot be sustained and Eddie’s attempt to extend it past its expiration reveals his desperation and immaturity. After Fats begins winning on the second day, Eddie demands that Charlie give him his winnings. When Charlie refuses, Eddie calls him “chicken” and blows through nearly twenty-thousand dollars in an effort to recapture the experience. When Fats ends the game after forty hours because Eddie has blown the bank, Eddie collapses and begins vomiting, his physical self reflecting the emotional blow of not being able to get back to the state of flow. Talent alone is not enough; people often need some form of gatekeeper, whether it’s another person or a set of pretty strong internal guardrails. As Bert, Eddie’s second manager later tells him, “I’m hard with myself and I know when not to go weak” (154). The taste of flow is like that of other powerful intoxicants. This is why The Hustler is a great portrait of talent without restraint or wisdom (see also Belushi, John; Gooden, Dwight; Morrison, Jim; et al). Eddie is accused of being unable to hold his liquor, but, as Bert says, Fats drank just as much. Eddie’s problem is that he can’t hold his talent.

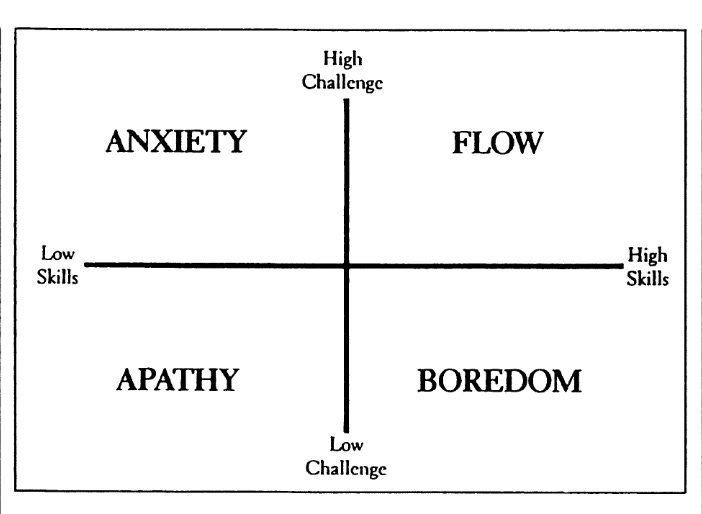

There are a number of ways to graphically represent Csikszentmihalyi’s ideas. Here’s one that’s especially clear:

Apply this to any endeavor you practice and you’ll see it makes sense. If you love to bake and rate yourself at a 4 out of 10, making Betty Crocker cupcakes will place you in the bottom-left, creating a wedding cake will shoot you to the upper-left, but a cherry pie may be what you need to get to that upper-right. As your skills increase, so will the level of your challenges and relation to the graph: that same baker, two years later, may be working as an 8 out of 10 and find that something more complex than cherry pie is needed to get into the flow quadrant. Hustling traveling salesmen on the way to Chicago keeps Eddie in the safe but boring bottom-right; he knows that playing straight pool against Fats will place him in the beautiful upper-right.

These quadrants are not separated by walls of iron. When Eddie is forced to play Findlay in billiards instead of pocket pool, he begins the game in the upper-left quadrant: he has the skills to shoot, but the challenges of doing so on a longer table with slightly heavier balls were “not easy for a pool player to get used to” (181) and Eddie cannot “get the feel of the game” (183) as Findlay continues to beat him. But once Eddie calls upon the reserve of “character” that Bert has been urging him to build for the whole novel, he moves across the y-axis into the upper-right and takes twelve thousand dollars. He doesn’t go too far into that quadrant–Findlay is no Fats and Eddie wins more out of anger than to reach a state of bliss–but he has learned how to get there by playing with patience and prudence: two elements of character he lacked when he insisted on showing up the hustler in Arthur’s and getting his thumbs broken for it. This is why the chapter ends with Eddie declaring, “I’m ready” (195).

Part II coming soon!

Tevis, Walter. The Hustler. Dell Publishing Company, 1959. p. 130. All subsequent quotations are from this edition.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. HaperCollins, 1990. p. 9. All subsequent quotations are from this edition.

![The Hustler - [FILMGRAB] The Hustler - [FILMGRAB]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KOT4!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4056a2f8-649f-4c37-a510-8f87e53a4309_1280x546.jpeg)

One of my three favorite Newman films and one of the best portrayals of alcoholism and it’s destruction of talent. Hope you cover Color Of Money at some point. Great read!

I've never seen this movie, and shame on me. I am very interested in the idea of flow and how you relate it to Gladwell's assertions here. This is shit I think about all the time. Thank you for this piece. Well written.