The New York Times Book Review has revealed their 100 best books of the 21st century. I was alerted to it by Nick Hornby’s substack, in which he describes how he and 503 “novelists, nonfiction writers, poets, critics and other book lovers” gave their top-tens and the Times did the math.

The experience of reading this list is exactly like poring over the Sight and Sound poll of greatest films and finding most of John Carpenter’s choices surprisingly mainstream and some of Sofia Coppola’s downright silly. As in so many other arenas, those with whom we agree have good taste; those with whom we don’t make us roll our eyes. When I saw that one of my top-ten books was also on Hornby’s list, I nodded in approval, as if we had discussed it at length. Vanity, saith the preacher: all is vanity.

In His Girl Friday, Cary Grant complains that divorce “makes a man feel unwanted”; Rosalind Russell tells him, “But that’s what divorces are for.” We can’t complain if lists like these make us rail against sins of omission or get us worked up, because that’s what these lists are for. I am suspicious of people who can really choose their absolute favorite book or film–it’s like choosing your favorite color or number when you’re a child. Books do too many things for too many reasons: to say The Ambassadors is “better” than The Big Sleep is to cheapen the experience of both. They are literary apples and oranges and we read different books for different reasons. When Boswell complained that Richardson’s books were tedious, Johnson replied, “Why, Sir, if you were to read Richardson for the story, your impatience would be so much fretted that you would hang yourself.” In other words, that’s not what Clarissa is for.

I was lucky enough to be a juror for the Hollywood Reporter’s 100 Greatest Film Books of All Time, and, as I did there, had a good time agonizing over my choices. I wanted to include Best Friends by Thomas Berger (2003) and Dirty Money by Richard Stark (2008), not because they were these authors’ best, but because they were the final books of two people who have given me hours of reading pleasure. (Berger even corresponded with me for a decade.) Each of them wrote better books and I didn’t want to give them—even on my small-scale Substack!—pity votes for end-of-career performances or Lifetime Achievement Awards.

When we make lists like these, we act like we’re Olympic judges or in Henry VIII’s Star Chamber, despite our knowing that our lists won’t sway the culture toward our points-of-view. The purpose of making a list isn’t to urge your picks on other people, although that feeling is surely there, and if someone reads this list and then messages me that they liked some of the choices or picks up Time Out of Mind, I’ll be happy. The real point is to look back and revisit some of the highlights and, when reading other people’s lists, remind yourself of those books you keep meaning to read by authors people praise but whose work you haven’t yet encountered.

When I made the list, I didn’t focus on any genre—I just made a list of great books. Looking at it now, I’m surprised at how many biographies are on here, especially since people are now talking about the responsibility of biographers. I wasn’t surprised that there were only three works of fiction: a game I play in my head is to ask if I would really mind if new works of fiction were no longer published. I know, I know—heresy! I love fiction and have devoted much of my life to teaching it, but nothing by an Important New Author writing a Powerful First Novel ever seems to grab me. I think the last Really Big Event Book That Everyone Was Discussing that I read during its hubbub was The Corrections (2001). It ended up as #5 on the NYT list.

So here goes. This list could change tomorrow and I may want to amend it, but I won’t. Nor will I add “Honorable Mentions,” which suggests that these ten were added according to some complex rubric. The books are listed in order of publication, oldest first, with this final caveat: I am not doing any of them justice.

Theodore Dalrymple, Life at the Bottom: The Worldview that Makes the Underclass (2001). Theodore Dalrymple is the pseudonym of Anthony Michael Daniels, who worked as a physician and psychiatrist in sub-Saharan Africa and UK prisons. Life at the Bottom is a collection of essays in which he tells of his time trying to help people who have already ingested so many damaging ideas about themselves that they are almost beyond reach. The opening essay, “The Knife Went In,” takes that phrase from what a murderer told him about a stabbing for which he was imprisoned and examines the ways in which evading responsibility (or what people call “agency”) leads to objectively worse lives for everyone. He writes with conviction and erudition and begins with an epigraph from King Lear: “This the is the excellent foppery of the world, that when we are sick in fortune, often the surfeits of our own behavior, we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and stars.” It’s grim but so well-written with one great sentence after another that his work belongs to a very small genre: the page-turner essay.

Mark Harris, Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood (2008). There was a time when the Academy Awards were a big deal. They were never an ironclad gauge of quality (Going My Way beat Double Indemnity) but another means of industry self-promotion. (They are, like the one you are reading, another list that makes people nod or rend their garments.) Harris takes the five Best Picture nominees for 1967—Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Doctor Dolittle, In the Heat of the Night, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner—and tells the stories of their productions and receptions. We take Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate for granted, but they were incredibly controversial and tipped the balance away from older stars (like Hepburn and Tracy in Dinner) and genres (big-budget musicals). The parts about Doctor Dolittle remind us that what seems like a good idea at the time doesn’t always translate to box-office or artistic success.

Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs (2011). Jobs wasn’t a “computer wizard” or “tech guru.” He was a visionary who imagined that we could have a different relationship to technology. That relationship is a mixed bag of pros and cons, just like Jobs himself, who could be petulant, brilliant, kind, and brutally honest. I once taught this book in conjunction with Amadeus as a way to think about why we hold talented people to different sets of rules. The story of how Jobs used his reality distortion field to push other people to realize his vision is compelling and Isaacson keeps the perfect biographer’s balance. As Hamlet says of his father, “He was a man, take him for all in all.”

Ian Bell, Time Out of Mind: The Lives of Bob Dylan, Volume 2 (2013). I’ve been listening to and reading about Bob Dylan for a long time and recently had the chance to interview two curators of the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa—so I know my way around the Dylan bookshelf. Bell is the best of the biographers and this second volume of his treatment (“biography” is the wrong word) of Dylan is as good as the first, Once Upon a Time (1997). Beginning with 1975’s Blood on the Tracks and ending with 2013’s Tempest, Bell examines the career of Dylan (or “Dylan”) as American troubadour, artist, and icon. “His life,” Bell states, “had become a mixture of high art and low commerce, of thoughtful statements on the state of man and the modern world interspersed with textbook examples of the kind of behavior that gives stardom its disreputable name.”

The book is also a terrific study of the relationship between art and money. In Moby-Dick, Ishmael says, of being paid, “What will compare with it? The urbane activity with which a man receives money is really marvelous, considering that we so earnestly believe money to be the root of all earthly ills.” One of Bell’s themes is the shocking notion that Dylan likes being paid as much as anyone else. His Victoria’s Secret commercial, the Rolling Thunder Revue, the Never-Ending Tour, the Bootleg Series—even the selling of limited edition harmonicas—are all examined in light of Dylan’s urge to capitalism. Bell’s book ends before the 2014 Super Bowl Chrysler ad, but the effect is the same thing: anyone who groused that Dylan was somehow “betraying” his art in making a car ad seeks to speak from a position of innocence and cast the first stone. Nothing is left unsaid or unexamined. Bell died in 2015; I wish he were still writing so I could get his take on Rough and Rowdy Ways and the Great American Songbook albums.

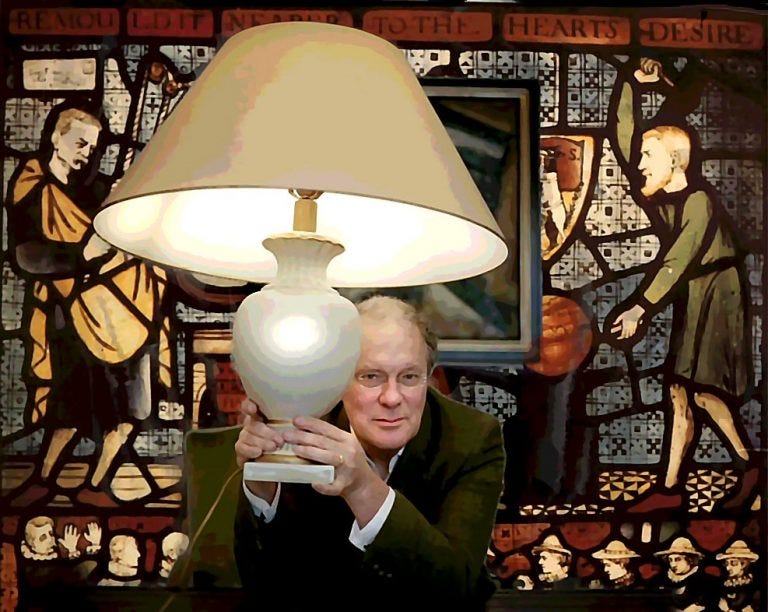

Frederick Barthelme, There Must Be Some Mistake (2014). Everyone knows about Donald Barthelme, the great short-story writer, which is how I stumbled upon his brother. After reading Bob the Gambler (1997) I began irritating my friends about why they had to read this, not because it captures all of human experience but because it does what the best novels do: puts the reader in the head of someone else. The interest is less in what happens (see Clarissa, above) than in the narrator’s deadpan observations on everything, from “Cardboard has a great smell. I like the crisp new boxes, ones that have never been used,” to “Fraught–that was the word I used, the only time in my life that I have ever used it.” But you also get passages like this:

I imagined her in Canada writing this letter reporting a disagreement that happened before his alleged suicide and noting, as she wrote, the irony of the gun going off and killing no one while he was preventing her suicide and then, presumably, using the same gun for his own suicide. I didn’t feel so good about that. I mean, who thinks about irony when they are hurting, when a crisis is right on top of them? Irony is a luxury for individuals in big houses and expensive dressing gowns, not people at the mercy of events.

How about that last sentence?

James Kaplan, Sinatra: The Chairman (2015). Sinatra may be the biographer's perfect subject, since he combined incredible talent with insecurities, fallibilities, and bad behavior. The book’s two epigraphs perfectly reflect the issues of the book: “Rap Mr. Sinatra if you want, buddy, but don't tell me that you’re not rapping him more out of envy than disapproval.” —Leo Durocher / “If you want to know a man, give him power.” —Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

The first is one readers and admirers of Sinatra must admit as they tut-tut over Frank’s bad behavior: shooting off his mouth at a casino, trashing hotel rooms, shamelessly toadying JFK. The second is the one that comes to mind when Kaplan details Sinatra’s lowest moments: smashing someone’s skull with a telephone, having Jackie Mason beaten up because of his Mia Farrow jokes, giving loyal friends the Sicilian cold shoulder for years at a time. It’s difficult to read this and then regard Sinatra as one did beforehand. As I’ve written in two recent pieces on The Hustler, talent is one thing but character is another. Many worse singers are better people, but they can’t give you chills when you hear them sing “In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning.” This book is 850 pages long and I wouldn’t cut a word. Kaplan knows his way around a sentence. (If you’re wondering what I think about the first volume of Kaplan’s biography, Frank: The Voice (2010), I haven’t yet read it.)

Harry Brandt, The Whites (2015). Harry Brandt is the pseudonym of novelist and screenwriter Richard Price, whose 1992 Clockers is the Les Miserables of Newark, New Jersey. Reading The Whites is like watching The Shield. There’s a compelling crime plot—two, actually—but they are almost beside the point. Price is great at recreating the stuff of everyday life: the groans, the frustrations, the sarcasm, the rolling of eyes—all of which make the cops believable and the reader’s relationship with them as tight as it is. There’s a scene where one of the characters argues with his wife and then makes up with her not with an awkward apology or confession, but by making small talk about TV—those kind of moments ring true and the book is filled with them.

Michael Benson, Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece (2018). When’s the last time you finished a book and said, “This is one of the best books I’ve ever read about anything?” This is one of them: one of the great books about artistic creation and I'm including A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in that list. Kubrick is popularly seen as a maniac, recluse, or jerk—here, he’s sometimes one or more of these but overall an intelligent and creative person struggling to articulate an idea and wanting to get it right for its own sake. Benson is great on everything: Kubrick and Clarke’s relationship, special effects, the story, the release, the impact—there’s not a single aspect that Benson has overlooked. I learned so much from this and I’m a 2001 know-it-all who still has my dogeared trade paperback of Jerome Agel’s 400-page 1970 anthology The Making of Kubrick’s 2001. I wish Congress could compel Benson to write another one on any other of Kubrick’s films. I know I'm being hyperbolic, but the book is that good.

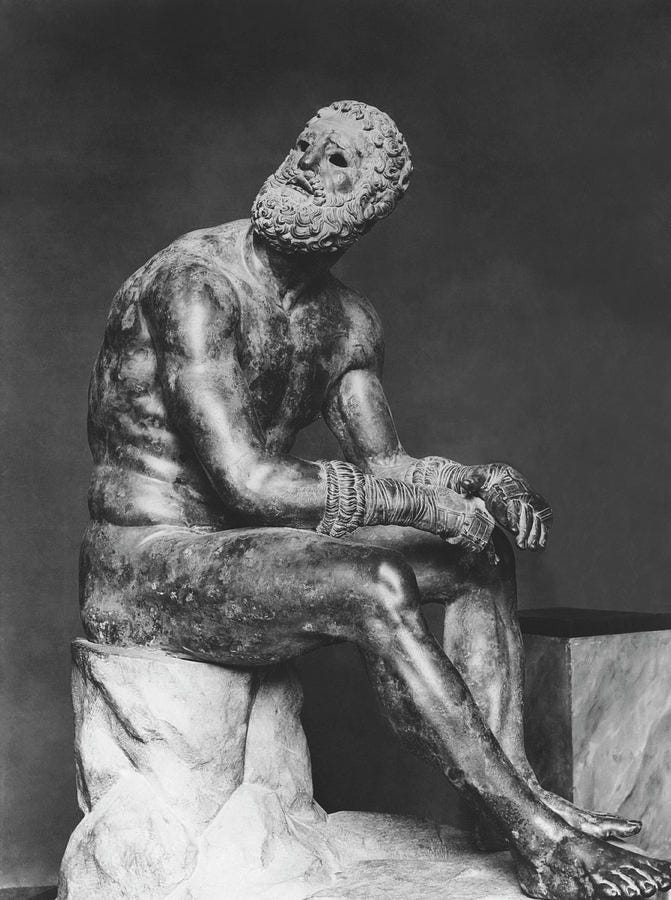

Thom Jones, Night Train: New and Selected Stories (2018). Whenever someone praised Tim O’Brien, a friend of mine would say that the writer that they really had to read was Thom Jones. I never really listened because I like Tim O’Brien and how many of us take the reading recommendations of our friends? But I came around: Thom Jones was a true original and there are stories here that are so good, such as “Pot Shack,” “Volcanoes from Hell,” and “Tarantula,” that I couldn’t believe it took me as long as it did to find them. His masterpiece, “The Pugilist at Rest,” is one of the best short stories ever written anywhere by anyone. People rightly praise Thom Jones for his Vietnam stories, but he didn’t do only Vietnam: “Silhouettes” and “I Want to Live” are as good as the ones about war.

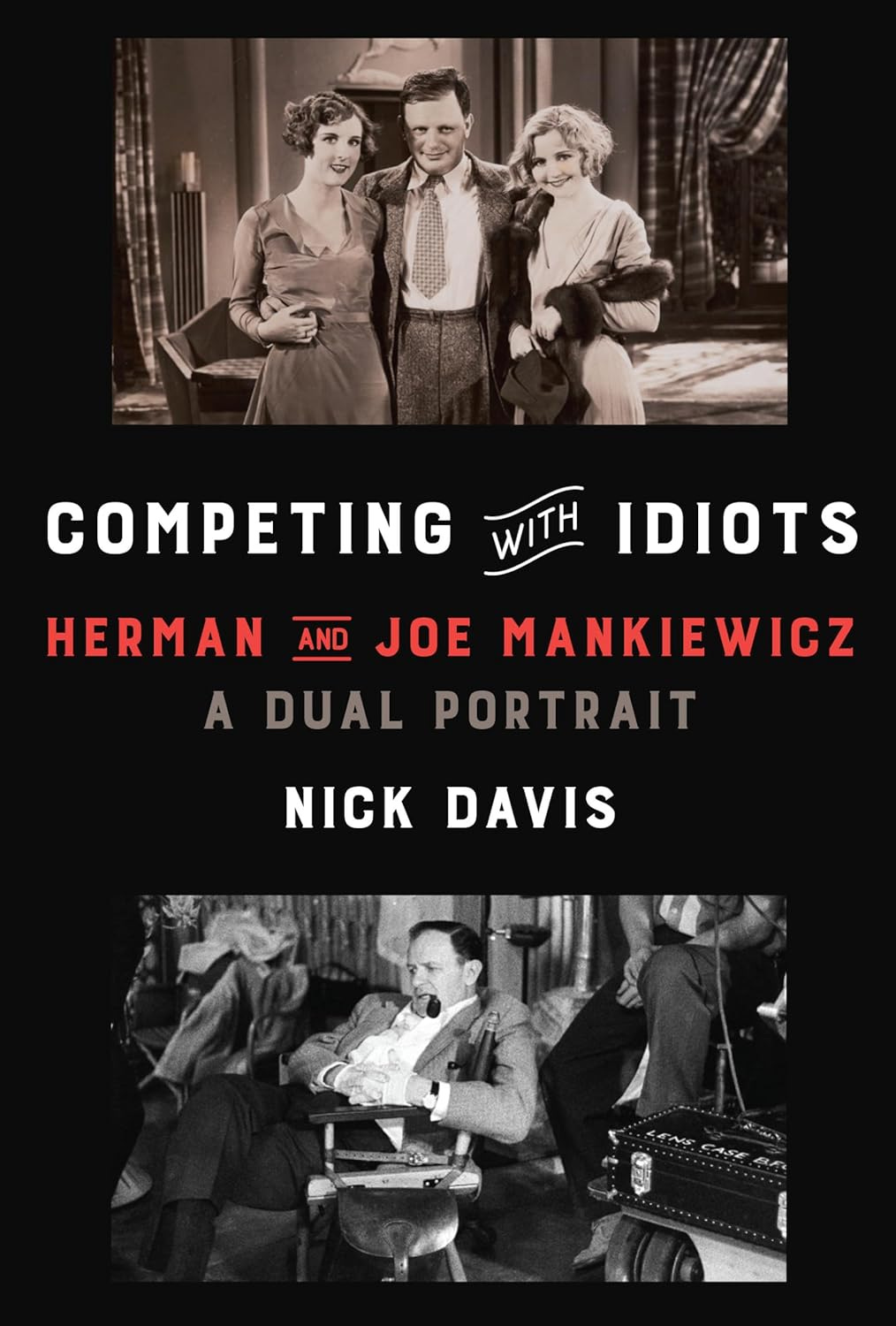

Nick Davis, Competing with Idiots: Herman and Joe Mankiewicz, a Dual Portrait (Knopf, 2021). I’ve interviewed the author and written about this book elsewhere on Pages and Frames. It’s an all-time favorite. Davis is the grandson of Herman and grand-nephew of Joe and has written one of the best books about families, talent, fame, and the degree to which we can truly know anybody. (That’s right: this sounds like the plot of the film that Herman co-wrote with Orson Welles.) Davis writes himself into the book, explaining that, as a kid, he was told repeatedly that Herman was funny and smart and wrote the greatest film ever made—and that his little brother, Joe, made the worst. The whole thing is done with great style. I read it twice, cover-to-cover, within the span of a year.

I’d love to hear some of your choices or reactions in the comments section.

You actually had two books that I read and enjoyed, the Mark Harris and the Kaplan. And I will be reading a few others on your list.

Thanks for including Thom Jones.