David Mamet's Caper

Heist

Here’s a post based on this week’s episode of Fifteen-Minute Film Fanatics and (at the end) a player that lets you listen to an ad-free version of the show. No spoilers in this one. The post and the podcast complement each other. The post usually is a deeper look at a single idea raised in the podcast. We take requests, so leave a comment below if there’s a film you’d like us to cover. We’ve done over three hundred episodes that you can find on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also listen to an ad-free version at the bottom. Please subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts and consider leaving a review on your platform of choice. Thanks.

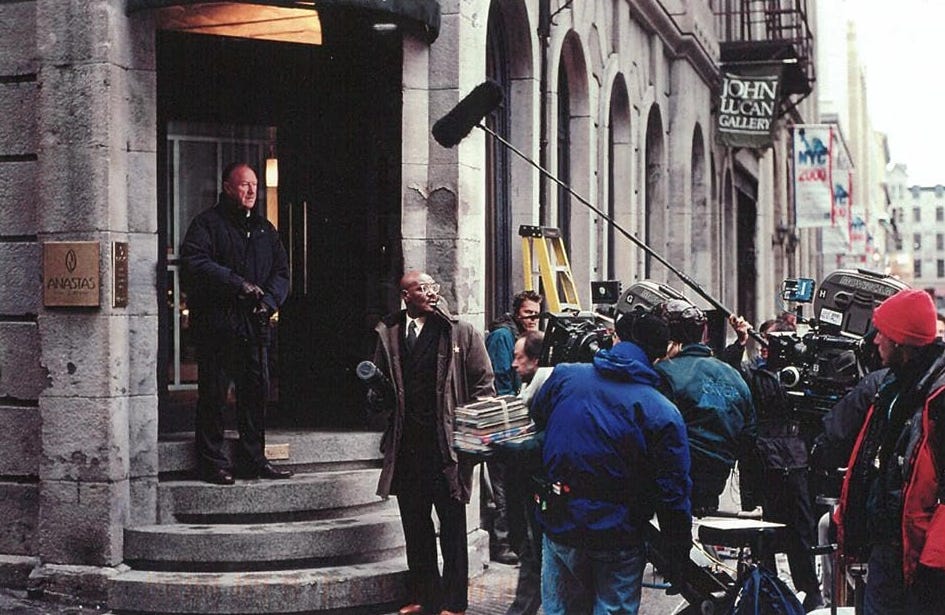

Thieves who plan and execute capers are like the people who make films about them. There needs to be a team and each member has a specific role that only they can execute. The complexity of the plan or script demands that the team reviews every move, so they meet in some form of rehearsal space (an empty set, an abandoned warehouse, the back room of a bar) and hash out the details of what will be their great performance. There are costumes, props, and special effects, all needed to follow the script and get the reward of loot or applause. But the production won’t be successful if anyone forgets their lines or botches a performance by overacting or not being sufficiently convincing. The thieves need to be as on their game as Olivier playing Hamlet or Tom Cruise hanging from a biplane; any error will risk the on-screen and off-screen audiences being unmoved and reminded that what they are seeing isn’t real. Whether you’re a character or an actor, the stakes are high and the height of those stakes makes for compelling viewing.

Heist (2001) is David Mamet’s celebration of the caper aesthetic. It constantly reminds the viewers that they are watching actors (Gene Hackman) pretending to be people (Joe Moore) who are, in turn, pretending to be other people (an FAA official, among others)—yet still offers a genuine emotional payoff in its final moments. It’s never cute but always cool.

A caper isn’t simply a robbery: there needs to be a degree of finesse and the actors and characters need to be smart. Some of them, of course, are a little smarter than the others, but that’s how the plot is propelled. When someone tells Joe Moore (Gene Hackman), “You’re a pretty smart fella,” Joe demurs and says he tries to imagine someone smarter than himself and thinks, “What would he do?” To those involved in a caper, brains are more important than bullets. The gang in Heat robbing the bank has a plan, but it’s not a caper; they’d use a Sherman tank if they could get one on the freeway. A caper must be a work of art: as Mickey Bergman (Danny DeVito) says of his scheme to rob gold bars from a Swiss cargo plane, “If I was a publisher I’d publish the plans.”

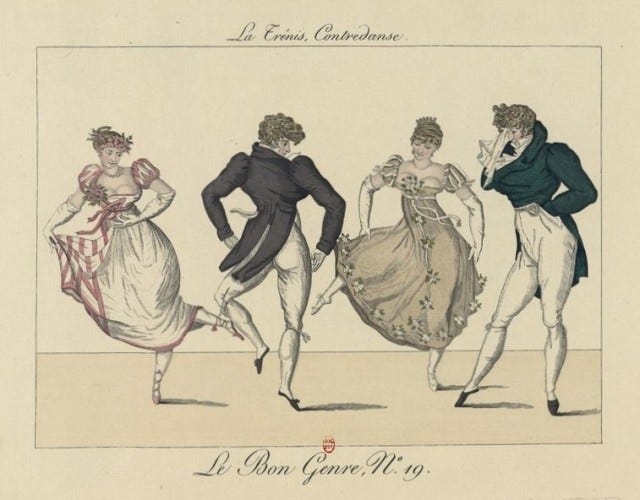

“Caper,” of course, also means “frolicsome dance” and the connection between dancing and stealing is one of those beautiful confluences of meaning found so often in English. The OED cites one of its first appearances in Robert Greene’s 1592 play A Quip for an Upstart Courtier as, “You master usher of the dancing school … stand upon your tricks and capers.” About six years later (1598), Shakespeare used the word figuratively in As You Like It, with the clown Touchstone observing, “We that are true lovers, run into strange capers.” By the eighteenth century, “cutting a caper” had taken the connotation of dancing with almost foolish and silly movements: thus Joseph Addison, in an early Spectator (1711), notes, “A Man may appear learned without talking Sentences; as in his ordinary Gesture he discovers he can dance, tho’ he does not cut Capers.” By the Victorian era, the word had also come to mean “game” or “racket,” as in a policeman quoted in an 1867 edition of the London Herald saying, “He’ll get five years penal for this little caper.” After another fifty years, the word traveled across the pond, with Americans using the term to denote an elaborately-planned robbery: Green’s Dictionary of Slang cites Dashiell Hammett as one of its first users in print, a 1925 story contains the line, “The princess can give you a fat cut of the profits in a busted caper.” In 1949, W. R. Burnett’s Asphalt Jungle (later adapted by John Huston) has a character vow, “When this caper’s over [...] I’m through with that hunky so-and-so.” Green notes of capers, “The supposed lack of violence in such enterprises lent them a somewhat ‘jokey’ air” and his irony-flagging quotation marks around “jokey” are well-used: capers are like jokes in that they are deliberately constructed to lead up to a payoff, although they are deadly serious to those involved.

The first scene of Heist—a caper involving a jewelry store—is as much of a dance sequence as found in the title number of Singin’ in the Rain. Every step is perfectly choreographed to give the illusion of spontaneity to anyone watching. There cannot be any missteps and the dancers need to be so focused that they disappear into their roles and make what they are doing seem perfectly plausible. (That both the jewelry store robbery and Gene Kelly’s song are interrupted by the police is another happy accident.) Caper films almost always detail the planning and personality-clashing leading up to the event, but Mamet gives us a taste of what’s to come by beginning with what the characters think is the end of their little play. That it’s a flop—Joe is “burned” by revealing his face to a security camera—is what propels the rest of the film and, of course, a bigger caper. It’s like a producer following a box-office disaster with a more expensive sequel.

The thieves in Heist pride their dedication to their craft and mock those who cannot work at their level, usually with the word “lame” used as a noun instead of an adjective. There are scenes in which the thieves are playing to avoid trouble or con someone else and they stay in character long after the trouble is avoided or the mark has left the scene; they commit so fully that they need a few beats to move back into their real selves. The dimwitted Jimmy Silk (Sam Rockwell) isn’t as good an actor as the rest of the crew and is scolded for his inability to stay in character. Yeats asked us how we could the dancer from the dance and in the world of the best caper-cutters, we can’t tell the criminal from the crime: the best of them move effortlessly into their roles with a fluidity only found among school children.

The casting is a way in which Mamet works like his characters: Joe Moore needs to be likable and Gene Hackman has to be believable. He needs partners as skilled as he is (Delroy Lindo, Ricky Jay) and a wife who fits the crew (Rebecca Pidgeon). Gene Hackman may not be the first actor that comes to mind when one thinks of “criminal cool,” but he’s perfect: he doesn’t cut a dashing figure but has a natural charisma that makes viewers in the film and in the theater believe him. His use of understatement is perfect: he never raises his voice. Rebecca Pidgeon is sexy but not a distracting supermodel—again, just the right touch. And if anyone has mastered the art of having just the right touch, it’s Ricky Jay. Only he could make getting himself hit by a car seem as effortless as one of his card tricks.

Being cool in a caper requires never having to tell yourself to be cool. When Joe’s wife tells Jimmy (Sam Rockwell), “Don’t smoke a cigarette” and he says, “Makes me look calm,” she asks, “What kind of person tries to look calm?” The thieves’ irony reinforces their cool because irony is a matter of intelligence, again a tool more valuable than a fake badge or lockpick set. Jimmy, a dolt, is only in the group because of his uncle (Danny DeVito) and has no sense of irony, two reasons why the other thieves resent him. When Jimmy asks if Joe will be cool under pressure, Pinky (Ricky Jay) tells him that Joe is so cool that when sheep go to bed, they count him; Jimmy doesn’t respond because he doesn’t get it. The thieves’ jokes are all understated, made without waiting for a reaction:

Joe: Anybody can get the goods. The hard part’s getting away.

Mickey: Uh-huh.

Joe: You plan a good enough getaway, you could steal Ebbets Field.

Mickey: Ebbets Field’s gone.

Joe: What did I tell you?

One plan is “cute as a Chinese baby” and another “cute as a pail full of kittens.” Joe says of his wife, “She could talk her way out of a sunburn”; when she is reminded that nobody lives forever, she replies, “Frank Sinatra gave it a shot.” When we think of clever things to say, we have a flash of pride and think of how to recreate these moments throughout the day so we can relive our small moments of wit.1 These people do it all day.

The cool of the caper is also reinforced in the dialogue. Since he won the Pulitzer for Glengarry Glen Ross in 1984, Mamet has been praised for his “realistic” dialogue, but that praise has always been inexact: his dialogue is great but far from realistic. The dialogue in Glengarry and elsewhere in Mametland does not sound like the conversations you have at work: if we interrupted each other all day as they do in that office, we’d never get anything done. (They also speak to each other with a level of honesty that we are afraid to use in our cubicles and staff lounges.) George V. Higgins is similarly praised, but again, the praise is inexact: real criminals are not as interesting to listen to as Eddie Coyle and Jackie Brown negotiating as they eat stale apple pie. Mamet’s dialogue is as “unrealistic” as Shakespeare’s. When readers first encounter Shakespeare and tell me, “People don’t talk like that,” I always reply, “I know. Isn’t that a shame?” Mamet’s dialogue is musical and interesting and exhilarating, but it’s not realistic. We don’t talk like Joe Moore and Pinky, which is one reason why we like to listen to them.

And this is why Mamet’s movie has a perfect title. Rather than “Love of Gold” or “That’s Why They Call it Money,” two punchlines from the film, Heist is the title that the characters would have given it. David Mamet is cool enough to know that.

You can listen to an ad-free version of the show here:

For the best literary treatment of this phenomenon, see James Joyce’s “Counterparts.”

I don't know the movie but am now sold. I love Mamet and Hackman. And also your word history of "caper." And also the bit about realistic dialogue at the end. I enjoyed the whole piece.

An underrated jewel of a movie. Mamet writes like Tarantino’s smarter, cooler, older brother. Thanks for the review.