Here’s a post based on this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics. We choose the films almost at random: one of us will watch (or rewatch) something and text the other guy. We then record without any previous conversation, recreating the enthusiastic conversations people have in the cars on the way home from the theater. We also take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over 250 and you can find them all here.

There was a man in the land of Uz, whose name was Job; and that man was perfect and upright, and one that feared God, and eschewed evil. There was also a man in the land of Minnesota, whose name was Larry, and that man was reasonably perfect and upright, and one that feared God, and eschewed evil.

And there are many men in many lands who find themselves, to some degree, in the same boat as Job and Larry.

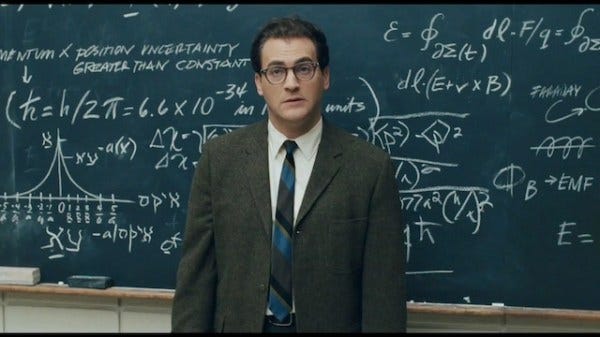

A Serious Man (2009) may seem much different from the Coens’ adaptation of No Country for Old Men, which they released two years earlier. But they both concern a likable man who finds himself posing questions that the universe—or any of its wisest men—cannot answer. And even if there are glimpses of answers to the questions What does God want? Why are these things happening? or What is the right way to respond to events? neither forties-something Larry or late-sixties Sheriff Bell can read the writing on the wall (or, in the case of A Serious Man, the writing on the teeth). The film begins with a quotation from Rumi, “Receive with simplicity everything that happens to you,” and we watch Larry try to do this and remain in a static almost-laugh the whole time.

Larry Gopnik is a Minnesotan Jew who tries to be a serious, upright, and God-fearing man, but finds himself being tested in ways that provoke a metaphysical quest for answers. Listing all of his troubles would take several paragraphs, but think of an example of any human struggle, small or large, and you’ll find Larry trying to deal with it. As Polonius praises the players who visit Elsinore as “the best actors in the world, either for tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comical, historical-pastoral, tragical-historical, tragical-comical-historical-pastoral, scene individable, or poem unlimited,” Larry experiences every kind of tsuris in every combination.

The dark comedy of the film relies on its compression. Everything that could happen to a person over the course of a long life happens to Larry in the span of a few weeks. This is the same setup that makes After Hours so perfect1 and both films create the same effect, putting the viewer in the headspace of the lead character, who seems to find links between clues that he can’t decode. When Griffin Dunne drops to his knees on an empty Manhattan Street and yells, “What do you WANT from me?” he’s in the same headspace as Larry visiting the rabbis and the viewer watching the films, looking for ways that events are connected but knowing, long before the characters, that these connections will be only be jokes. There will be half-answers that provoke only further questions.

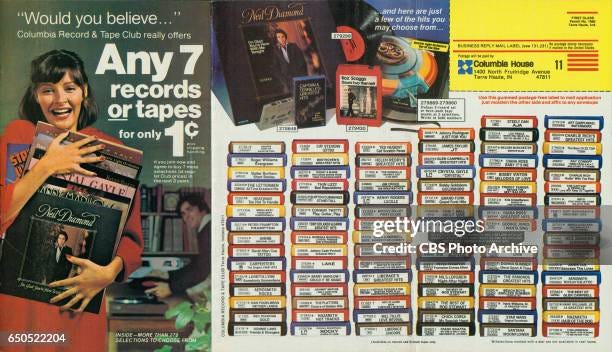

One of the film’s running jokes echoes its larger issues: Larry’s troubles with The Columbia Record Club are a microcosm of his existential struggles throughout the film. Beginning in 1955, the CRC did with LPs what the Book of the Month Club began doing in the in 1926: “subscribers” were offered, each month, a main selection that would be automatically shipped to them and for which they would be charged if they did not return a postcard indicating that they didn’t want it or wanted something else. The premise was that these clubs were staffed by tastemakers who would cull the vast array of published and recorded material and find what every middlebrow reader would want on his shelf or hi-fi.

I am old enough to remember joining the CRC by a means that seems wonderfully retro: we’d receive a mailing that contained hundreds of postage-stamp-sized album cover replicas, which we would tear at the perforations, lick (again, like stamps) to a card, and then taping a penny to the card before mailing. The penny idea was brilliant and appealed to the desire to get something for nothing: we’d be getting seven records for one cent and only had to buy four more in the coming year! I repeated this process with the Columbia Video Club, the Paperback Book Club, and the Science-Fiction Book Club all throughout grade school and college. Of course, I often ended up not returning the card in time, or doing so too late for me to avoid getting an unwanted album or book the next day and wouldn’t go through the hassle of returning it. They saw me coming a mile away.

The whole idea of a “negative response,” in which doing nothing is actually doing something, sounds like it comes from the mind of Samuel Beckett and has caused so much tsuris for consumers that the FTC has issued guidelines for its use. And the same trouble is seen today in recent calls by the FTC to make canceling subscriptions to online services as easy as it was to begin them.

So when Dick Dutton from the CRC calls Larry and asks why he hasn’t paid for Santana’s Abraxas and Larry replies, “But I don’t want Santana’s Abraxas—I didn’t do anything!” Dick Dutton replies, “That’s the point.” Dick Dutton is the voice of Hashem, telling Larry that it doesn’t matter what he did or didn’t do. He now has a bill, regardless of whether or not it’s just or if he wants to pay it. That’s the human condition and response to tribulation: having to pay for something—with money, time, or even more precious commodities—for which you never asked. “Even today is my complaint bitter,” Job laments, saying of God, “Oh that I knew where I might find him! I would order my cause before him, and fill my mouth with arguments.” But you can’t argue with the CRC.

However, a throw-up-your-hands nihilism isn’t the only response to events; the film doesn’t settle for an easy answer found on cheesy T-shirts from the 1980s. The universe may throw random things in our paths and we might, as the film’s epigraph by Rashi advises, receive these things that happen to us with simplicity. But we are also teased into thinking that we can decode things just enough to grasp some kind of understanding. Larry has to adjust his TV aerial; this is the fiddling he does on the roof. As he’s looking for a signal so that his son can watch F-Troop, he’s also looking for a signal from Hashem about the meaning of his troubles.

He asks three rabbis for their help and each of their ages suggests where they are on the road Larry is traveling. The junior rabbi offers him nothing but platitudes: he tells Larry to “change his perspective” and realize that even the parking lot can be a source of wonder. “The boss isn’t always right,” he says, “but he’s always the boss.” The middle-aged one tells him a story about a dentist who saw Hebrew letters reading “SAVE ME” on the inside of a goy’s teeth, was so troubled by them that he launched a dental and philosophical inquiry, but eventually gave up trying to figure out why they were there and went back to his routine. And the third, the ancient Rabbi Marshak, cannot talk to Larry because he is too busy sitting still at his desk. “The rabbi is thinking,” his secretary explains.

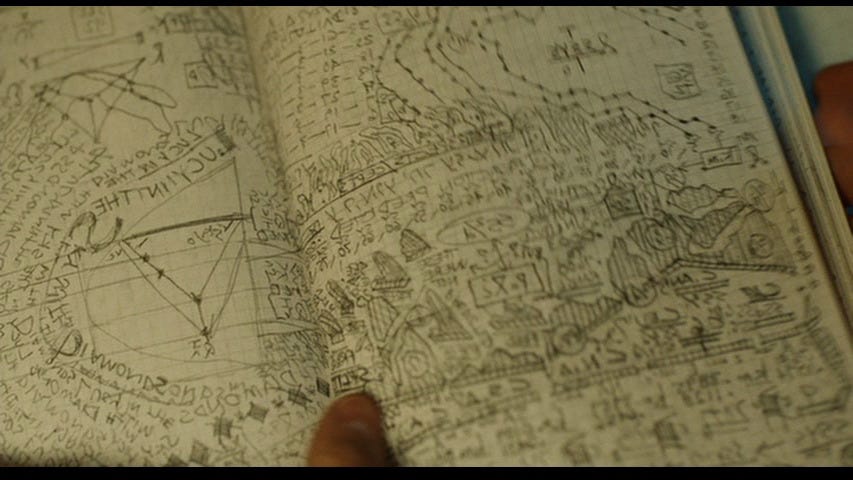

But even if Larry were given the key to the universe, what would he do with it? His brother Arthur (Richard Kind, who wonderfully plays the same role every time he appears in anything) has created The Mentaculus, a book containing a “probability map of the universe.” When Larry reads it, he sees what a character in Flannery O’Connor would call “evil gibberish.” Arthur uses this cracked code of the universe, this glimpse into the mind of Hashem, not to gain wisdom but to win at local card games. This is another part of the human condition. We may say that we want to really understand how the universe works, but are we simply saying so in order to sound like deep thinkers? If we did, what would we do? The film Primer (2004) concerns two engineers who create a bonafide means of time travel, but who use it to go back to the start of a trading day and make investments they know will pay off. Our imaginations couldn’t handle the smallest taste of Hashem’s direct speech. We’re all Tom Cruise being told by Jack Nicholson that we can’t handle the truth.2

Yet we try.

C. S. Lewis—who, like the Columbia Record Club knew all there is to know about human fallibility—reminds us that our desire to know the mind of God and have him enter our plane of existence in order to answer our questions may not be the most thought-out wish:

I wonder whether people who ask God to interfere openly and directly in our world quite realise what it will be like when He does. When that happens, it is the end of the world. When the author walks on to the stage the play is over. God is going to invade, all right: but what is the good of saying you are on His side then, when you see the whole natural universe melting away like a dream and something else—something it never entered your head to conceive—comes crashing in; something so beautiful to some of us and so terrible to others that none of us will have any choice left?

Perhaps using The Mentaculus to win at card games is Arthur’s best idea. Better to not swim into waters that are far too deep.

The film stops rather than ends—how could it otherwise? Rabbi Marshak has met with Larry’s son and has told him all that he knows. In 1986, Robert Fulghum sold millions of copies of All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten; Marshak seems to have learned all he needs to know from Jefferson Airplane. He asks the boy, “When the truth is found to be lies, and all the hope within you dies—then what?” What indeed! The rabbi—the teacher—tells him to “Be a good boy” and sends him on his way. Meanwhile, Larry’s luck seems to have changed: his son was Bar-mitzvahed, his brother has escaped to Canada, his romantic rival, Sy Ableman, is dead, and he was awarded tenure. Inspired by his momentary peace of mind and what he then thinks is his license set some small part of the universe right, he changes Clive’s fake passing grade of C to C-.

And then the phone rings. Larry’s doctor has some bad news. There’s also a tornado about to hit his son’s shul. While talking to Clive from his moral high ground earlier in the film, Larry says that “actions have consequences”—not just in physics, but morally. Was the phone call the consequences of the spiteful minus, one that the viewer endorses against Clive who tried to guilt and then bribe Larry into giving him a passing grade? Or, as we have all been told in Psych 101 a thousand times, is correlation not causation?

We want Hashem to reveal that He has ordered the universe and our lives like a well-made play, but often life seems as comprehensible as the plot of The Big Sleep: it seems to make sense, but there are events and elements that we cannot explain.

At the end of the biblical story, God speaks to Job from a whirlwind, asking Job a series of truly rhetorical questions to which the answer is obvious.

Who is this that darkeneth counsel

By words without knowledge?

Gird up now thy loins like a man;

For I will demand of thee, and answer thou me.

Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth?

Declare, if thou hast understanding.

Who hath laid the measures thereof, if thou knowest?

Or who hath stretched the line upon it?

Whereupon are the foundations thereof fastened?

Or who laid the corner stone thereof;

When the morning stars sang together,

And all the sons of God shouted for joy?

The whirlwind that approaches Larry’s life in the final moments doesn’t ask any questions, but speaks just as clearly about our inability to solve the equations.

It's also what drives Thomas Berger’s great novel Neighbors, where all that could happen between next door neighbors over the course of twenty years happens, in real time, from the moment they move in until things begin exploding. Read this if you never have. You’re in for a treat.

Besides, we all learned the meaning of life, the universe, and everything from reading The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

Thank you for another great podcast! That was by far the best analysis of A Serious Man I’ve ever heard. I love the movie, and both of you shared fantastic insights about it. Yet another reason why yours is my favourite film podcast out there. And I really enjoyed the essay that went along with it here. Keep up the great work!

This was a fantastic read! A Serious Man is my favorite Coen brothers film, and your thoughts on it are brilliant. Now you've made me want to see this masterpiece again. Might have to pair it with After Hours. :)