“I’ll be sure to read it” is one of the white lies we tell each other all the time. Everyone who reads and has friends who read is sometimes in the crosshairs of a recommendation. “You’ve got to read this,” we seem to be told all the time and we say that we will, knowing as we are speaking that the odds of that happening are slim. We don’t doubt the sincerity or even the taste of the recommender, but crossing that bridge from nodding to holding the book in one’s hand happens less often than we pretend. We don’t lie out of malice; it’s simply a social convention. Samuel Johnson would have called this a mild form of “cant”:

You may talk as other people do: you may say to a man, ‘Sir, I am your most humble servant.’ You are not his most humble servant. You may say, ‘These are sad times; it is a melancholy thing to be reserved to such times.’ You don't mind the times. You tell a man, ‘I am sorry you had such bad weather the last day of your journey, and were so wet.’ You don't care six-pence whether he was wet or dry. You may talk in this manner; it is a mode of talking in society; but don't think foolishly.

We often say that we will read the books others recommended to grease the wheels of social intercourse. But to actually read them is a big step. Johnson advised it was fine to say one thing and think another, just as we say we’ll read one thing and instead read another.

A pledge to read something gets more complicated when we actually know the writer. Your cousin wrote an article, “The Economic Influence of the Developments in Shipbuilding Techniques, 1450-1485,”1 for The Journal of Nautical History and when he mentions this at Thanksgiving, you nod and say, “Really? I’ll have to check that out.” By the time the tryptophan hits, that ship has sailed. A friend of yours has been working on a self-published memoir for years; when it’s finally done, you buy it but don’t read it because you’ve heard the stories in it a thousand times. Instead, you leave it on the coffee table, offering the illusion that it might be picked up at any moment. And then there’s the situation most fraught with social difficulty: you know someone with a Substack. If that’s the case, the pressure to keep up with their posts can be greater than that facing Ethan Hunt as he tries to move between biplanes.

None of this non-reading is done with malice. We nod and say we’ll read the things because it’s a gesture of support and we want to be supportive people, even to near-strangers. We’re not monsters.

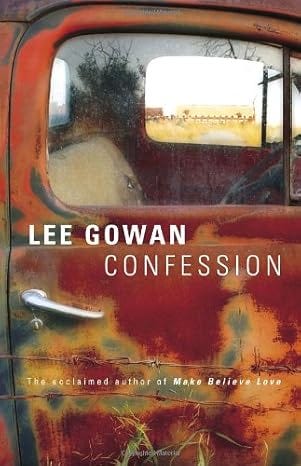

This past March, I found myself sitting next to Canadian novelist Lee Gowan in Milledgeville, Georgia. I was there for Flannery O’Connor’s centennial and a number of us who had been awarded travel grants by Georgia College and State University went to an exhibit of O’Connor’s paintings and then to dinner at Metropolis, a Mediterranean restaurant. As twenty of us made our way to a long table, I ended up on one end with Lee and his wife to my left. Naturally, we talked about where we lived, what we did, how we ended up in Milledgeville, and our favorite moments in O’Connor’s fiction. At some point, Lee mentioned that he taught creative writing at the University of Toronto; later he mentioned, wholly without bluster or what some would call “flexing,” that he was also a novelist. We had been talking so much and he seemed like such a solid guy that I told him I would read one of his books. He graciously said thanks, perhaps assuming I was making the kind of well-meaning pledge described above, and then we went back to talking about one-legged philosophers and one-armed con-men.

Back at the hotel, I looked up Lee on Amazon and Goodreads and found I had to choose from five titles if I were going to put my reading time where my mouth was. I had already taken a solemn vow to buy no new books this year and work on the pile I have, but this would be an acceptable exception; if Lee were pretentious or a drip, I would never have sought out his work. Besides, the only Canadian writer I had ever really read was Robertson Davies, who died thirty years ago. It wouldn’t hurt to read another from the Great White North. A day or two later, I ran into Lee and his wife at a screening of Wildcat and told him I had ordered Confession (2009), figuring its title fit the O’Connor mood. I didn’t read anything about it, but when his wife smiled and said, “Wait until you read that one!” I took from her reaction that the book is particularly intense. She wasn’t wrong: the novel is a first-person narrative about a young man who (as we learn in the opening pages) killed his father.

After I finished Confession, I thought about that dinner conversation. Gowan is clearly interested in the same themes as O’Connor; like many of her characters, the narrator, Dwight, tries to understand the workings of God and read what signs he can. “I’m even more confused about God than I am about women,” he says, and trying to dramatize that confusion is the author’s challenge. When a genuinely threatening figure dies of smoke inhalation after he fell asleep smoking in bed, Dwight wonders if this was some kind of divine plot twist:

God had dealt with him. Crushed him like a fly. God had either repaid his debt to me or chalked up one more debt against me that he’d expect me to repay in kind. I wasn’t sure which.

Other deaths—and what seems for a while like a miraculous act of healing—occur, making Dwight and the reader unsure if these are part of some divine meddling or dumb luck. “God has his secrets,” Dwight says. “I wish I could say that I’d come to know Him or He’d come to know me.” He doesn’t have a Milton to justify the ways of God to man. Gowan never tells the reader what to think about the issues that plague Dwight, who half-jokes that he wishes he were Russian and channels Dostoevsky in both his Karamazov-like story and search for meaning. The most he can do is write his story and then eventually burn each chapter as he composes the next one. It’s an act that reminded me of Paul Schrader’s great film First Reformed, in which Rev. Toller (Ethan Hawke) faces similar questions and fills a journal about them, knowing he will destroy it.

Confession could sit on the same shelf as Wise Blood or The Violent Bear it Away. There’s less ambiguity in O’Connor about the meaning of the violence and what God is communicating, since the fiction is undergirded by Catholic ideas. Here, Dwight wants something from God, some kind of answer, but his questions only lead to more questions. He’s a janitor who likes to keep things clean, but can’t scrub away his confusion.

I’m amazed by how a random seat at a long table could have led me to a book that I thoroughly enjoyed. It makes me wonder how many other books are out there that I haven't read but should—and I don't mean famous books I’ve been meaning to finish (Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, for example) but ones, like Confession, that were not even close to my radar. I had bought the book, published by Knopf Canada, from a used bookshop in the UK, and when it arrived, I found a stamp on the inside cover from the Anna Jarota Agency in Paris, along with a phone number in pencil. Imagine the number of coincidences that had to have occurred to get that book into my hands in the middle of New Jersey! How many other unfulfilled promises to read unknown books that I will enjoy are out there? To think that the pleasure of reading Confession relied on a random dinner and the good-natured conversation of its author makes me think that what I might call my taste, developed over decades of reading, is less serious and refined than it is. And that’s a thought as refreshing as the book that inspired it.

Those who know will recognize the title of Jim Dixon’s journal article in Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim. Unlike the writers mentioned here, Dixon would never urge his scholarship on another reader; he knows it’s dull and only exists to get him another line on his CV. Even he doesn’t want to read it.

I think in academic circles the book reading promise is more challenging to keep than in other white collar circles. The former has both a higher frequency and wider range of reasons for recommendations, including some being mere professional flexes. If a normie friend recommends a book (with a remotely applicable reason why they're recommending it) I have a very high fulfillment rate of my "I'll have to check that out" reply. Especially if it was something I previously considered, the rec turbocharges it up the reading list order.

Those books have gone through both a recommender's extensive filter of both 1) having outcompeted many other leisure time offerings to which people are deeply habituated and 2) reached a high certitude of well-received recommendation since it's so rare - and potentially embarrassing? - to make one. Even if the title does miss the mark for me, digesting it invariably enables a higher level of conversation next time with the recommender.

This is in stark contrast to TV series and film recommendations from normies. Those are often ill-considered, incessant and solipsistic. Worse, there is an unusually high expectation that you'll make the enormous time investment to abide the recommendation. Though I suspect the reverse holds true here: an academic's recommendation of one passes through similar alternative-choice-survival and potential embarrassment/disagreement filters.

100% relatable. Thanks for this heartfelt narrative Dan! Seems to be a bit more than a coincidence you two met.