To his future biographer James Boswell, Samuel Johnson said regarding biography, “It is rarely well executed. Only those who live with a man can write about his life with any genuine accuracy and discrimination; and few people who have lived with a man know what to say about him. The chaplain of a late bishop, whom I was to assist in writing some memoirs of his Lordship, could scarcely tell me anything.”

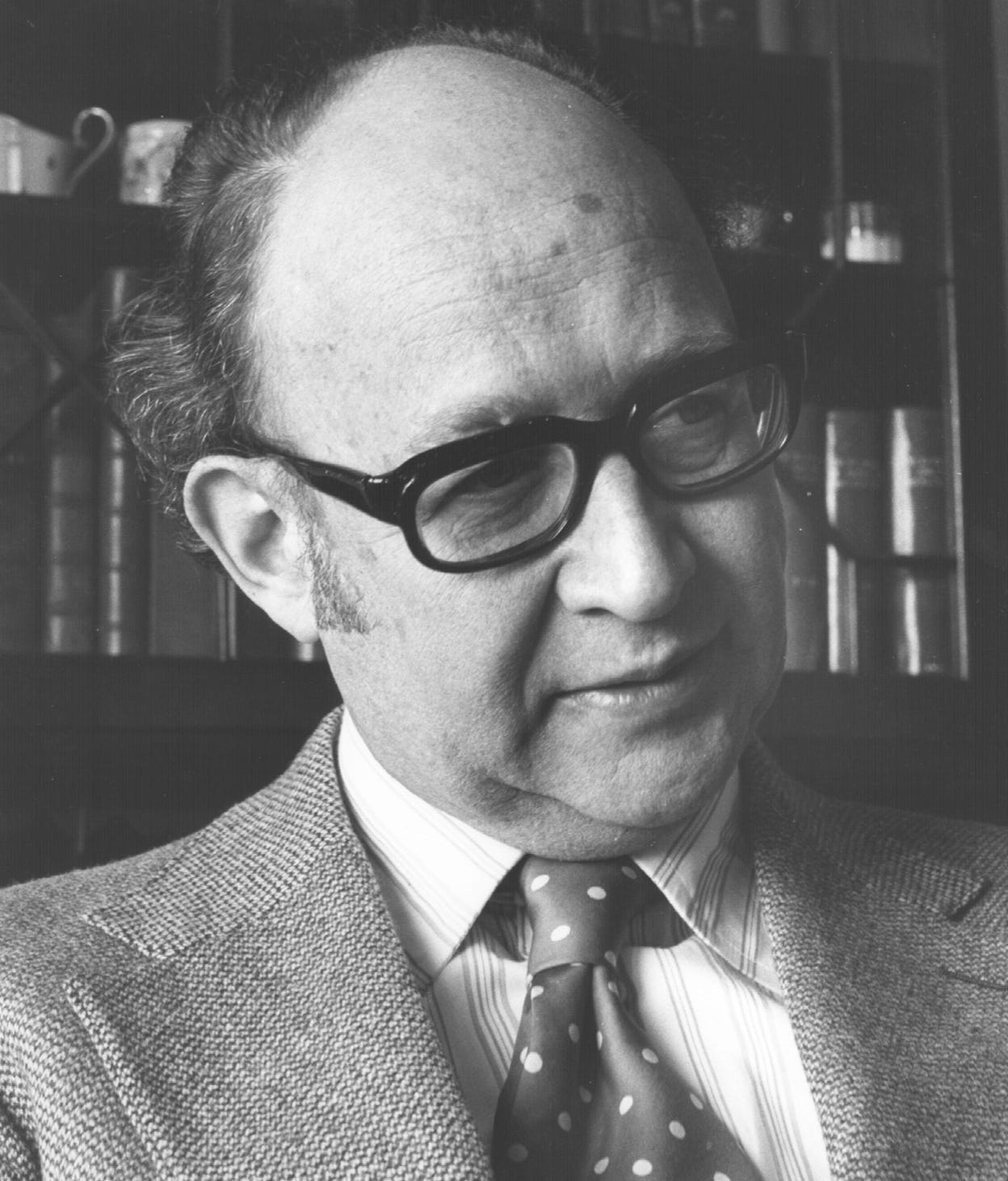

Richard Ellmann never met James Joyce in the literal sense but lived with him as a biographical subject for much of his life—and could tell you anything and everything about him. His cinderblock of a biography, first published in 1959 and revised and expanded in 1982, is as overwhelming in its level of detail as Ulysses is about Leopold Bloom. And as Joyce had great affection for his protagonist, Ellmann does for his. James Joyce is exhaustive and exhausting and there are moments when it becomes so inside baseball that the reader might look up and need to be reminded of why he or she began the book in the first place: the narrative might be focused on Joyce as creator of a new means of novelistic expression or then a new language with which to imitate the mind asleep and then move to Joyce as a renter of flats and eater of dinners. Joyce made clear to one of his potential biographers “that he was to be treated as a saint with an unusually protracted martyrdom”1 and Ellmann never argues for canonization. As Hamlet says of his beloved father, “He was a man, take him for all in all.” Ellmann does.

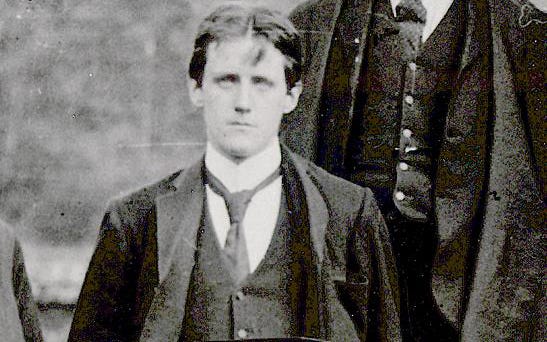

Readers of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man will find that Joyce didn’t change much as he transformed his life into art. Stephen Dedalus is a barely-reshaped version of his creator. The definite article in the novel’s title points more to the author rather than an archetype. His time at Clongowes, his “cruel and unjust and unfair” flogging at the hands of a sadistic prefect, the sermons about Hell, the sexual and artistic awakening, the deteriorating relationship with his father (and authority in general), and the decision to escape Ireland, “the old sow that eats her farrow,” are all there. “At the age of twenty-one,” Ellmann writes, “Joyce had found he could become an artist by writing about the process of becoming an artist, his life legitimizing his portrait by supplying the sitter, while the portrait vindicated the sitter by its evident admiration for him” (145). There was never any question about his artistic vocation or his assumption that he could only heed the call on the continent. Like the American high-school senior who forsakes the state university because he, like Coriolanus, thinks there is a world elsewhere, Joyce was convinced that only in flight could he pursue his talents. Late in Portrait, Stephen regards his last name as prophetic; Joyce told himself that he would find a career in medicine, but knew as he attended classes in Paris that he couldn’t dodge his real vocation to (as Stephen says) forge in the smithy of his soul the uncreated conscience of his race.

He never went home. Self-exile fit the image of himself he longed to cultivate and “whenever his relations with his native land were in danger of improving, he was to find a new incident to solidify his intransigence and reaffirm the rightness of his voluntary absence” (109). In a reversal of the classic break-up line, Joyce told Ireland it’s not me—it’s you. Yet being absent from Dublin sharpened his vision of it and he offered his work as universal: “I always write about Dublin,” he said, “because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world” (505).

Ulysses became the city’s beating heart and Ellmann takes readers through its composition, noting (in a perfect phrase) that it was the first novel to allowed readers to “enter the mind of a character without the chaperonage of the author” (358). Joyce regarded Ulysses as the ultimate character: a son, father, husband, lover, leader, inventor, philosopher, friend, warrior, tactician–a “complete man” (436). Leopold Bloom was also complete, not in all of these endeavors but in terms of what his creator revealed about him. Readers of Ulysses know that Bloom is not altogether different from the reader—situations and tragedies may differ, but just as one city could stand for all cities, one man could stand for all men. The completeness of Joyce’s approach lay not in placing his hero in a number of different situations, as Homer did, but in writing about one basic situation, 16 June 1904, in a number of different ways. “A writer,” Joyce remarked, “should never write about the extraordinary. That is for the journalist” (457). Homer uses one style to describe dozens of extraordinary situations; Joyce uses dozens of extraordinary styles to describe a single day. The Quaker librarian in Ulysses says, “Our national epic has yet to be written,” but he didn’t know he was a character in it.

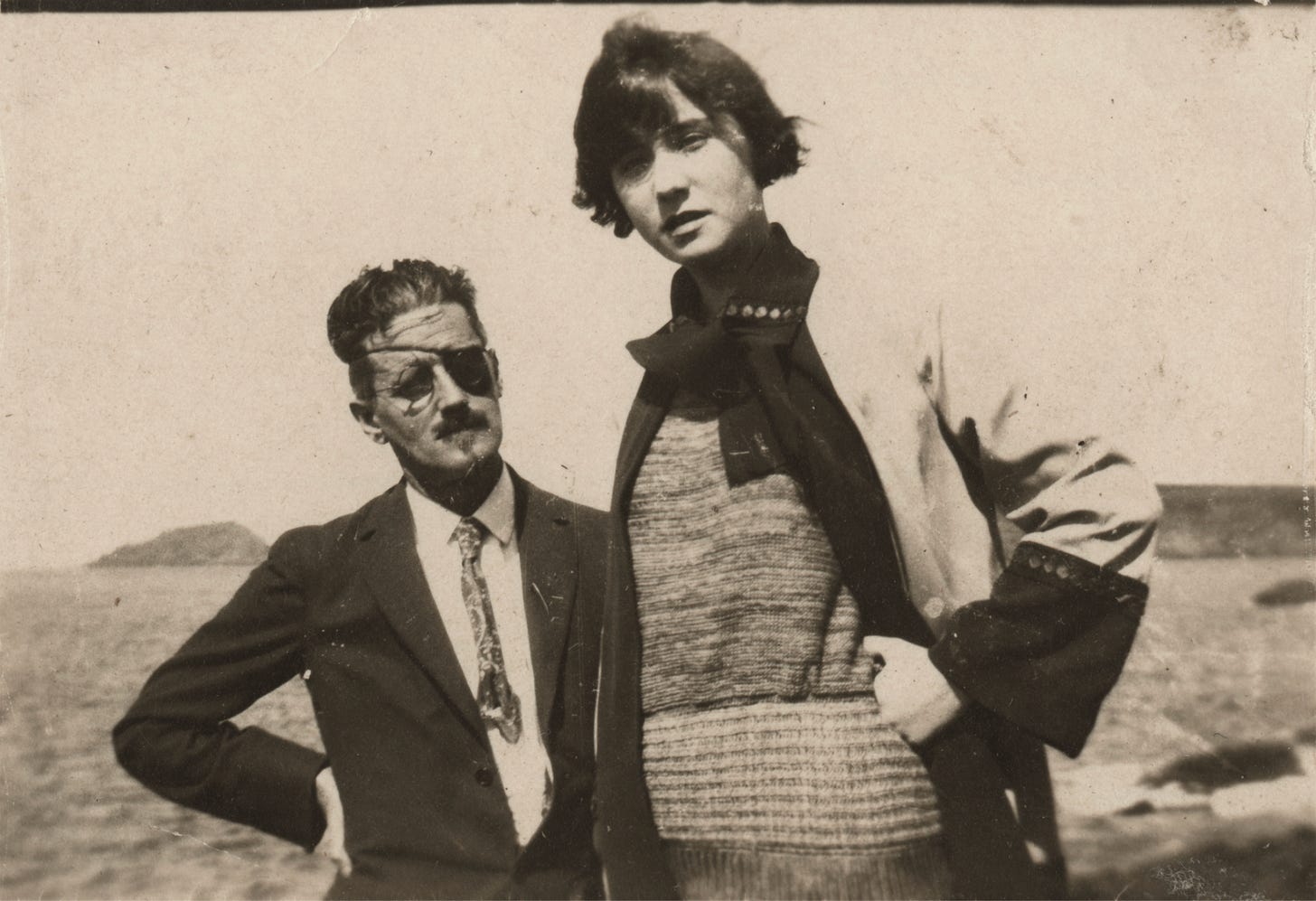

Nora Barnacle, who eventually married Joyce in 1931 to guarantee their children’s inheritance, stood by Joyce in every way except the one we’d take for granted: she read fewer of his pages than a reluctant undergraduate. When friends in Zurich called upon them in 1918, Joyce picked up a copy of Perl-Romane, the equivalent of People, and said, “This is what my wife reads” (434). At a party almost twenty years later, she told him, “Well, Jim, I haven’t read any of your books but I’ll have to some day because they must be good considering how well they sell” (722). He could have commiserated with Flannery O’Connor, whose mother never made it past the opening pages of Wise Blood and urged her daughter to write the next Gone with the Wind. This made O’Connor grind her teeth, but Joyce seemed to not mind Nora’s indifference. Anyone who has a Substack might find Joyce’s attitude heroic, since we tend to ask our friends and family if they’ve “had a chance” to read our latest post. Imagine if that post were Ulysses.

Ulysses was published in Paris on Joyce’s fortieth birthday in 1922. In 1924, fewer people read Finnegans Wake as pieces of it were circulated as Work in Progress; it was eventually published in 1939. That piecemeal reading still seems the case today, at least among people I know. Joyce called Ulysses his book of the day and Wake his book of the night; just as consciousness blurs images and events together as we sleep, Joyce wanted to make the language do the same. He meant it to be heard rather than read, but his contemporaries wouldn’t hear of it. H. G. Wells wrote him, “Who the hell is this Joyce who demands so many waking hours of the few thousands I have still to live for a proper appreciation of his quirks and fancies and flashes of rendering?” (608) Ezra Pound (a great champion of Joyce) wrote him:

I will have another go at it, but up to present I make nothing of it whatever. Nothing so far as I can make out, nothing short of divine vision or a new cure for the clapp [sic] can possibly be worth all the circumambient peripherization.

Doubtless there are patient souls, who will wade through anything for the same of the possible joke. (584)

Richard Ellmann is one of those patient souls who has internalized the Wake to the point that he uses passages as epigraphs for almost every chapter and quotes it extensively in the footnotes to show how Joyce incorporated events from his life into his last work. He assumes his reader shares his enthusiasm for Joyce’s dream-language and, in small doses, it works: in the chapter that treats Joyce from ages 18-20, he offers the epigraph, “He even ran away with himself and became a farsoonerite, saying he would far sooner muddle through the hash of lentils in Europe than meddle with Ireland’s split little pea.” Joyce and Stephen were certainly farsoonerites. And while I’ll probably never attempt to read Finnegans Wake and side with Wells and Pound, Ellmann is great at portraying its author as someone searching for a new way to depict the fluidity of dreams and history.

Joyce ended his life worrying about his daughter, Lucia, as much as the Wake. A schizophrenic who sometimes became violent and had once developed an infatuation with Samuel Beckett, Lucia moved from institution to institution and under the care of numerous doctors, including Jung, each of whom told Joyce what he refused to hear. Ellmann presents Joyce as “foolish fond like Lear” (686) in his assumption that his daughter could be cured if she could only find the right treatment. When describing one of Joyce’s lowest points regarding her, Ellmann writes, “His exasperation and despair exfoliated like a black flower” (684). He doesn’t often offer comparisons like this, but when he does, he perfectly hits the mark. Lucia died in 1982.

There is less drama in Joyce’s life than in that of Ellmann’s other great biographical subjects, Yeats and Wilde. But there is certainly plenty. Joyce was a self-promoter and Ellmann details a fascinating episode in which he opened the Cinematograph Volta, the first cinema in Dublin, which opened in 1909 and closed ten years later. One of the most recognizable human failings, common to all men in all places, is Joyce’s worrying a great deal about money yet never scaling back his spending. As a twenty-something in Trieste, “He did not believe in the poverty in which he dwelt” (254) and as he grew older, he would splurge on dinners and gifts for Nora while not knowing how the rent would be paid. Yet there was always someone ready to help him, most notably his benefactress (and eventual literary executor) Harriet Shaw Weaver. When Mr. Deasy, early in Ulysses, tells Stephen Dedalus that the proudest boast an Englishman can make is I paid my way and asks Stephen if he can do the same, the artist-become-schoolteacher thinks of his portfolio:

Mulligan, nine pounds, three pairs of socks, one pair brogues, ties. Curran, ten guineas. McCann, one guinea. Fred Ryan, two shillings. Temple, two lunches. Russell, one guinea, Cousins, ten shillings, Bob Reynolds, half a guinea, Koehler, three guineas, Mrs MacKernan, five weeks’ board. The lump I have is useless.

He answers, “For the moment, no.” Joyce only began to pay his way once sales of his books began to rise, along with his reputation.

And that reputation is inseparable from the human failings and triumphs of the man of flesh and blood. Joyce knew about the rumors and false ideas spread about him, noting in a 1921 letter that some assume he is “extremely lazy,” others that he is an “incurable dipsomaniac,” and others that he is literally mad and should be committed to a sanatorium. “I mention all these views not to speak about myself but to show you how conflicting they all are. The truth probably is that I am a quite commonplace person undeserving of so much imaginative painting” (510). In his wonderful obituary of Ellmann for the British Academy, Nicolas Barker writes:

Ellmann knew the value of facts; establishing the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth was to him a sacred duty. He also knew that there was a further kind of truth, unsupported by facts, the legend that grows up round the great that can never be wholly detached from reality. It was not right to treat it as just a failure in the record, a defect for which allowance had to be made, but rather as part of a greater reality, no less real because less true.

The legends arise because most of us can’t imagine the people who create great art as being “quite commonplace.” There has to be a catch, a glitch, that helps explain things. How does a “commonplace person” write The Divine Comedy or Hamlet or Ulysses? Ellmann’s achievement is revealing the literal truth while never assuming that the legendary one is beneath his consideration. The art draws us to the legends and the legends draws us to the biographies. Ellmann satisfies every kind of investigation into every version of his subject.

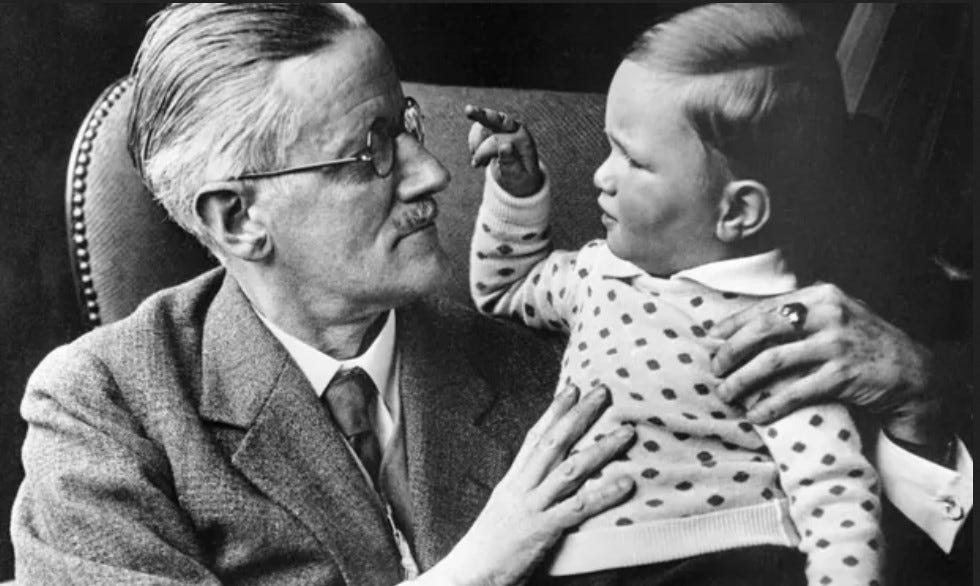

Joyce died in 1941, Ellmann in 1987. We are lucky to be living with them still.

Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (Oxford University Press, 1982), 631. All subsequent page numbers are from this source.

I remember stumbling across Ellman's biography of Yeats quite by coincidence while on holiday somewhere. I didn't get a chance to read the whole thing but oddly enough I was just then trying to memorize 'Byzantium' without really knowing what it meant. One of the strongest coincidences of my life.

Stumbling across this post is another coincidence because I was just contemplating another attempt on 'Ulysses'. Now I will!

I am reading it right now, two hundred pages in and loving all of it. There is frustration for Ellmann shines a light on those often confusing lines that I was sure had a hidden meaning, and they do. So I find myself looking forward to reading the whole Joyce canon again. It is true, Joyce made ordinary extraordinary and back again. Step into Sweny's and you step onto the pages of Ulysees, Portrait, Dubliners, and Ellmann's biography. I found Joyce late in life, studying for my BA, and was smitten from the first read, even though I understood little. The second reading was more profitable as I followed Bloom across the city, talking to himself, digging out resentments, railing at shadows never seen. Nothing has come close for richness, perhaps Proust, but the length of In Search can take the edge of the reading at times. Joyce never lets you go, and so far I have found that with Ellmann. Thank you for sharing your thoughts.