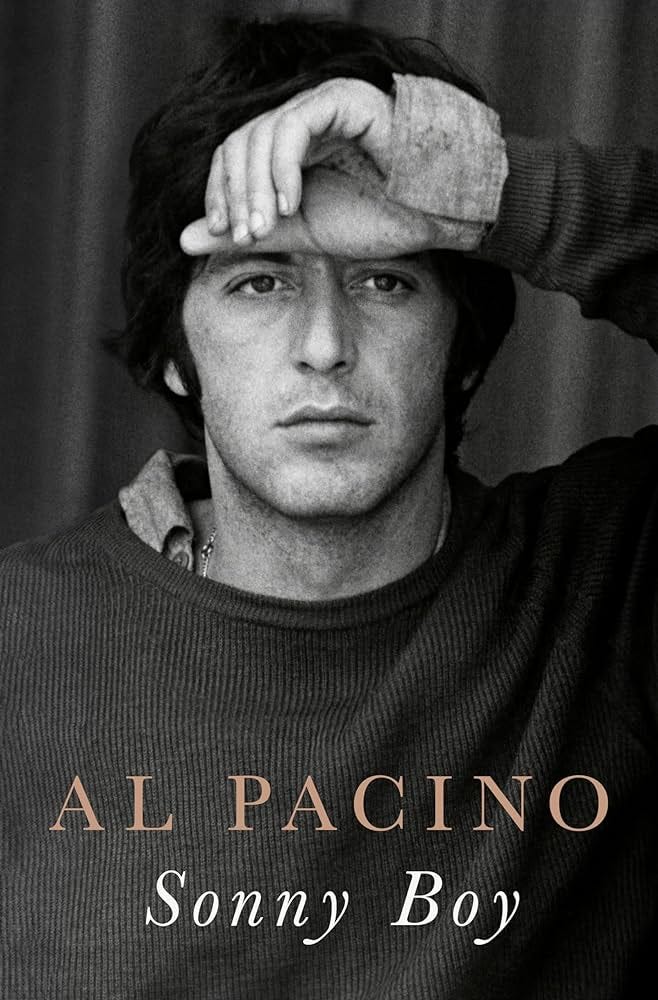

I didn’t open Sonny Boy with great expectations. If I want a memoir that reaches the heights of literature, I can always reread Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That, Nabokov’s Speak Memory, or the best example of experience transformed into art, Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. I was hoping for something like Ingrid Bergman’s My Story: a tale short on the getting-there and long on the once-arrived, which is the reason we read these in the first place. I’d even be happy if it was like Ernest Borgnine’s Ernie: a string of anecdotes with Tom-Wolfe-like Cosco-quantities of exclamation points. (“They told me I was going to have to kill Frank Sinatra! I couldn’t believe it! Me—a kid from Connecticut!”) But learning that Dave Itzkoff was the ghostwriter raised my hopes: he’s a published author with a long resume and I had interviewed him in 2021 about his terrific Mad As Hell, a biography of Paddy Chayefsky and look at the making of Network. He knows his way around a movie theater and a keyboard and I assumed that he would record Pacino speaking and then fashion it into a book.

But the overall effect of Sonny Boy reminds me of what Churchill is said to have remarked to a waiter: “Take away this pudding. It has no theme.”

The strangest thing about Sonny Boy is that it’s better as a coming-of-age story than it is about life as a universally-praised actor or the roles that made him famous. It should be, if not sweetness and light, at least filling, but it’s a bowl of themeless pudding. This is Al Pacino, he’s eighty-four, we have grown up watching him, he’s worked with everybody, and he’s one of the last great movie stars, the likes of which we will never see again. That whole era of movie stars who were also great actors is over—and don’t start up about Benedict Cumberbatch.

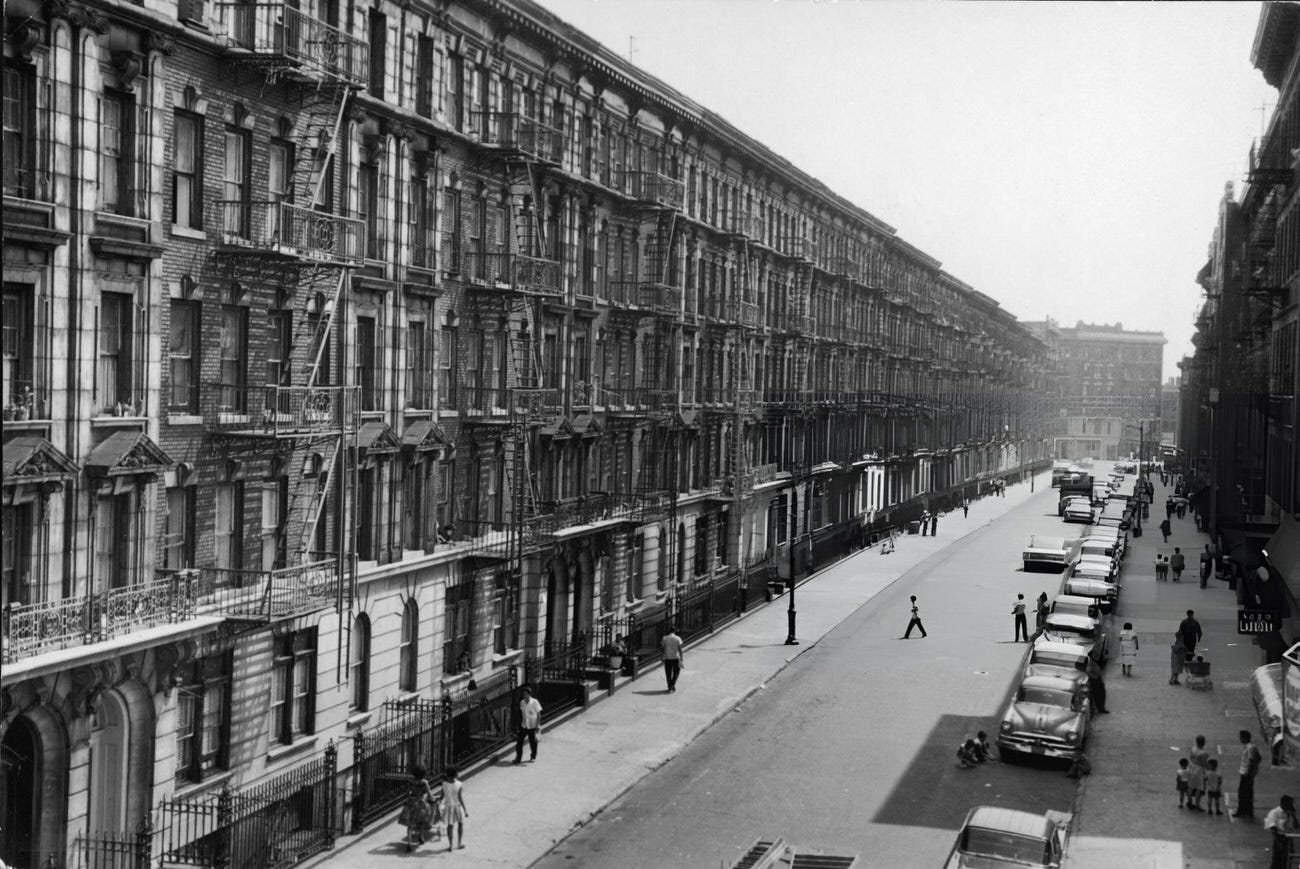

Sonny Boy begins well enough, with Pacino telling us about growing up in the South Bronx with a gang of wild friends and the freedom to roam the streets that kids today will never know. He hears his friends in the street calling for him and “gathering for another round of escapades.” We get a fine retelling of these, some amusing (a homemade gun) and some disturbing (sexual abuse). He acknowledges that many people, especially his mother, looked out for him. “I was not exactly under strict surveillance,” he says, “but my mother paid attention to where I was and in a way that my friends' families didn’t, and well knew it. I believe she saved my life.” When the economist Thomas Sowell, at the age of eighty-five, asked his elderly aunt how old he was when he began to walk, she told him, “Oh, Tommy, nobody knows when you could walk. Somebody was always carrying you.” We get the same impression about Pacino, who gratefully acknowledges everyone who helped him along the way.

We get his epiphany about the power of acting, too. In his early teens, he saw a local production of Chekhov’s The SeaGull in a theater designed for two thousand people; all but fifteen seats were empty. This was the moment where his mind was set afire. But he can’t recreate his engagement with the play the way that Joyce does with young Stephen Dedalus discovering the rhyme of “farewell” and “bell” or that his spelling book exercises contain hidden meters:

Wolsey died in Leicester Abbey

Where the abbots buried him

Canker is a disease of plants,

Cancer one of animals.

All we get is, “It affected me deeply.” Pacino began reading Chekhov to the point where “he became a friend of mine” and one thing led to another. He studied acting and got an Obie for The Indian Wants the Bronx, his first film lead in The Panic in Needle Park, and then we all know what happens next.

The problem is that this is where the pages should distinguish themselves from the thousands of others covered with ideas, analysis and recollection of The Godfather. We get mostly stories we already know. Paramount didn’t want him. Coppola had to fight for him. The dailies didn’t show Pacino “acting” much, but that was because Pacino was holding back and emphasizing Michael’s desire to seem aloof: “That’s my family, Kay. That’s not me.” There’s a story that Coppola moved the shooting schedule ahead to film Sollozzo’s murder earlier so that he could show it to Albert Ruddy and others at Paramount. We do learn that Pacino almost went his whole life without seeing The Godfather from start to finish: “Maybe I felt that because I was in it, I wouldn’t be a good audience for it.” Maybe there’s also something of the feeling we all get when we hear our voices played back on a phone message or see ourselves on video. Even someone as charismatic as Pacino might cringe a little. We also get this, however, which is at least refreshing:

I recently watched The Godfather at a screening for its fiftieth anniversary at the Dolby Theater in Hollywood, where a restored print was beautifully projected, with crisp, perfect sound. The whole experience was so uplifting. There's not a scene in the film where there aren't two or three things going on. There's not a dull moment in it, it's constantly telling a story.

It’s good to know he likes the movie as much as we do and for the same reasons.

But admiring The Godfather is nothing special and this tone of an eminently safe memoir is sustained throughout the book. Everything is very close to the vest, as if Michael in Godfather II were writing it. We hear about his romantic partners (he never married) and children almost secondhand. One moment, he’s with Jill Clayburgh or Diane Keaton or Beverly D’Angelo; a few pages later, there are new relationships and kids who the reader can never count or visualize. He makes asides like, “The drugs and alcohol didn’t help,” and we think, “Wait–when did that all become a problem? Did I miss something?” And this lack of concrete language when talking about himself is one of the book’s limitations. Strunk and White tell us to write with nouns and verbs that the reader can visualize, but there are many paragraphs like this one where he talks about rewatching 1977’s Bobby Deerfield:

I think part of the reason I was afraid to revisit it was because I thought it would remind me of what I was personally going through at the time. But when I saw years later I recognized someone who was exorcising himself using the medium of his work. I did put a lot of my own turmoil into the character where I thought it would be appropriate. I was grateful that I could put that to use, but I could have used a little more objectivity, which might have helped to draw in a larger audience and make it more appealing.

Read that and tell me what you picture in your mind’s eye. As David Byrne sang, “You’re talking a lot, but you’re not saying anything.”

We never even learn about the movies he enjoys. Wouldn’t it be interesting to know his favorite twenty or thirty or fifty films, even if they were simply listed without explanation?

This underwhelming feeling reminded me of what I felt in 2011 when I saw Pacino speak at a local theater. He was on tour to recoup some financial losses (which are, as with other topics, mentioned in passing) and I was looking forward to hearing him tell stories about his work. I’m too young to have seen A Conversation with Cary Grant, but this would be a close second—except that it wasn’t: Pacino was occasionally charming and loud, but all he wanted to talk about was Wilde Salomé, which had just been released and which nobody cared about—even me, who still defends Looking for Richard. “These seminars paid me well,” Pacino states. “If I did one a month, I got through the month. It was a way to earn a living.” I had missed out on seeing him in The Merchant of Venice because I couldn’t spring $300 for a ticket and never got the chance to see him in China Doll (2015), which was, by all accounts, a disaster which David Mamet rewrote while it was in production and for which Pacino used teleprompters, which he praises in the book as great tools for an older actor.

Sonny Boy is like the earth as described in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: “mostly harmless.” For the memoirs of the man who played Michael Corleone, Frank Serpico, Sonny Wortzik, Tomy Montana, Ricky Roma, Vincent Hanna, and Satan, it’s very sanitized. Maybe that’s a testament to the power of acting: the real guy isn’t anything like these people.

I heard him in an interview and got the same feeling - his real work is in his movies, he’s not that articulate about his life. I’ll probably give this book a pass.