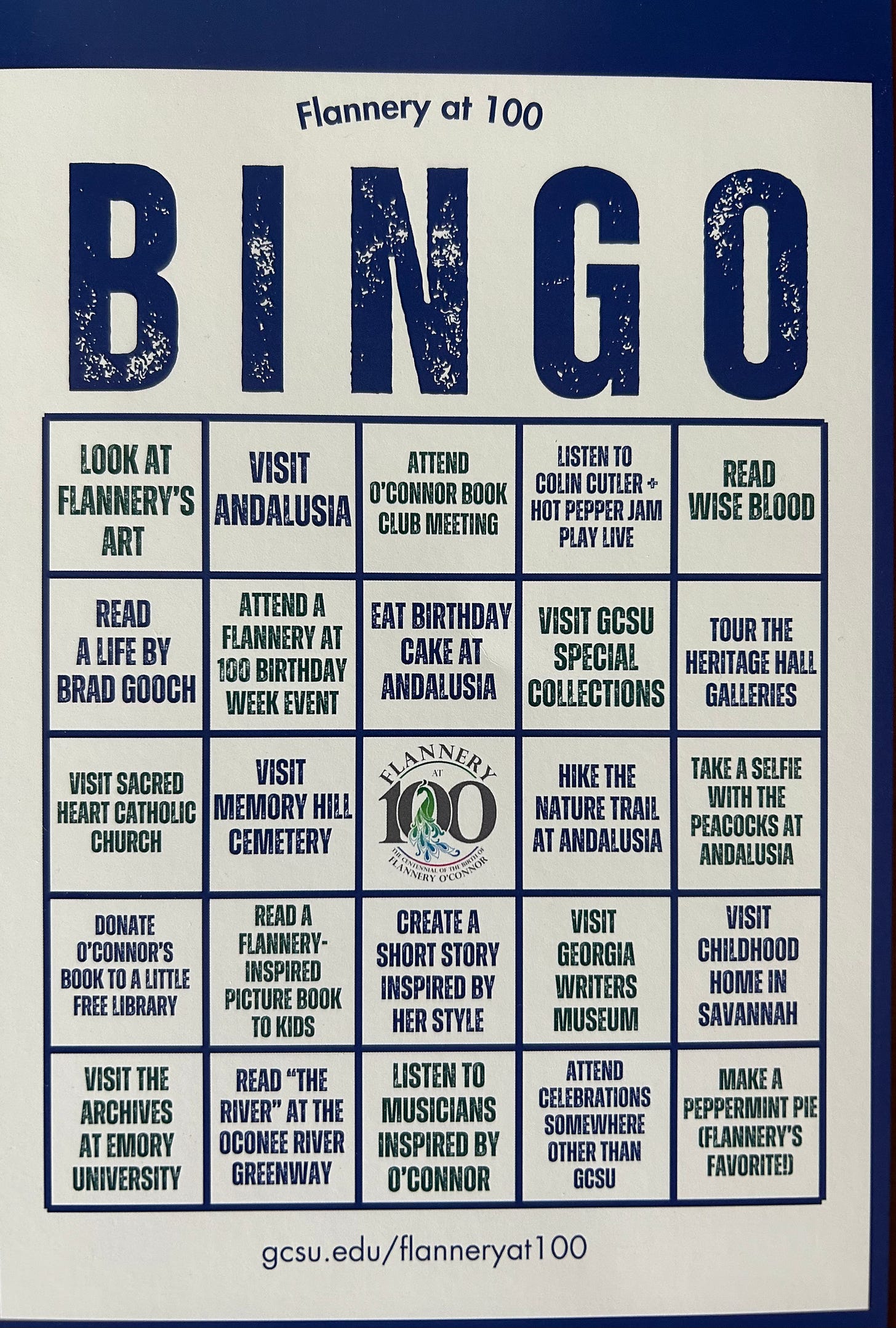

I am what my daughter calls a Flan-Fan. I have been reading the work of Flannery O’Connor for thirty years, wrote a book about her literary reputation, visited her childhood home in Savannah twice, spoke there once, but never thought I’d make it to Milledgeville, GA, the town to which she moved with her parents (with her father shuttling between there and Atlanta) in 1938 when she was thirteen and to where she took up permanent residence in 1951 when she was twenty-six. You can bring your kids or friends with you to see her childhood home in Savannah because you’re already in town, but Milledgeville is off all beaten paths, air travel routes, and highways. As Manly Pointer says of his birthplace, “It’s not even a place, it’s just near a place.” It’s for the true believers. I had always wanted to visit because I would be able to see Andalusia, the house and farm where she lived with her mother, Regina, until her death in 1964 at thirty-nine and from where she wrote almost all of the stories, essays, letters, and two novels that make up the O’Connor canon. I had seen all the photos of her room, her on the porch, the barn, the cow pond—and while I wanted to see it in person, it was more of a someday idea (like Lichfield) than a possibility. I knew that Savannah and Milledgeville would be celebrating her hundredth birthday on March 24, wished I could be in either place, and did my best to note her centennial by publishing an essay about her singular genius.

When I saw an email a few months earlier about travel grants from Georgia College State University to fund individual trips to Milledgeville, I applied and forgot about it, assuming that some other lucky applicants had received them. But on a Friday afternoon in February, I received an email from Jessica McQuain and Katie Simon at GCSU that I was awarded a grant. I didn’t have to do anything or write anything about it—just come to Milledgeville and dwell among the Flan-fans for the centennial. There was no catch. What follows is an account of my five days in Milledgeville: what I saw, who I met, and what I learned.

My time there was like a one-man retreat. I didn’t have a schedule other than for the events I wanted to attend. Even when traveling with one’s soulmate or friends, you still always negotiate your own desires with those of other people. To not do this for five days was strange. I had to grow into it. I could go for a run on the campus, then tour the Old Governor’s Mansion, walk around the city, get coffee, and sit on the street with my computer like a hipster, go read on the porch of Andalusia, and then decide where to have dinner. It was something like being a kid in the summer who is too young to work and every morning has the whole day ahead of him to do whatever he wants.

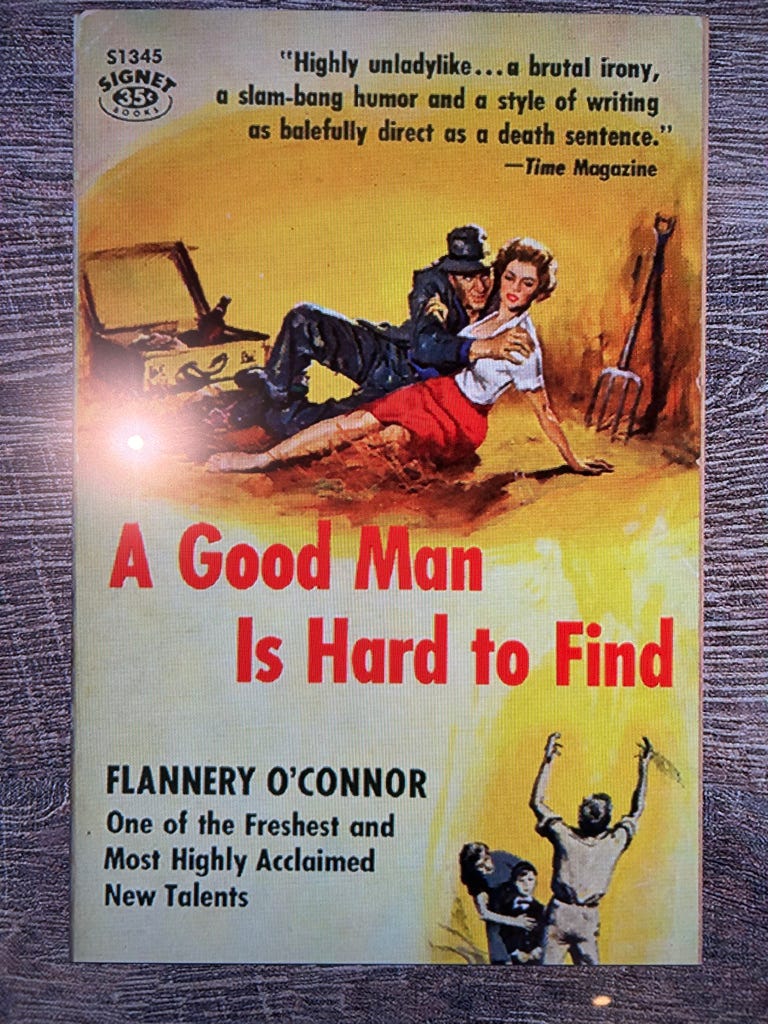

O’Connor wrote, “I am always having it pointed out to me that life in Georgia is not at all the way I picture it, that escaped criminals do not roam the roads exterminating families, nor Bible salesmen prowl about looking for girls with wooden legs.” As with so many other things, she was right about Georgia, too.

Andalusia

I began O’Connor’s hundredth birthday sitting in Newark airport before dawn, reading James C. Cobb’s Georgia Odyssey and eating jelly donuts. All I knew about Georgia I learned from O’Connor and I thought it would be interesting to learn more about the big picture surrounding small Milledgeville. My current town in New Jersey has a population of 47,000 and an area of 41 square miles; Milledgeville has 30,000 fewer people and an area half the size. A theme of Cobb’s book is There’s Atlanta and then the rest of Georgia and that people who live outside of the capital regard themselves “Georgian as Hell.” I wondered how the real Milledgeville would match the version in my head. Would I be a sore thumb, fielding questions about Tony Soprano?

After landing in Atlanta and finding my car, I was on the road. The sunlight was hitting the golden dome of the capitol building so hard that it looked like someone had plugged it in. I listened to parts of a seven-hour Flannery O’Connor playlist someone had put on Spotify and found that the further I got from Atlanta, the easier the drive, although at no point was driving in Georgia anything like driving in New Jersey, where everyone—new drivers, nuns, little old ladies—tailgates, weaves in and out of traffic and radiates anger that transfers like a virus from car to car. I drove east on 20 and then south on 441 until I reached the promised land. The hotel was across a busy four-lane highway from Andalusia. The guy who checked me in told me, “People don’t realize how important Flannery O’Connor is for this town” and then told me that Stan Laurel was also a Milledgeville native. I didn’t know that; I didn’t even know he was American. For some reason, I thought he was a Brit. (Turns out I was right: Laurel was a Brit; the desk clerk meant Oliver Hardy. Partial credit.) I went to the room and skipped my usual, admittedly odd step of putting all of my clothes in the drawers so that I could get over to the house.

Andalusia’s large trapezoid of an Interpretive Center opened in March 2023 and still looks brand new. When you enter, the gift shop is to your left and a large room filled with display cases and wall-sized timelines is on the right. The cases had objects like her teddy bear, a golf ball she drew her initials on (to make look like a bird), one of her childhood books, some of the things she wore as a little girl, and lots of photographs. Ping Zhu, illustrator of The Strange Birds of Flannery O’Connor had just finished speaking. I bought my centennial T-shirt and postcards. There was leftover birthday cake laid out (I had missed the singing at noon) and I had a piece. I had given up all of that stuff for Lent, but thought this was worthy of an indulgence.

The path from the Interpretive Center to the house rises up a hill and there are trees on the right through which you can see the house. I wanted to approach it slowly and not act like a kid getting in line for Space Mountain; I’d only get one chance to see it in person for the first time. It looked exactly like I imagined it: the reddish roof and awnings, the big porch, the brick steps—all were as I had seen them in a hundred photographs. It stopped me. Some would contend that this whole pilgrimage was sentimental, but it was more emotion than sentiment. Writers’ houses are not sacred, but they certainly have some aspect of what Rudolf Otto and later C. S. Lewis called the numinous—a sense that one is near something otherworldly that creates emotions difficult to articulate. The perfect weather, the small number of people on the grounds, the distance I had come, and the quiet of the landscape all combined to make my first look at the house different from a look a house.

I walked up to the porch and waited for the guide–a student at GCSU who met me and Dave, a guy from Savannah who told me he lived around the corner from O’Connor’s childhood home. We saw the first floor: the kitchen with its tiny two-seat table and the refrigerator with ice-maker that they bought after Flannery sold the rights to “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” to the Schlitz Playhouse, which starred Gene Kelly as Mr. Shiftlet. (She noted in a letter that she and Regina were excited about it: “While they make hash out of my story, she and me will make ice in the new refrigerator.”) The fridge has a pedal on the bottom to allow it to spring away from the wall for easy behind-the-fridge dusting, which made me wonder about the last time I cleaned behind my own. Our guide told us that Flannery saw the pedal as a booby trap that she sometimes sprung accidentally with her crutches. We saw Regina’s combination desk / command center with a print of Jesus on the wall signed by Pope Benedict XV, her uncle Louis’s room, and the dining room. When the guide spoke of the immense weight of the sideboard, Dave said it looked like it was built of German Black Forest wood. He said he only guessed that because he appraised antiques for a living. Later, I learned that he was in town because he had appraised O’Connor’s recently-discovered and finally-ready-to-be-revealed paintings discovered in the Cline house, also in Milledgeville, which was now filled with O’Connor materials and recently acquired by GCSU.

Of course, the room everyone wants to see is Flannery’s, also on the first floor so that she didn’t have to contend with the stairs. The first thing to notice is the pair of crutches and her desk in the middle of the room so that she could type with her back to the window. There’s a good moment in Wildcat where Regina tells her, “It’s nice you got this view while you’re writing—I’ll bet it helps,” but anyone who has ever tried to write more than two sentences understands why Flannery heroically turns the desk around so she can concentrate. (That, of course, is when the feathers rise.)

In a corner is the record player that the Dominican Nuns of Our Lady of Perpetual Help Home in Atlanta gave her for writing the Introduction to A Memoir of Mary Ann. Our guide told us that Flannery never liked music and as a proper Southern lady had to keep the gift, but kept it here in the corner. She added that the nuns made this gift because they had gotten a newer, better record player and that some of the records there were part of the gift. She received others from Catholic publisher and correspondent Thomas Stritch, telling him the records were a “a real boon” but also writing to another friend, “All classical music sounds alike to me and all the rest of it sounds like the Beatles.”

When the tour ended, Dave and I walked to the Hill House, where Jack and Louise Hill and their border, Shot, lived; these three African-Americans all worked on the farm and were part of Andalusia for the almost the whole time O’Connor lived there. Inside the Hill House there are some sheets of plexiglass over the walls to show the pieces of newspaper that were put between the breaks as insulation. It also had a bathtub about half the size of what you’d expect.

I looked for the peacocks and found two of them in a long coop. When Flannery lived here, she had over forty birds (asking, “Who counts after forty?”) but the peacocks are those most associated with her—and for good reason. Yes, there’s an ancient tradition connecting the eyes on the feathers to the eyes of God, but you can find a symbol for God almost anywhere if you aren’t being ironic. The peacock works here because it doesn’t apologize for its oddity, instead transforming what should be odd into a kind into grandeur. Read O’Connor’s letters or essays for ten minutes and you’ll find her voice to be the one a peacock would use if it could speak—or at least speak with words. The ones there now are not descended from Flannery’s; her last peacock, named Manly Pointer after “Good Country People,” already passed.

I visited the house almost every day, sometimes for an hour, sometimes longer. One morning there were two buses of high school kids in uniforms, there for a class trip. I wondered if growing up in Milledgeville made some kids resistant to reading her, having been told since birth that she’s the greatest. (It’s like how young people are told their whole lives that Citizen Kane is the greatest film ever made and then, when they finally watch it, there’s no way for the film to meet their expectations.) I sat on the porch reading “Enoch and the Gorilla” and when I walked away, one of them yelled across the pond, “Bye, Mr. O’Connor!” I thought that was pretty funny.

The Visual Artist

GCSU held a reception for the first public exhibition of O’Connor’s paintings and visual art. O’Connor claimed, “Nobody admires my painting much but me,” so she would have been surprised at the attention paid to these pieces, never meant (like her Prayer Journal) to be seen by so many people. We all knew about the cartoons she drew while working on the student newspaper at GCSU (then called Georgia State College for Women) as well as her famous self-portrait with a pheasant gamecock, but these seventy pieces were all newly-discovered in the Cline House, where Flannery and her mother lived before moving to Andalusia and which, I was told by a few people, “has enough boxes and crates and papers to spark a dozen dissertations.” The paintings were discovered in 2023 but kept under wraps by the estate, lest they detract (so goes the rumor) from the impact of O’Connor’s writing. Some academics were excited that the New York Times and New Yorker had come to Milledgeville to cover the unveiling, seemingly forgetting that the New Yorker (undoubtedly gleefully) published an essay that hurt her reputation to the point that Loyola University—that fine Catholic institution—removed O’Connor’s name from a residence hall.

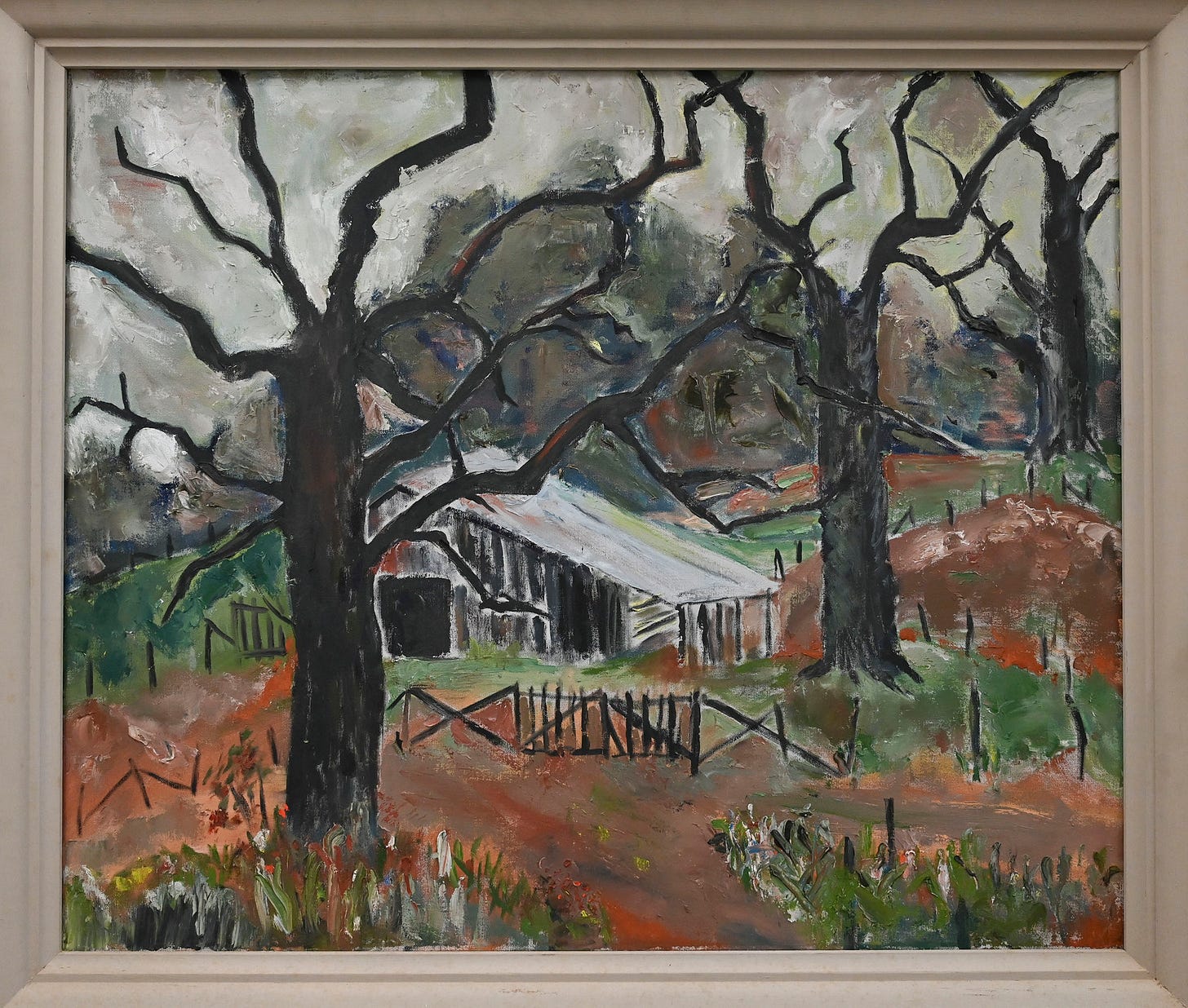

I could fill libraries with what I don’t know about painting, but I know enough to find O’Connor’s worth the time it takes to look at them. She famously justified her use of violence and the grotesque in her fiction with, “To the hard of hearing you shout, and to the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.” The paintings are neither large nor startling, at least not in the same way as her fiction. None of the paintings create anything like the overwhelming effects of the ends of her stories or novels—but we do see the love of detail and ability to capture what Emily Dickinson called “a certain Slant of light.” Scholar Robert Donahoo gave a lecture about how painting was a means for O’Connor to indulge in a creative impulse different from the work she completed at her desk: more of a hobby and a rest from her writing, yet still one in which her ability to see couldn’t be switched off. In his essay accompanying the catalogue, Donahoo states that the paintings prompt us to see “the deepest possible picture” of O’Connor. As with the cartoons, I am unsure if my admiration for O’Connor’s work (and character) clouds (or at least colors) my vision and judgment when I look at the paintings. Could I evaluate them as clinically and accurately as I assume Dave did when he appraised them? I learned from Hulga Hopewell, “Some people might enjoy drain water if they were told it was vodka,” but am confident saying that the paintings are certainly not drain water.

As I looked at the paintings and enjoyed hors d’œuvres, an older man approached me to let me know that the men’s room toilet was clogged. When I apologized and said that I didn’t work at the college, he told me I looked official and went to find someone else. Flannery would have appreciated that: you may think you’re special with your new blazer and your grant, but you’re no peacock. That pull down to earth happens to her characters all the time.

Mystery and Manuscripts

Many of O’Connor’s manuscripts are housed at the Russell Library at GCSU. I wasn’t working on anything in particular, but knew I had to read some of these. I was shown different indices to different collections and told I could read anything in them. There is a lot there: thousands of pages of juvenilia, things from high school, notes from her work on the literary magazine, and drafts and drafts of her fiction. This is what Jessica Hooten Wilson had to go through to assemble O’Connor’s unfinished third novel, Why Do the Heathen Rage? I knew I couldn’t go through all of it, so I decided to focus on The Violent Bear It Away, since it’s probably my favorite novel. I started in the middle and asked for a few folders. There seemed to be no logic to how they are catalogued: you might be given folder 185a (four pages of a scene), then 185b (one page of a different scene), then 185c (three pages of that first scene again, but with some alterations). It was great to see the actual typed manuscript pages, even if they were copies of the originals. I could see what she crossed out with xxxxxxxx and revised with a pen. When I asked about the policy regarding quoting these, I was told that I had to ask the attorney who handles this topic. I remembered well how careful the estate was when I wrote my book and the name of the contact as FS&G—Cynthia Fox—would flash in my head later when I read a scene in which Flannery gave the same name to a character.

I found dozens of profound sentences, long constructions, and whole scenes from the novel that never made their way into the final version. We all talk about killing our darlings, but there are darlings in these folders whose deaths most of us would never allow. I spent four mornings in the archives, reading in dumb amazement. All of the drafts reminded me of how I felt when I first heard Bob Dylan’s “Series of Dreams” and “Blind Willie McTell” and being shocked that he didn’t think these were good enough for an album. This opened a fascinating window into O’Connor’s creative process and raw talent. Reading Violent now, we see her authorial choices, such as Bishop’s disability and inability to speak, as aesthetically and inherently right—but the archives show that O’Connor didn’t have these characters or plots spring from her head like Athena from that of Zeus. Bishop began with a different name and voice; in one deleted scene, he composes a letter to his mother in Chicago and gives Rayber the kind of sass that his later version cannot. She wrote and revised to learn about the people she created. And since we only see the final versions, she makes it seem easy.

The archives also have O’Connor’s own library and a card catalogue of over seven hundred titles. Visitors can ask these books to be pulled and then flip through them to see if they contain any of O’Connor’s marginalia. Someone at another table struck gold with what she found in the margins of A Grief Observed so I tried my luck with her copies of the works of Henry James. In A Portrait of a Lady, Hawthorne, The American Scene, and a collection of his letters, I found not a mark. In a one-volume edition of his notebooks, I found sentences marked with squiggles in the margins, but nothing else. But in James’s essay on Guy de Maupassant, O’Connor put clear brackets around this passage:

In fine, his readers must be grateful to him for such a passage as that in which he remarks that whereas the public at large very legitimately says to a writer, “Console me, amuse me, terrify me, make me cry, make me dream, or make me think,” what the sincere critic says is, “Make me something fine in the form that shall suit you best, according to your temperament.” This seems to me to put into a nutshell the whole question of the different classes of fiction, concerning which there has recently been so much discourse. There are simply as many different kinds as there are persons practising the art, for if a picture, a tale, or a novel be a direct impression of life (and that surely constitutes its interest and value), the impression will vary according to the plate that takes it, the particular structure and mixture of the recipient.

I don’t know when she marked this passage, but what James argued in 1889 perfectly suits O’Connor: the impressions O’Connor offers, mediated by her singular temperament and photographic “plate,” are unique among the many different kinds of fiction. Some readers find these impressions not to their taste, but as O’Connor responded to a letter-writer who said this, “You weren’t supposed to eat them.”

I also managed to see the video of Galley Proof, a television show that aired in 1955 in which Harvey Breit of the NYT Book Review interviewed the thirty-year-old O’Connor about her work while holding a lit cigarette from which he never takes a drag and in which he speaks like a bad imitation of James Mason. (He’s what O’Connor would call an “intellectchual.”) He’s as unsuited to reading passages from “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” as Laurence Olivier would be to singing “Gee Officer Krupke” and behaves as if his grand idea—that O’Connor doesn’t write about southerners per se but all people—were revolutionary. Flannery looks like a downed pilot being asked to testify that she is being treated fairly by her captors: she later wrote in a letter, “I keep having a picture of my glacial glare being sent out over the nation onto millions of children who are waiting impatiently for The Batman to come on.” But she triumphs when asked if she would like to tell the viewers about what happens at the end of the story: “No,” she quickly says, “I certainly would not. I don’t think you can paraphrase a story like that. I think there’s only one way to tell it and that’s the way it is told in the story.” I had read the transcript of the show, but had never before seen O’Connor speak on film. As with Andalusia, what I saw fit perfectly with what I had imagined.

The Church and the Cemetery

O’Connor’s parents were married at Sacred Heart Church in 1922. After Flannery moved back permanently to Milledgeville, she and her mother attended mass there every day. To be a Catholic in Milledgeville was to be, if not a rara avis, at least an odd bird. (This idea must still hold today: when the priest spoke of welcoming back the prodigal son, he compared the son to those who might have left the Catholic church for “Baptist or other Protestant denominations”—a scenario I’ve never heard mentioned in hundreds of New Jersey homilies on this parable.) When Flannery was a parishioner, she was one of about fifty1 and the church suits what would have been a small congregation.

Sacred Heart is unlike any of the Catholic churches I’ve known in the northeast. There is no stained glass: the walls are white and unadorned, save for the carvings to show the Stations of the Cross. There are twelve pews on each side of the aisle and the simple altar is flanked by only two statues, one of the Blessed Mother and the other of Joseph. (There’s one of Christ pointing to the Sacred Heart in the back.) The organ is in the balcony and there are two confessionals against the back wall. A college kid was in the front, praying, so I sat near the back to take it in. The small scale of it made it appealing. I had been to the Cathedral Basilica of St. John the Baptist, Flannery’s church when she lived Savannah, which had an equally moving effect but with a source obviously different from this one. It’s like moving between a haiku and the Iliad—each does its work based on how we apprehend its scale.

There is something about entering a church in the middle of the day that shuts off the physical and other kinds of noises that bombard us all day. Even if one isn’t praying, nothing bad ever occurs as a result of sitting quietly for a few minutes.

One afternoon after 12:10 mass, I walked a mile to Memory Hill Cemetery, where O’Connor and her parents are buried. The cemetery was as silent as one should be. As I tried to recall what I saw on a map, I missed the graves the first time: many of them are flat, so you have to walk slowly and look down. Edward, Regina, and Flannery are buried in that order, on the edge of the property in the family plot next to the street. Flannery was buried there on August 4, 1964 at the age of 39. People had left pennies and coins in the shape of a cross, a few rosaries, some seashells, and pens—about a dozen different ones arranged in a circle. I thought about Hart Crane’s “At Melville’s Tomb” and W. H. Auden’s “In Memory of W. B. Yeats,” but that was all I could do toward thinking of something profound, like I felt I should: here I was at the grave of a writer whose work has affected me as much as any other, but all I could do was stand there and be still. I thought about my own parents’ graves and then shook off as best I could this memento mori moment. I hesitated as I left, thinking this could be the last time I would visit this cemetery and then staying still for another minute. I felt like a sliver of iron held between two magnets and it took me a few minutes to definitively leave.

A Movie and Some Music

Part of the week-long celebration included a screening of Ethan Hawke’s Wildcat, his biopic of O’Connor that he co-wrote and which stars his daughter, Maya, as Flannery. I had seen it before and written about it, but wanted to see it again in, of all places, the Russell Auditorium, the setting of O’Connor’s “A Late Encounter with the Enemy.” Before the film, two of its producers, Mary Welch Rogers and Joe Goodman, were interviewed by someone at the college. They talked a great deal about acquiring the rights to O’Connor’s work and how Goodman was able to get the rights to the complete canon because he established himself as a true believer. They had originally wanted to make a film of The Violent Bear It Away but that was put on hold to make Wildcat. The moderator polled the audience and we learned that about three-quarters of the people there had already seen the film and almost everyone there had read something by its subject. I enjoyed it even more this second time, especially since I sat alone in the balcony with no distractions. After the triumph of the tail feathers, everyone sat still throughout the credits: always a good sign that a film has done its job.

On Saturday, March 29, the final day of celebrations were marked at Andalusia with food trucks, a music festival, and free tours of the house. The staff had a shuttle running back and forth across the highway so that nobody had to play Frogger while trying to cross it and they could accommodate all the parking. I was there in time to see the first act: Matt McMillan, who played a set of acoustic songs and a few, impressively, on the banjo. There were only about ten of us listening at first, but it was still pretty cool. When he played John Hiatt’s “Crossing Muddy Waters” and Warren Zevon’s “Carmelita,” I grinned like a kid. As I stood near the house and waited for the next tour, a golf cart rolled up containing Mary Welch Rogers. I decided to tell her how much I enjoyed Wildcat and how glad I was that it was made. When I did, she smiled and shook my hand and told me that meant a lot to her. We immediately began chatting. I told her I had introduced the movie at a theater in Princeton and taken my wife, kids, and mother-in-law with me; she responded, “That’s wonderful! So—what did they think?” Eventually the tour began and we were all at the tail end of it; they could only take twenty people at a time.

After we had moved through the kitchen, I saw Mary walk back to a folding chair in the entrance room while the rest of the group kept going. I walked back and asked her if she was OK; she said yes and, “You’re such a gentleman.” Since I had seen the tour already and had a chance to talk to someone connected with Wildcat, I resumed our conversation and she immediately picked up the thread. She asked me what I did and where I was from; I noticed she didn’t have a Southern accent and learned she was from Missouri. When another tour group entered, we went out the back and I grabbed two chairs.

We talked about the making of the movie and the complaints of those who watched it only to catalogue its factual inaccuracies. “Telling a story is different from writing a biography,” she said, and we talked about the same phenomenon when “Bob Snobs” quibble about A Complete Unknown. I said I was surprised that O’Connor scholar Sarah Gordon said to The New Yorker that she “refused to see it” because Laura Linney (who plays Regina) made a mistake about where Flannery went to college, obviously (and simply) mistaking Iowa State for O’Connor’s undergraduate school rather than where she earned her M.F.A. When I said the idea isn’t to achieve one hundred-percent accuracy but to capture the spirit of the person, Mary said, “Exactly.” I said that I had a good time decoding all of the editing and rearranging, like when the Misfit in the beginning says the words of Mason Tarwater in Violent, or when Flannery reads “Parker’s Back” at Iowa—a story she wrote much later. “You have to tell a story,” Mary explained. “You aren’t writing a straight biography or a lecture.” When I expressed amazement that the estate gave Goodman permission to adapt all of O’Connor’s works, Mary said, “They know that Joe wants to do these things right.” As we spoke further about our favorite O’Connor works and lines, someone came over to thank her for making Wildcat. He was from Greenville, taught in West Virginia, and said he had to be here for the centennial. “See?” Mary said. “It’s incredible how Flanney brings all these people together.” He told us he made a peppermint pie, one of Flannery’s favorites, for his students; she reminded him that a little peppermint goes a long way.

Colin Cutler and his band took the stage that afternoon and played songs from Tarwater, a collection of songs inspired by O’Connor’s work that are (this is the kicker) very, very good, both as songs and as reactions to O’Connor. When I saw the LP in the Andalusia gift shop, I admit that I raised an eyebrow: what was this? The soundtrack to an imaginary film? A musical? The equivalent to Harry Potter fanfiction? But as soon as I found it on Spotify and played “Bad Man’s Easy,” I knew it was the real deal. Cutler has written, “I first encountered O’Connor in college, and was unsure what to make of her at first: I could tell she was good, but I wasn’t sure if I liked her. Eventually, I saw that she was putting her characters in difficult situations to see what they were made of—to tell human stories, with sparks of the divine burning through.” O’Connor certainly shows us what her characters are made of, which is the same stuff that we’re made of, too, whether or not we admit it. His songs about “Parker’s Back” and “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” are also terrific.

I met Colin the day before after the screening of Wildcat. He was there in the audience and the people I was with knew some people he was with—that kind of thing. For whatever reason, we all started talking not about O’Connor but about how many miles we had on our cars: he had a van that he just drove 160 miles from Savannah with a lot of miles on it; I forget how many. I said I had 193,000 on my Honda; another guy said he had over 200,000 on his Toyota. I had to say, “Nobody with a good car needs to be justified” and, in this town during this week, everyone got the joke.

Last Thoughts on the Pilgrimage

Earlier, I mentioned the passage by Henry James that O’Connor bracketed. There was another on the same page that she bracketed and which also suits her as well: “A writer is fortunate when his theory and his limitations so exactly correspond, when his curiosities may be appeased with such precision and promptitude.” O’Connor’s insights into fallen human beings finding unexpected grace corresponds exactly with her peculiar talent—what some might call a limitation, but which Flan-fans know is as sui generis as a peacock. And her curiosity was certainly appeased with precision; had she lived more than thirty-nine years, she could have satisfied her curiosity with even greater promptitude. But what she left us is inexhaustible.

Sarah Gordon, A Literary Guide to Flannery O’Connor’s Georgia, Univ. of Georgia Press, 2008, p. 52.

I watched the movie Wildcat which you spoke about. I thought it had interesting insights. I thought using Flannery as a character in her stories was way of saying that her story writing was part of her purgatorial process toward God. As if living through those stories was a way of breaking down her own idolatries. The stories are not about somebody else or not entirely, but actually about her own faults. So she’s telling on herself, not complaining about modernity. I also thought that even if she wasn’t actually in love with Robert Lowell, as the movie sort of indicates she probably did yearn for romantic love. So all of these things I was fine with. I just wasn’t 100% sure that it all turned into a really good movie. I’m going to rewatch it, but I’m not 100% sure about that.

Thank you for sharing this essay. As a writer from Georgia, graduate of UNC-Chapel Hill, I was brought up on Flannery O'Connor. She remains, along with William Faulkner and the more recent genius, Daniel Woodrell, one of my favorite writers, whose sentences I return to again and again, to learn how to write. I hit the article's link to The New Yorker essay, expecting to read something appalling, but I wasn't moved one way or the other. Perhaps it's worse to be called a racist than a chauvinist, and that's why we can shake a finger at Henry Miller, or Philip Roth, or Hemingway, or well, most male writers but don't feel the need to take their names off walls (as if any writer cared about a name on a wall.) Martin Luther King was the most important person in the history of the Untied States. He also beat his wife. Lately, I've been reading the stories Flannery O'Connor wrote for her graduate thesis at Iowa. I'm floored by her talent -- if anything is awry in the Nyer article, it's the lack of recognition for her genius. Anyway, in these early stories, she does not shy away from racism; that's primarily her topic. In at least one of them, she does inhabit the mind of a black character, despite her later claims. I guess I don't much care what my favorite fiction writers think about things (I love Hemingway and Nabokov) -- I just try not to read their biographies. In writing fiction, there's an alchemy at work -- maybe it's grace given to the drunk, the bigot, the racist. O'Connor would probably say that if you can do anything else, you should.