This essay accompanies this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics, a podcast that often breaks the promise of its title but never wastes the listener’s time. The post and the podcast complement each other. We take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over three hundred episodes that you can find on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts. Check out the back catalogue for episodes on your favorite films—or give us some you’d like us to cover. Please subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts and consider leaving a review on your platform of choice. Thanks.

We all have people in our cinematic lives that irritate us and whom millions of other people find hilarious, talented, or thrilling to watch. We can’t stand the sight of them. Yet we also often have difficulty articulating our strong dislikes. Others will express amazement at these reactions, but the irritation holds because it’s not based on empirical observations or data, like arguing over athletic performance or whether or not a city is more dangerous than it was in the past. It’s wholly emotional, the cinematic equivalent of not liking someone at work because they simply rub you the wrong way; it’s what’s expressed when Caesar says that Cassius has a “lean and hungry look”; it’s the idea behind Tom Brown’s famous rhyme from 1680:

I do not like thee, Doctor Fell.

The reason why I cannot tell;

But this I know, and know full well,

I do not like thee, Doctor Fell.

Tony Curtis is one such figure, the kind of actor that many film fanatics regularly dismiss. I’ve been told by people whose tastes are in near-lockstep with mine that he’s terrible, talentless, unwatchable, and hammy. I mention Sweet Smell of Success and am told that Alexander Mackendrick, Clifford Odets, and Ernest Lehman are responsible for the movie’s quality. This continues through his career—and when I pull out the most obvious comeback, Some Like it Hot, that always gets brushed away as a one-off, a fine performance only because of the screenplay and director, like Burt Reynolds in Boogie Nights or Charlton Heston as the Player King in Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet. We’ve all heard the story of Howard Hawks watching the dailies of Red River and exclaiming, of John Wayne’s performance, “I didn’t know the big son of a bitch could act.” Curtis’s standing to some is epitomized by Stony Curtis, who gives Wilma Flintstone goosebumps. And we all—fans and foes alike—smirk at the famous interchange in Spartacus between Curtis and Lawrence Olivier, when we hear Olivier’s reedy, restrained voice (or Anthony Hopkins’s perfect imitation of it) contrasted with what comes from Curtis. You can take the boy out of New York, etc.

The biggest Curtis-haters also need to address his performance as Albert DeSalvo in The Boston Strangler (1968). This is a performance (and film) that never seeks to explain why someone is the way he is or does what he does; it’s the opposite of The Silence of the Lambs, Prisoners, Peeping Tom, Psycho, or a hundred other serial killer movies we’ve seen, in which the evil that men do is explained and then, at least in the world of the movie, contained. We watch, go through the clues, diagnose, understand, and restore order. That never happens in Richard Fleischer’s film; the movie that The Boston Strangler most resembles is Zodiac, David Fincher’s 2007 look at the ways a nameless, faceless killer terrorized San Francisco a few years after Albert DeSalvo did the same to Boston. Like Fleischer, Fincher wants to get his audience to feel like the city in which the film is set. In an interview for American Cinematographer, Fleischer said he used split-screens “to show the mood of terror pervading the entire city” and to give the audience “the feeling of the whole city being involved at the same time.”

Even more remarkable is that Curtis isn’t in the first half of the film. Everybody in 1968 who bought a ticket knew that Tony Curtis was playing the title character, but Fleischer built up his entrance much like Carol Reed did for Orson Welles in The Third Man. Welles—never modest about his own talents—gave credit for his famous entrance to the setup, noting that, in the theatre, “the old star actors never liked to come on until the end of the first act.” He told Peter Bogdanovich:

Mr. Wu is a classic example—I’ve played it once myself. All the other actors boil around the stage for about an hour shrieking, “What will happen when Mr. Wu arrives?,” “What is he like, this Mr. Wu?,” and so on. Finally a great gong is beaten, and slowly out over a Chinese bridge comes Mr. Wu himself in full Mandarin robes. Peach Blossom (or whatever her name is) falls on her face and a lot of coolies yell, “Mister Wu!!!” The curtain comes down, the audience goes wild, and everybody says, “Isn’t that guy playing Mr. Wu a great actor?” That’s a star part for you.

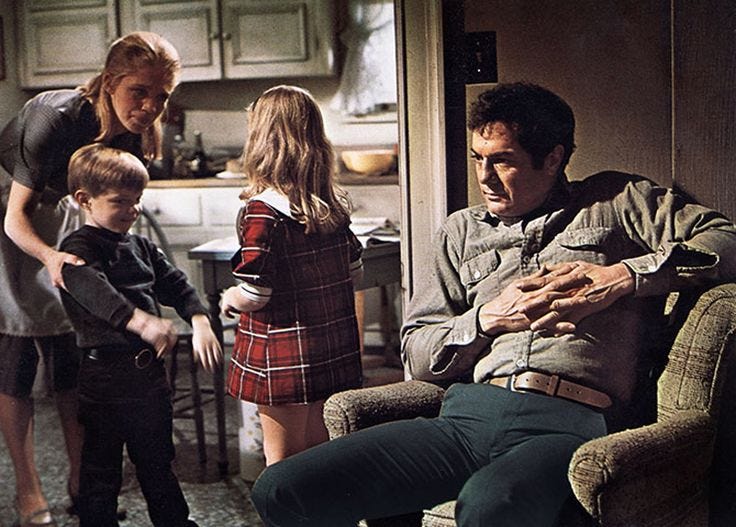

The same thing happens in Strangler. But when it does, we don’t see Curtis trying to talk his way into an apartment or with his hands around a woman’s throat: we see him at home, with his family, watching JFK’s funeral like any other Bostonian. He looks like a Teamster, not a killer–which makes it an even better entrance. We’re primed to read into his face everything we know about his psychopathology and immediately begin looking for signs, yet we are stonewalled. He doesn’t have a tic or a temper. He just sits there—which, of course, makes the entrance that much better.

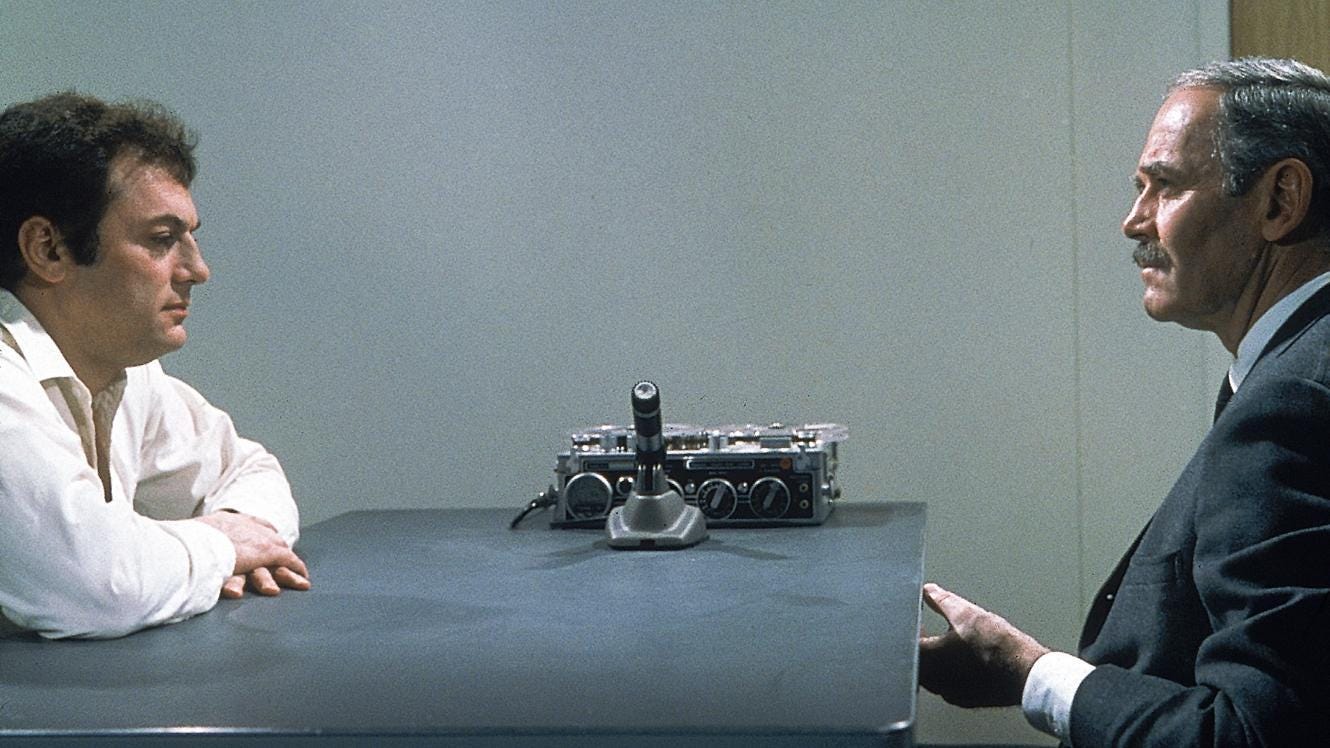

Curtis makes up for lost time. In the film’s most horrific scene, he attacks Sally Kellerman, but Fleischer knows just how much to show and what to leave to the imagination—the opposite of what Hitchcock does in Frenzy, when we see an attack in such well-lit detail that we are repulsed more than frightened. His final scene with Henry Fonda, who has been chasing him for the entire film, is like a self-contained one act play in which we see a man as unable to explain his actions as others are to explain why they don’t like Tony Curtis. And then, as with Zodiac, the film stops rather than ends. We’re informed (by onscreen titles):

ALBERT DESALVO, PRESENTLY IMPRISONED IN WALPOLE, MASSACHUSETTS, HAS NEVER BEEN INDICTED OR TRIED FOR THE BOSTON STRANGLINGS.

THIS FILM HAS ENDED, BUT THE RESPONSIBILITY OF SOCIETY FOR THE EARLY RECOGNITION AND TREATMENT OF THE VIOLENT AMONG US HAS YET TO BEGIN.

In other words:

YOU JUST ENJOYED WATCHING A THRILLING POLICE PROCEDURAL , BUT WE HOPE THAT ONE DAY THE GENRE IS NO LONGER RECOGNIZED. BUT NOT REALLY. WE HAD TO SAY SOMETHING.

The film makes halfhearted attempts at claims of historicity, but doesn’t need it. We don’t really assume that we’re watching the true story of Albert DeSalvo any more than we assume we’re getting the real story of the Wars of the Roses by watching Richard III. What we’re watching is a portrait of a man who refracts all of the rays of light we shine on him: we watch, but can’t penetrate the mystery.

Besides Tony Curtis, The Boston Strangler has much to recommend it. Watching George Kennedy and Murray Hamilton as the detectives living on bad sandwiches, cold coffee, and Lucky Strikes makes you wish they had made other films in this vein. Henry Fonda plays the decent type to which we’re accustomed, a point of entry into a world as strange as Fleischer’s Boston. William Hickey has a small part as a man so disturbing that, for about ninety seconds, you’ll think, “Wait—I thought Tony Curtis was the killer.” There are many scenes with split-screens that will make you wonder why this technique has fallen out of fashion. The suspense is well-maintained: despite our knowing that Curtis will be caught, there’s great tension in how this happens.

But ultimately, it’s Tony Curtis’s movie. We can laugh at Antoninus all we want, but nobody is chuckling here.

At The Arch cinema in Cobh County Cork in 1954, I saw Tony Curtis in The Black Shield of Falworth. I remember being amused by the American accents in what was supposed to be the England of Henry IV.

That guy playing Godot is a great actor.