Here’s a post based on this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics and a player that can let you listen to an ad-free version of the show. We choose the films almost at random: one of us will watch (or rewatch) something and text the other guy. We then record without any previous conversation, recreating the enthusiastic conversations people have in their cars on the way home from the theater. We also take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over 275 and you can find them all here. You can subscribe to the show wherever you get your podcasts; please consider leaving a review on your platform of choice. Thanks.

Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson contains one of Johnson’s most-quoted remarks about life as a sailor: “No man will be a sailor who has contrivance enough to get himself into a jail, for being in a ship is being in a jail, with the chance of being drowned.” Just to make sure Boswell isn’t missing the point, he adds, “A man in a jail has more room, better food, and commonly better company.” But elsewhere in that cinderblock of a book we read this:

We talked of war. JOHNSON. “Every man thinks meanly of himself for not having been a soldier, or not having been at sea.” BOSWELL. “Lord Mansfield does not.” JOHNSON. “Sir, if Lord Mansfield were in a company of General Officers and Admirals who have been in service, he would shrink; he’d wish to creep under the table.”

Johnson defines “mean” in his 1755 Dictionary as “contemptible; despicable,” which is exactly how he means it here. Men can look back on their lives with satisfaction or justifiable pride, but in their innermost hearts they think—know—that they still never did what the guy who lives three houses away did in the la Drang Valley or what their father’s now-chubby and balding friend did at Inchon. After finishing your personal best workout, you still never passed basic training; after closing the biggest deal for your firm, you still never spent a day as one of the thousands of sailors on an aircraft carrier; and after watching Saving Private Ryan for the tenth time, you still never faced any genuine danger. If Captain Miller came over for dinner, you’d be telling Lord Mansfield to make some room under the table. If I had to watch Das Boot alongside my wife’s cousin, who served on a nuclear submarine, or The Battle of Britain with the fighter pilots I once met, or The Hurt Locker with a former student of mine who did five combat tours as a Ranger, I wouldn’t be in a hurry to yap about my Substack.

That feeling that sailors, soldiers, airmen, and Marines trigger in others who never served is the battery that charges Master and Commander. It’s impossible to watch it and not wonder how you would have fared on a ship of the line in 1805 when (as the opening title tells us) “Oceans are battlefields.” We would want to be there for the adventure of it all: after a boy plants a lamp on a decoy sail to trick the French and is hoisted back onto the deck, Captain Aubrey (Russell Crowe) tells him, “Don’t tell me that that wasn’t fun!” But we’d pass on being that same boy when his arm is amputated. What the movie shows us is that the fun and the amputation are part of the same literal and psychological voyage. The crew of the Surprise is tough in all kinds of ways that most viewers aren’t.

One of the reasons the crew of the Surprise and the hypothetical veterans mentioned above are as tough as they are is because of those who have commanded them. Master and Commander may be one of the best films about leadership, belonging high on a list that includes Patton, Miracle, Henry V, and The Bridge on the River Kwai. Captain Jack Aubrey possesses the confidence and charisma that every leader needs. There are smarter people (and Vulcans) than James T. Kirk aboard the Enterprise, but there’s no question of Kirk’s ability to get even the constantly-whining Scottie to perform. Aubrey is the exact opposite of every Michael Scott clone for whom you’ve worked (or work now)—and we all know these people who opine about their leadership “style,” have half-read copies of Leaders Eat Last and The First 90 Days on their shelves, and hang terrible “motivational” posters about “DETERMINATION,” “GOALS,” and other abstract nouns in the hallways and break rooms.

Aubrey doesn’t pontificate about leadership; he exemplifies it. After the boy loses his arm, Aubrey visits him in sickbay to give him a book about Nelson, who is to Aubrey what Aubrey is to him (and us). It’s the naval equivalent of Babe Ruth visiting Johnny Sylvester but Aubrey does it without fanfare. And when he has to make a hard decision, he never forms a committee (again, think of your day job) or suggests they “put a pin in it,” or forwards an email with copies sent to people who don’t understand the issue, or asks, “Well, what are the other commanders on the other ships doing? Maybe we can connect?” When Aubrey learns that the Surprise will sink if the ropes towing a fallen mast—and the hapless sailor entangled them—aren’t cut, he orders the ropes to be cut and is significantly on the scene, hacking at them himself. When a carpenter’s mate fails to salute the universally-despiesd midshipman Hollum, Aubrey has the mate flogged, despite the punishment seeming to far exceed the crime. Aubrey always draws upon his experience and fundamental values—not what he saw in a PowerPoint—to do what he knows is best for the crew, whether or not they agree with him.

Yet there are moments in which Aubrey reveals his assumptions about command. He tells Hollum, “Don’t make friends with the foremost jacks, lad. They’ll despise you in the end and think you weak. Nor do you need to be a tyrant. You have the knowledge. Find the strength within yourself. Without strength, true discipline dies by the board.” He also tells a story about Nelson that, in any other movie, would be ironic or, at best, ambiguous: “Someone offered him a boat cloak on a cold night. And he said no, he didn’t need it. That he was quite warm. His zeal for his king and country kept him warm. I know it sounds absurd, and were it from another man, you’d cry out, ‘Oh, what pitiful stuff’ and dismiss it as mere enthusiasm. But with Nelson ... you felt your heart glow.”

You felt your heart glow is as close a description as I can give about admiring Aubrey in action. This feeling he engenders—this glowing heart—is why his men are so fierce and fight so well against the crew of the Acheron when they board it. Their secret ingredient is loyalty, not testosterone; that Aubrey is next to them, also disguised as a whaler, may violate protocols but rouses his men all the more. In Macbeth, we see the effects of bad leadership when we learn that those Macbeth commands “move only in command–nothing in love.” People will comply, but compliance doesn’t win any battles.

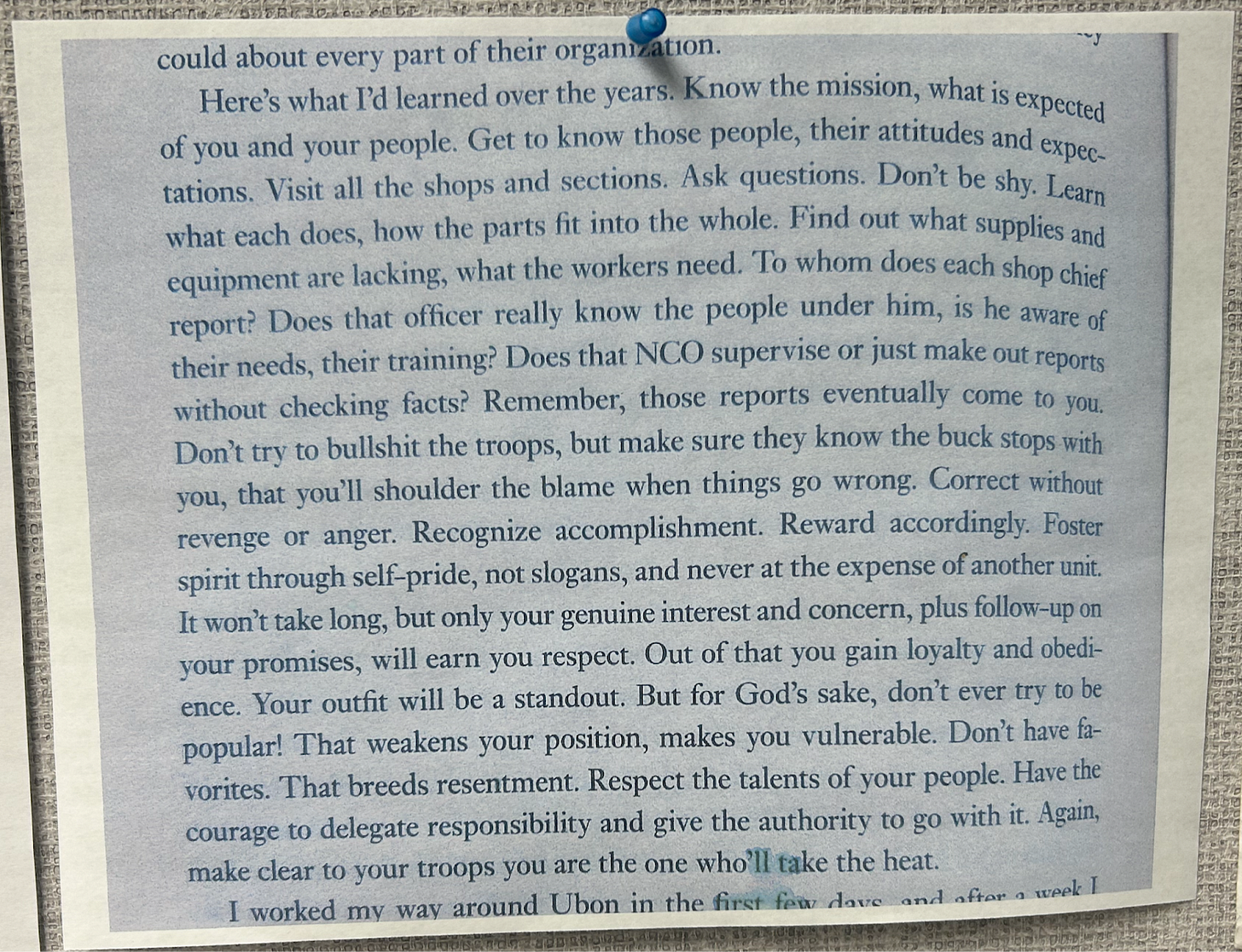

One of the best books I read last year was Fighter Pilot, the memoir of triple-ace Robin Olds (1922-2007). An “ace” is a pilot who has shot down at least five enemy aircraft: Olds had 17 in World War II and Vietnam. The book is a sprawling look at his life and career, which saw Olds rise through the ranks of the USAF to brigadier general. Like Aubrey, Olds commanded hundreds of men but doesn’t talk much about his theories of leadership—until one small passage, almost buried in the 500-page narrative, in which he directly states his ideas. I copied it from the book and hung it on my bulletin board:

The Captain of the Acheron may have a more technologically advanced ship, but he’s never read or thought anything like this; his posing as a surgeon to avoid capture is a low to which Aubrey would never stoop.

This business of not talking too much about one’s theories of leadership (or of anything) is manifested in the ways in which the men aboard the Surprise address each other. Sailors here say “mister” more often than characters in a Springsteen song; they joke with each other, but not between ranks. In a scene near the end, in which Aubrey tells First Lieutenant Tom Pullings that he will be the new Captain of the captured Acheron, Tom is obviously surprised but gets himself together in a second. He thanks Aubrey and they shake hands. That’s it. In others’ imaginations, this could become sentimental or an occasion for Tom to tell Aubrey how much he admires him or Aubrey to tell Tom what a great future he has in store. But neither of them has to say anything: the action, not the word, is what counts. What looks like restraint and a tamping-down of emotion actually makes the emotion more pronounced and meaningful. This is why long conversations about “leadership styles” at work are often dominated by the worst leaders among the staff; it’s why forced merriment at office parties makes us cringe instead of bond. In both cases, we see simulations of the qualities people pretend to possess, but don’t.

Aubrey is the boss you wish you had and the Surprise is where you wished you worked.

If reading this makes you curious about the books the film is based on, I’ve been writing about them for a while:

https://joshuacorey.substack.com/p/master-and-commander

The books are so much better than the movies.