Without Enthusiasm

Spike Lee's Clockers

When I saw Eddington with my son, we had a long conversation on the ride home about why it didn’t work. He asked me if I was going to write about it or devote an episode of FMFF to it, but I told him no—talking about it in the car was one thing, but spending time recording or writing was another. Why go through the process of writing and recording and thinking about something one doesn’t enjoy? It would be like doing homework. While reading about why a film or book misses its mark can be as instructive and entertaining as why another one does, the motto of Pages and Frames is “Enthusiasm for books, film, and the places where they intersect,” as seen in this high-res graphic from the About page:

I like to read eviscerating reviews as much as anyone else, but they need to be written by someone with enough credibility and some kind of argument to make them more than just snark. When David Thomson reviewed Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master (2012), he began with a sentence I have not forgotten since I read it and which I’ve recalled while thinking of many films afterward, including Eddington:

WELL, AT LEAST IT’S PRETENTIOUS, and that’s a start in an age when too many films are hardly trying.

Like Roger Ebert and Anthony Lane, Thomson is interesting describing failures and actors he dislikes, even when I think he’s wrong, and there’s the comfort as one reads of feeling like they’re at the cool kids’ table. But the enduring value of critics is found in their admiration of quality, of pointing out what makes something work, of explaining how its effects are created, and of calling us over to their sides and saying, “Look at this.” Great critics help us read what they do when they read books we think we’ve exhausted; they help us see what they do when they watch great films. Ebert’s collection of one-star reviews, Your Movie Sucks, is amusing, but it doesn’t bear repeated readings like his three-volume The Great Movies.

Emerson said, “Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm,” and regular readers know that this is a Pages and Frames bedrock belief. The posts almost always urge readers to check out something (a film, book, songwriter, or even single song) because I want to share the joy I find in them. I like being turned on to things I never would have found (and had even foolishly dismissed); the best complement Mike and I can give each other at the end of a FMFF episode is, “Great pick.” We feel good as recommenders and in receiving the recommendations. It’s never a zero-sum game: the more we trust someone’s judgement, the more readily we’ll turn to another of their choices. Mike and I almost never differ on which movies to discuss, but on which ones we want to look at next. Enthusiasm only begets more of the same and the world of film and books really is an embarrassment of riches.

But this post is an exception to the only-enthusiasm rule because I think the film in question is a failure. Yet the film does reveal what happens when a director replaces what should his own enthusiasm for someone else’s work with the enthusiasm for telling his viewers what to think.

I recently reread Clockers, Richard Price’s 1992 novel, that sets Les Miserables among crack dealers and cops in the fictional city of Dempsey, NJ. It features everything readers love about the work of Price: the plotting, the characters so believable that you’d swear they are all based on hidden-camera footage, perfect dialogue, and a fundamental moral issue at its core. I enjoyed it in 1992 and even more thirty-three years later. I mentioned it in a recent post about the silliness of the genre “historical fiction,” arguing that if “historical fiction” aims to immerse the reader in the values, assumptions, and people of a past era, Clockers is as much a work of “historical fiction” as Wolf Hall.

Clockers has two protagonists. Ronald Dunham—almost always known by his street name, Strike—is a nineteen-year old dealer who sits on a bench outside the Roosevelt Houses all day, monitoring his crew and taking orders from Rodney Little, the neighborhood boss. Strike has almost constant pain from an ulcer that he tries to deaden with vanilla Yoo-Hoo. He wants to get off of the bench and move up in Rodney’s organization, although his heart is never really in it; when told to kill a clocker who has been stealing from Rodney, Strike can’t pull the trigger. He’s not an angel or the Carrie Nation of crack, but neither is he Tony Montoya. He doesn’t smoke, drink, or use any of his product. He’s resigned to his fate and his bench. He has safe houses with hidden cash and a plan to some day escape, but knows that he’ll be in Dempsey until he’s forced to live in a prison wagon or hearse.

Rocco Klein is a mid-40s detective on the verge of retirement. His job has become routine. He knows what he’s doing, but he has long ago abandoned the idea that he is keeping Dempsey safe. He will protect and serve, but goes home to his wife and toddler, exhausted. He opens his freezer, takes out a bottle of vodka, and takes what he calls “the Bryer’s pledge”: a swig long enough for him to read the side of the ice-cream box.

Strike works day and night in “the land of the two minute clock,” where nobody has any plans for the future further than 120 seconds. Rocco inches toward his pension and goes through the motions as much as any members of Strike’s crew. The cinderblock of a novel spans only three or so weeks, making the reader resemble the characters in their changing relationship to time: some days are exhaustive and long and others blur in the chaos of events. The structure of the novel invites the reader to regard both protagonists as clockers: the chapters alternate between Strike and Rocco, until they finally meet. The 600-page novel builds a world without the tiresome usual tricks of world building, like special vocabulary, characters who speak information aloud that they already know, or (even worse), maps and glossaries; Dempsey is as rich and real a place as Middle-earth, Narnia, or Tom Wolfe’s upper-east side. It’s also incredibly cinematic: there’s a murder, subplots, lots of dialogue spoken in cars en route to some sort of trouble, and the sense that Strike and Rocco are moving at 32 feet per second per second toward a collision, like Llwelyn Moss and Anton Chigurh or Vincent Hanna and Neil McCauley.

It should be a fantastic movie, but Spike Lee’s 1995 adaptation is a disaster. Or perhaps “disaster” is the wrong word, since it implies tremendous mistakes on a grand scale, the way in which people think of Cleopatra, Heaven’s Gate, or The Bonfire of the Vanities.1 The film of Clockers isn’t grand at all: despite all of the camerawork that calls constant attention to its director, it ultimately just sits there, looking and feeling like an after-school special about drugs, something in which Troy McClure would have starred as Rocco and that your principal would show during an assembly.

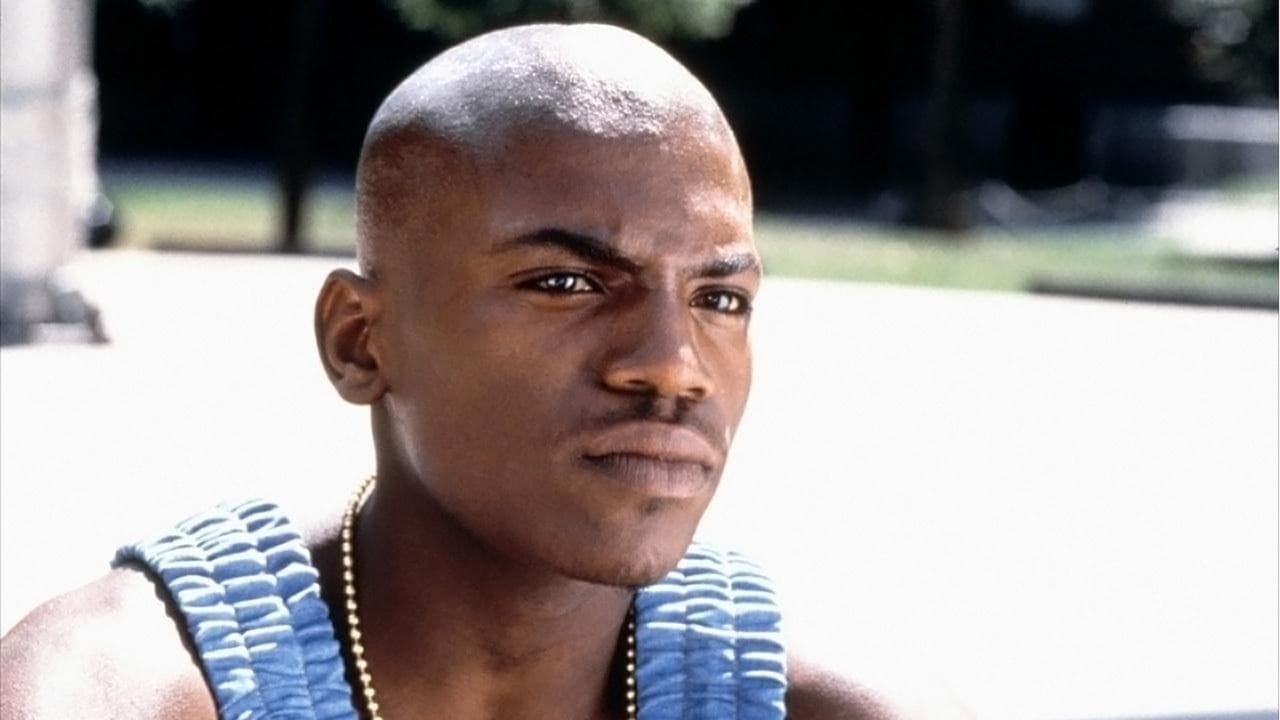

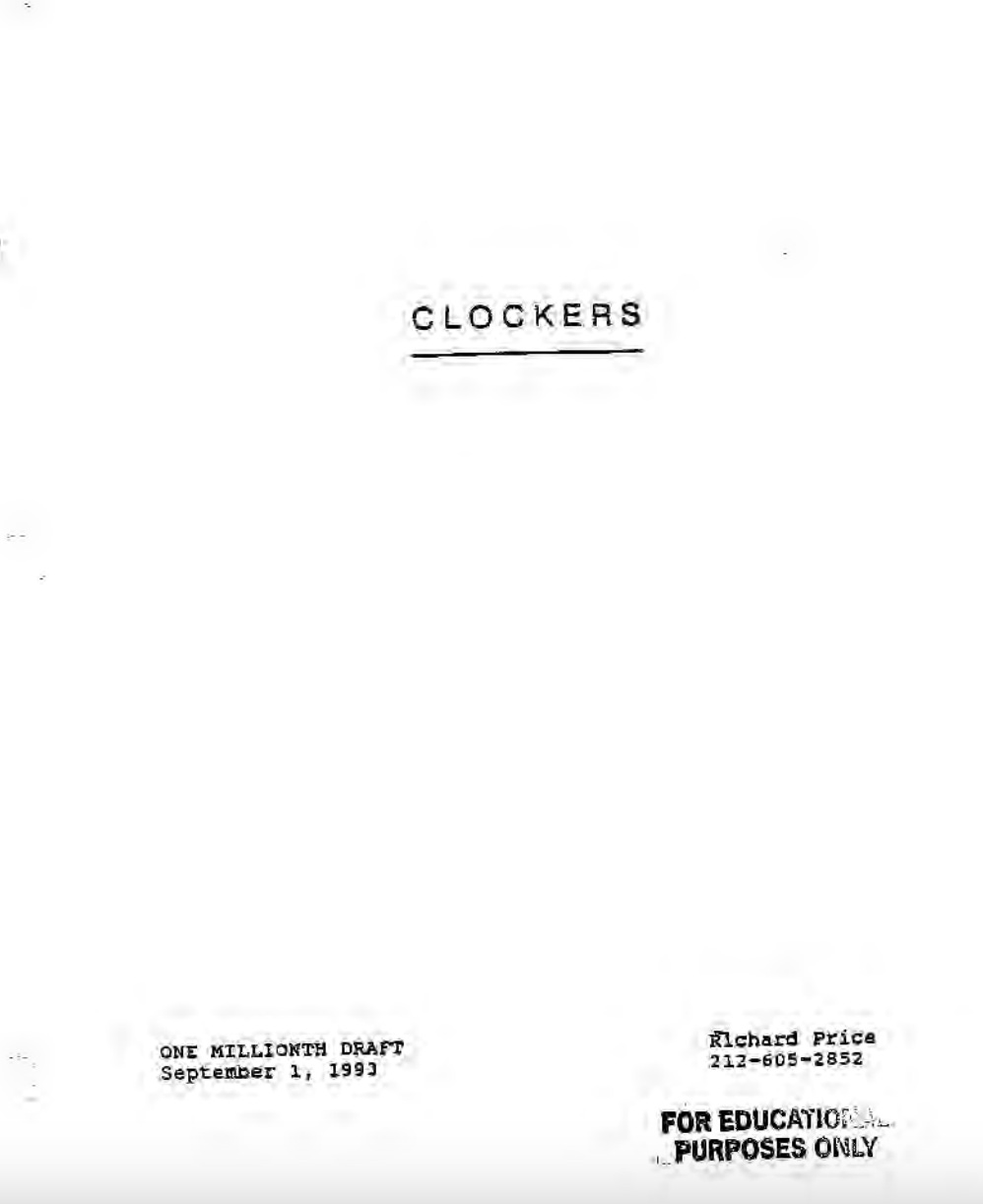

How could this have happened? Price was hired to adapt his own work, and knows his way around a screenplay as well as anybody. But when the initial director, Martin Scorsese, withdrew to make Casino, the project became a Spike Lee joint instead of enthusiasm for Richard Price’s novel. Lee saw Clockers as a way to undermine (or even stop) the wave of gangsta films that had been receiving a lot of play. He told the New York Times, “I was leery of directing in this black gangsta, hip-hop, shoot-’em-up genre.” That’s a noble cause, yet the novel is nothing like that; there’s more shoot-em-up material in a random episode of Dragnet. Lee also told Charlie Rose he was wary of the balance between Strike and Rocco that fuels the story. Robert De Niro was originally slated to play the cop, but once Scorsese left, so did the Strike / Rocco dynamic. “No disrespect for De Niro,” Lee said, “but when he left, I was able to change the focus.” The problem is that he changed the focus to himself instead of the characters.

There is nothing wrong with directors changing their source material; novels are not sacred texts and the canon is filled with examples of films that are far better than the novels upon which they are based, like Jaws, The Godfather—even Die Hard. Yet every move Lee makes as a director in Clockers is wrong; he turns a great, subtle human drama into a hamfisted editorial. The film is filled with garish close-ups and misplaced music at seemingly random moments, everyone is a caricature instead of a character, and the film yearns, from its opening montage to its ending, to make the deep statement that Drugs Are Bad.

The novel never gets pedantic because it doesn’t need to. Real art never does. In a 2008 interview, Price warned writers against expressing their indignation and turning their novels into op-eds:

If you try to write with outrage, it’s not gonna be as good. It’s not gonna be as telling. You don’t want to nudge people and say, “You should think this.” You don’t want to manipulate people into saying, “Can you believe….?” Just be faithful, and all the outrage will be there.

This is the exact opposite of what Lee did when adapting the novel. He removed the dual-protagonist structure, so that Rocco is simply a bully and Strike is a lamb. Harvey Keitel and Mekhi Phifer have nothing do do besides glare (Keitel) or grimace (Phifer). Lee knew that the novel is designed to let us dwell in the contradictions and ambiguities of these people, but he wasn’t interested in holding a mirror up to nature. In last week’s post, I wrote about how John Boorman’s Excalibur replicates the experience of reading Mallory, with all of his pre-modern style. Boorman gives you the story and spirit of Le Morte d’Arthur; Lee gives you half the story and none of the spirit.

Price’s reaction to the film shows Lee assuming that he had to have a hand in the final script in order to make it truly his:

Universal called and said, “How do you feel about giving it to Spike Lee?” and I’m thinking, “Sure, why not, who else are they gonna give it to?” So I met with Spike, and we talked a couple of times and then he went off to write. He said, “I read your scripts, and with all due respect, I direct what I write.” So he went off and he did his version of Clockers. My first reaction to it was—I was freaked out. Because it was Spike Lee’s Clockers. But over time I got to really, really like it. It should’ve been his Clockers; it’s his film, he’s the author. Books are never more than source material. It took me a while to arrive at that, but he’s a great visual artist. I’m nuts-and-bolts and he’s all about flourishes and kabuki stuff and kinte cloth and close-ups and zooms and stylized acting, this and that. And I’m sawing wood, one page at a time. I like it now, but it took me a couple of years.

It’s difficult to read this and not think that Price is being gracious. And he’s spot-on about his style (“nuts-and-bolts”) versus Lee’s (“flourishes” and “zooms”): the former pushes the reader’s attention away from the artist; the latter constantly reminds the viewer of the artist’s presence. Anyone reading Clockers forgets about Richard Price; anyone watching Clockers cannot stop thinking about Spike Lee.

In the same interview, Price ended the discussion with a shrug:

He did his thing. Stanley Kubrick massacred Lolita from Nabokov’s point of view, massacred The Shining from Stephen King’s point of view, massacred Eyes Wide Shut from Arthur Schnitzler’s point of view. But listen: the only thing a film owes to its source material is to capture the spirit, and everything else is fair game.

Yet the spirit of the novel is exactly what’s missing on screen. The messy process the reader has in forming relationships with Rocco and Strike is like the one for readers who pick up The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, The Stranger, or The Wings of the Dove, in which the title characters are many different, often contradictory things. (This also holds true for the most famous non-human title character in literature, who is many, many things to the characters, readers, and author.) A reader’s not being able to reduce characters to their lowest terms is a mark of the writer’s achievement.

Spike Lee wanted to make a statement instead of a movie, which may have flattered his ideas about his role as a director but which cannot create enduring art.

When asked her opinion of a contemporary novel, Flannery O’Connor said, “It is just propaganda and its being propaganda for the side of the angels only makes it worse. The novel is an art form and when you use it for anything other than art, you pervert it.” The same holds true for films. The enthusiasm has to be for the characters and not an agenda. If Lee had the enthusiasm for Strike and Rocco as people and not as points-of-view, Clockers could have been an interesting adaptation. But avoiding the Making of Statements has never been Lee’s strongest suit.

Strike and Rocco still surface in my brain every so often—but only because Richard Price didn’t tell me what to think of them. That’s the root of my enthusiasm for the book and disappointment with the film.

Two of these films’ reputations as disasters are undeserved. Cleopatra is far from the worst film ever made; after I finally saw it, I said it wasn’t even the worst film I had seen that month. The restored director’s cut of Heaven’s Gate is excellent. Bonfire is a disaster that echoes the very themes of Tom Wolfe’s novel.

I’m currently reading ‘Freedomland’, Price's next Dempsey novel after Clockers. from what I can tell from reviews, the film version looks to be another disasters for Price.

tough luck.

at least he got to write some of the greatest television episodes around with The Wire.

Price is my favorite writer and Clockers is his masterpiece. David Simon says it inspired The Wire. I support Spike Lee as a Nuyorican and usually never criticize him in mixed company, but he destroyed Clockers. Great take and essay, thanks.